Photographer Yang Xin takes free “funeral portraits” for elderly people in remote villages, and learns about their attitude to life and death

1

A photographer of the elderly

Yang Xin: Granny, are you on your own?

Granny: Yes, yes. My children all left for work.

Yang Xin: Give me a bigger smile, okay? You still have some teeth, right? Open your mouth a bit more and smile.

Granny: No teeth left, young lady.

Yang Xin: (laughs) Now that’s a sweet smile! One, two, three!

The above is a conversation between a photographer and an elderly lady, taking place in a remote rural village somewhere in the mountains of China.

Granny lives by herself. Her children have moved out of the village to seek work and a better future. This dialogue probably conveyed to you the relaxed and happy atmosphere of the photo shoot. In tune with the camera shutter, Granny grins and her smile is instantly frozen in a photo. However, there’s something you should know—the image itself isn’t for her to keep around.

Rather, it’s meant to be a ”funeral portrait (遗照)” to be hung over the coffin when Granny passes away, with copies displayed on the tombstone and in the homes of her descendants afterward.

Our narrator today is the photographer, Yang Xin. She was born in 1985. Over the past four years, Yang and her team have taken the funeral portraits of nearly 3,000 elderly villagers. What’s more, they do it free of charge.

Most of these grandpas and grannies are empty-nesters living in remote mountainous areas. Other than their ID card photo, this funeral portrait is the only picture of themselves many of them will take in their entire lives. This is Yang’s story:

2

What did Grandpa look like?

My name is Yang Xin, and I am from Shangluo city, in Shaanxi province. I am a tall girl, so that’s what everyone loves to call me—the tall chick. In fact, my user handle on Douyin (TikTok) is “Tall Chick Loves Photography (高妹爱摄影).” I have a day job as a photojournalist for a newspaper.

Being a photojournalist entails being constantly on the go. In my case, this often means going to the countryside, where I take pictures of elderly people in the mountains.

I remember this interview where I headed to a certain village. Once I got on the road, I found that a bridge that I was supposed to cross was missing. Villagers later told me that because of the transportation situation, when an elderly man who lived on the other side of the river passed away, it took many days for his body to be found. His family had to rush back with his remains and hold the funeral rites in a hurry.

What’s more, they told me that this old man lived his whole life without leaving anything behind—not even a single photo of himself. They shared this story with an apologetic tone, and the whole account of the incident moved me deeply at the time. When I was a child, I loved listening to my grandma’s stories about my grandpa. He died young and there was no picture of him at home, so I never knew what he looked like. My only impression of him came from my grandma’s stories.

As for Grandma herself, she lived with us for a while when I was in elementary school and junior high school. I would come back home from school in the afternoon, and if I had nothing else to do I’d sit on her bed, cover myself with her thick quilt, and listen to Grandma’s stories about her youth and about Grandpa.

Grandma said Grandpa had enjoyed great fame in our local community as a “barefoot doctor”—in those days, this referred to anyone who’d undergone basic medical training to become a healthcare provider in rural villages in China. They were farmers, folk healers, rural doctors, and recent middle or secondary school graduates who would go to different villages to provide basic healthcare, help with family planning, and treat common illnesses. Grandpa was a famous barefoot doctor in our area, said Grandma, because he toted a large block of tofu around, so that he could sell it when he went on his rounds. Sometimes, he’d be away from home for a day or two.

However, despite all those stories Grandma shared, she never told me what her late husband looked like. I tried to ask her, but she only said he was tall. She couldn’t describe anything else. I think she regretted no longer remembering what he looked like.

3

A smile in heaven

My family wasn’t well-off, so I didn’t take many pictures when I was growing up.

When I was 4 or 5 years old, my neighbor took a photo of me with a point-and-shoot camera. He later had the roll developed and gave my family the photo. In the picture—my very first ever—I am standing next to our old house with the other kids in my family with my head bowed down, wearing a pair of patched trousers.

When I see photo albums that other families kept for their children, stuffed full with baby pictures or milestones like their first birthday, I’ve always felt sorry for myself.

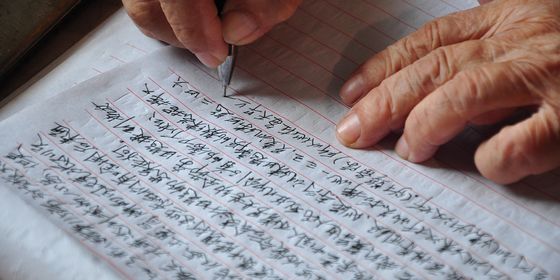

So when I took up photography as a major in college, maybe it was partially to make up for past regrets. Grandma was already very old, but I took countless pictures of her at that time with rolls of black-and-white film that I brought home from school—her little feet deformed by foot binding, her calloused and cracked hands bearing the signs of years of hard work, and her own solo portrait.

I remember directing her for that portrait. “Look at that bright sun. You go stand by the wall and I’ll take your portrait.”

Grandma smiled, brushed off the dirt and ashes from her clothes, and said, “All right, here I am. My baby’s gonna take my picture.”

She was grinning ear-to-ear in that photograph.

At that moment, I thought about how I was afraid that Grandma would be gone one day. When that day would come, I would no longer be able to document the imprint of life on her body or her smile. So, I really applied myself with those photographs.

Later, I developed that portrait by hand, scanned the negatives, and enlarged the photo to 16 inches. Finally, I made three prints, one for each of Grandma’s kids.

Grandma passed away less than two years after. My photo from that sunny day became her funeral portrait and was placed on her grave after the burial. It was then that I took another photograph of the tomb and posted it on my blog with the caption “A Smile in Heaven.”

4

“Why would people like us take photos?”

Once I started working as a photojournalist, I visited and photographed many elderly residents’ homes in the mountainous areas near Shangluo. Their poor living conditions inspired me to use my skills to their benefit.

That’s how I established the Shangluo Rainbow Public Welfare Center in 2017. There, I started running public welfare activities on weekends when I was not working. I mostly distributed free down jackets, wool knee pads, waist pads, and wool socks to impoverished elderly people over 65 years old in the region, hoping to help them survive the extreme winter cold in the mountains.

This process only got me acquainted with even more elderly people and their homes, which is how I came up with a rather shocking observation. Nowadays, mobile phones have made photography easily accessible to most everyone, but the majority of elders in the mountainous areas still didn’t have any photos of themselves. If anything, they regarded photography as a luxury.

It was then that I came up with this idea of taking their portraits, free of charge.

Once, I delivered clothes directly to a granny at home. When I walked in, the house was all smoky from an earthen stove burning with firewood. The stove was connected to the kang, a traditional heatable brick bed. On the cabinet directly opposite the entrance gate, there was a white piece of cardboard that was marked with Granny’s husband’s name.

There was an incense burner in front of the cardboard, and a pool of burnt incense butts in the burner signaled that sacrifices were regularly placed on that makeshift altar.

I asked the elderly woman, “How long has it been since your husband passed away?”

Over 10 years, she replied. I asked her whether she remembered what he looked like.

She smiled, clearly embarrassed, but remained silent—a likely sign that she did not remember.

I asked, “Granny, do you have any pictures of him?”

She simply replied, “Oh, why would people like us get their photos taken?”

Her words made me realize that photography was indeed nothing short of a luxury for her.

Shangluo is located in the south of Shaanxi, in the hinterland of the Qinling Mountains. According to a traditional saying, the land is 80 percent mountains, 10 percent water, and 10 percent farmland. In the villages, every home lies adjacent to the mountains. There are farmers’ markets where you can buy simple items, but there is no photo studio. You’d have to go into the city to get a standard 12-inch laser photo taken.

It takes 20 to 30 minutes to take a bus to the nearby towns. If you need to go farther into the city, you need to cross a couple mountains. There is only one bus a day.

Shangluo is a “labor-exporting” city that many young people will leave in order to seek work in the neighboring urban areas, perhaps even farther afield. Most of those who do stay behind are empty-nest seniors and some children left behind for their grandparents to raise. Mountain climbing and bus hopping is out of the question for elderly folks in their 70s and 80s

Very few elderly people in the mountains own a smart phone, and even those who do have one will only use the basic functions—shining the flashlight, listening to the radio, and receiving phone calls from their children.

The majority of these grannies and grandpas go without phones. They have few chances to get their pictures taken, and yet they are eager for any opportunity to do so.

5

“Young man, could you take my picture?”

One day, a friend of mine who specialized in landscape photography came to me with a special request. On one of his trips into the mountains, he’d met an elderly man who saw him holding a camera, who asked him, “Young man, could you take my picture? I’ll use it as my funeral portrait.”

However, my friend felt that funeral portraits were beyond his skill level, so he asked me to go back there with him.

Eventually, I found time to do just that. I found that this was a particularly remote area—no mobile phone signal—where some elderly people lived and grew vegetables that could survive in the alpine climate. I chatted with a grandpa as he watered his crop, and he told me that he was 68 years old, and that there were around 30 elderly people in the area.

Then, I disclosed our intentions. “Uncle, I’d like to propose something to you. I don’t mean any offense. We’re here to take funeral portraits for free, if you’d like us to, that is.”

At first, he didn’t seem to believe me. “Huh? You’re here to take my picture for free?”

After I emphasized over and over again that this was indeed the case, and that we would also frame the portrait and ship it back to him, equally free of charge, he finally laughed and said, “Ah, then that’s quite alright! Be my guest!”

He said that for elderly people who wanted to have their picture taken, there was no choice but go down the mountain and into the city. However, for those who were too old and frail to hop on the bus, let alone ride a motorcycle, this was impossible.

I also heard of folks who drove around in a van and, like myself, advertised themselves as free photographers for the mountain villagers. However, though they would indeed take a headshot for free, they would paste it on someone else’s body to complete the portrait. From then on, it was 10 yuan if you wanted it printed and an additional cost to have it framed—an average of 30 to 40 yuan for the most basic frames, to over 100 yuan for the fancier ones.

This grandpa had spent some money to have his picture framed and placed at home, only for the color to fade after only a short while.

And yet this sloppy job had been the elderly villagers’ only chance at getting their portrait taken. I followed directions that this grandpa gave me and eventually arrived at yet another uncle’s home where one of these makeshift portraits also hung. I wanted to check what it looked like.

He was having a meal, so his wife came into the room and took out a roll of paper from a large wooden cabinet. This uncle was reluctant to spend money on a photo frame, so he could only store his portrait in the bottom of his cabinet.

The woman carefully laid out the roll in front of me. This was, indeed, a cut-and-paste affair. The man’s headshot had been pasted on the body of a man clad in a suit, sitting on a luxurious European-style chair.

The auntie said in a hushed voice, “It’s not a good portrait. It doesn’t look anything like him.”

But, at least Uncle felt that he’d left his image behind, which was pretty neat.

He told me, “When those people come here to take pictures, you just gotta have one for yourself.”

What he meant is that elderly people feel they may depart this world at any given time. Therefore, they feel a responsibility to seize any chance they get to have their funeral picture taken before they go, as it’s one less thing for their children to worry about after their departure, and a keepsake for those they leave behind.

Before leaving this uncle’s house, I decided to hang a piece of red cloth on the wall of his house as a backdrop and shoot his portrait. Following my instructions, he sat at his own door and posed for me with a natural, relaxed smile, surrounded by his wife and neighbors.

6

Queuing for their last portrait

I was relieved to see how keen those elderly men were to have their portraits taken—it didn’t feel like a taboo subject. So, I decided to turn this into a regular project that I later called “Remembering our Elders.”

In 2018, we were able to successfully apply for a grant for this project, so we celebrated by holding our first ever group photo-taking event for elderly villagers.

Everything took place at the square in front of the village committee, and there was more to it than just photography—we offered free medical consultations, as well as gong and drum music and yangge dance performances. We’d feared that an event geared toward taking funeral pictures would be regarded as inauspicious and not many people would come.

However, it turned out we were worried for nothing.

We put up a backdrop on a frame in the square. Villagers had a choice of either the red side of the cloth or the blue side for their portrait. Once we had our setup ready, we had some old folks coming up to ask, “I heard from the village chief that you take pictures for free. Is that so?”

“Yes,” I would reply. “That’s right, I will take a 12-inch photo for you and send it back your way, all free of charge.”

Without fail, these grannies and grandpas would happily take out their ID card to sign up and queue for their turn.

We ended up taking over 300 portraits in one go that day, working nonstop from 9 in the morning to 2 in the afternoon. All those seniors lined up in a queue some 20 or 30 meters long. We feared that some would get jostled and fall down, so we had some volunteers come help us keep order.

Many of the elders went home and called their neighbors, and those neighbors called their relatives. Those with limited mobility or who lived too far away to come to us on their own had their younger relatives drive them on motorcycles, tricycles, and even wagons, all to come to us for their portrait.

The vast majority of them chose the red backdrop, as they thought it was a happy color.

7

Joyful scenes

Because of our initial fear that the villagers would be put off by the idea of taking pictures for their funeral, we referred to the portraits by the local euphemisms, like “seniors’ portraits” or even “old pictures.” However, I gradually came to realize that these grannies and grandpas were all well aware of the purpose of these photographs, and that death was not a taboo for them.

Our shoots were typically scenes of joy. We had volunteers in charge of several tasks—from spraying and combing our subjects’ messy hair, to straightening up the many layers of clothing that kept them warm, to dusting off their collars with small brushes.

We had this old guy who got all nervous immediately after sitting on the stool. He didn’t know where to put his hands—first he placed them on his legs, then he dropped them to his sides. I told him that he could let them hang down so that his shoulders would be flat, and he put so much effort into doing this that his fingers got all stiff.

Eventually, I had to reassure him. “Uncle, relax and don’t push yourself too hard. Taking your picture won’t hurt. What are you afraid of?”

This old man just smiled and said, “Well, I’ve never had my picture taken before.”

For some of them, it took a dozen attempts, sometimes even 20 tries, until I could finally get an image where they showed a natural expression.

Luckily, there would always be a jokey neighbor helping to liven up the atmosphere. “Hurry up and crack a smile for this young lady, you wrinkly coward. Or fine, don’t smile. She’ll just throw your picture away later.”

The subject, no longer nervous, would turn his head and retort. “Your picture’s not gonna get displayed, either. I’m gonna get them to throw it away.”

There they were, bantering with each other in this bright, lively atmosphere. Seeing so many fellow seniors getting their posthumous portrait taken at the scene, they probably thought, “Why, they’re all going to die, and at some point I’ll kick the bucket too, so why not have a good time?”

8

Living with your own coffin

Truth be told, local customs in Shangluo may have something to do with the attitude of local elderly villagers toward death. Here, death is a major life event that needs plenty of preparation in advance. Those who die past the age of 60 are traditionally considered to have lived to a ripe old age, and their funerals are meant to be festive occasions complete with firecrackers. The older the deceased, the greater the pomp.

Local elders past the age of 60 will also prepare their own coffin in advance, as well as their burial clothes. Once the coffin is ready, they’ll host a dinner party for their relatives and friends.

During my time in the mountains, I saw plenty of elderly folks who would live with their own coffins, covering them with plastic sheets and keeping them inside the house.

Once they’ve prepared everything for their afterlife, they may relax. When their time comes, villagers will say that their children and grandchildren displayed great filial piety, and that the deceased lived a happy life. If an elderly person dies suddenly without having made the proper arrangements, this will be seen as rushed and somewhat embarrassing.

9

The way they used to be

These elders rarely have specific requirements for their funeral portrait.

We do some post-processing on our pictures before sending them in batches for laser processing and photo frame mounting. This is done to achieve a natural-looking portrait, with most of the edits merely tuning the contrast and color scale. However, there are some special cases that will require more elaborate editing. For instance, some old folks have scars as a result of their frequent trips in the mountains to collect firewood, so we will do our best to allay those scars.

Some of them also have crooked mouths and eyes due to a stroke. In these cases, we always offer them to do some editing as well, “As long as you’re willing to let us touch up the picture, we will leave you all nice looking, just like you used to be.”

In fact, many of these old people were surprised to learn that photographs can be edited. Once, we sent the finished portrait to this old guy who was missing one eye. He was really happy to see the final result. Neighbors gathered around and praised the portrait, too. “Goodness, will you look at that! It looks every bit like your former self! Who would have guessed there’s such a technique!”

So here was this grandpa, being showered in praise and getting to see his former, “complete” self on his very own portrait—just like he used to be before his injury. I can only imagine the relief in his heart.

10

Bringing young people to the village

All I had originally wanted was to help elderly folks in these remote villages take their portraits, so that they can have one decent photo in their lifetime and make proper arrangements for their death. However, after coming into contact with so many elders, I realized that there was more to it than just a simple photograph.

Up in the mountains, everything’s so quiet. No noise. It’s only at mealtimes—so, at 10 in the morning and around 3 or 4 in the afternoon—that you’ll see a few grannies and grandpas chatting over their rice bowls under the village’s main tree or maybe at the entrance of someone’s yard. At some other times during the day, you’ll find them either laboring in their fields or toiling around the house: picking persimmons to dry as a sweet treat, and sun-drying herbs and plants that they will then use as traditional medicine.

Here in Shangluo, 60-year-olds are still very much strong pillars of the village labor force.

Once, when we were on picture-taking duty, we encountered a 68-year-old man whose face was scarred by the unmistakable signs of wet concrete splatter. We rushed to ask whether we could take his picture and found that he was, in fact, far from being retired from his job at the construction site. Village roads were still under construction, so this elderly uncle was still active himself.

During the persimmon harvest season, I also met an 80-year-old auntie climbing up a ladder to pick the fruit from the tree. I approached her saying, “Grandma, you’re much too old already for such a dangerous job. Why don’t you wait for your children to come back?”

She replied that the pandemic made it impossible for her children to come home, and they had to care for their own families, complete with her school-aged grandchildren. So, she was on her own, slowly picking as much fruit as she could. Someone would come along later to buy and pick up the harvest.

That’s just how those old folks are—they won’t stop for as long as they can move. They’re doing their best to try and lighten the burden on their adult children.

“So, do you miss your kids?” I asked the granny.

“When I do,” she replied, “I just look at them on the screen.”

That did surprise me. “Oh, so you know how to video-call?”

Not really. She waited for her children to call her; all she had to do was answer the call. That much she could handle.

In fact, the village livens up every time we go there, whether it’s to take portraits or deliver them. Many of these elders are thrilled to come out of their homes to meet us—young people who are about the same age as their grandchildren.

Once one of our photography sessions took place around lunchtime, and a volunteer went to the toilet behind the village committee. He was spotted by an old guy who was just finishing getting his portrait taken and immediately invited over for lunch, “Goodness, you must be hungry. Please, please, come to our house.”

So, the volunteers headed there for a homemade feast of jelly and baked cakes, which the grandpa had probably been looking forward to eating in the afternoon all by himself.

Volunteers at the shoots are always really patient with the villagers, always helping them to tidy up their clothes and chat with them about their daily lives. Some of these grannies and grandpas are actually pretty lonely. Some will say, “Why are you kids so nice? Gee, you’re more attentive to me than my own daughter.”

When you chat with these elderly folks, even a simple question about dinner or their usual crops can become true conversation starters. They’re really happy to be asked about their children and grandchildren. After all, it’s not like anyone usually cares.

Needless to say, they always linger for a while after we are done with the portraits for the day. They do so in order to invite us over for dinner at their homes. However, we always refuse out of fear of inconveniencing them. They’d serve us their own meal, or otherwise stuff our pockets with loads of walnuts that I knew for a fact that they’d originally planned to sell.

We did, however, accept their homemade cakes. Refusing those would have seemed standoffish and rude. So, we would take a piece of bread and share it between all of us. Boy, do they smile when they see you eating—the same satisfied grin that lit up my own grandma’s face when she watched me chomp on anything as a little girl, full of love and affection.

It’s not only the elderly villagers who benefit from these shoots. I feel both myself and our team of volunteers have healed through our interactions with them.

Once, one of the volunteers met an old lady who looked like her grandmother at a shoot. The woman stayed behind after our session had finished, so the volunteer ended up running up to her and asked, “Granny, you look like my grandma. May I hug you?”

The elderly lady was more than happy to oblige. She took our volunteer’s hand and replied, “Why, you look like my granddaughter yourself, young lady.”

Later, the volunteer confided to me that she dearly missed her late grandma, who had raised her. We were all in tears as we watched her press her cheek against the old woman’s own.

These old people may lead a humble life in their mountain village, but their optimism and open-mindedness are nothing short of educational for us all. By getting along with them, it was soon apparent to us that life really is precious. When you think about the way these grandpas and grannies go through their life, can you really get all riled up over trivial problems in your day-to-day?

11

An exhibition of funeral portraits

Delivering the portraits to their elderly owners is just as important as the shoot itself.

We lacked experience when we first started doing this, so at first we pooled portraits from three villages together before sending them out in batches. All in all, it took us some three or four months after the actual shoot to deliver the portraits. It was only when we sent them out that we learned that four of these villagers actually passed away before receiving their portraits.

After that, we decided to do our utmost to send the finished photos to the elderly villagers within a month. With every delivery, we would hold an exhibition of the portraits from each the village.

In these exhibitions, we string together with wire on a display rack hundreds of 12-inch funeral portraits. These grannies and grandpas gather together, surrounded by their own bright, smiling faces upon the red backdrop,

I’m not exaggerating when I say that this is often their last chance to meet one another in their lives, for some of the eldest villagers are already in their 70s or 80s. Nobody knows for certain how much longer they have. So, we hope to present them with a chance to have some fun together. They compare their photos to see whose looks the best, just as if they were having a small tea party, and their usually quiet village will suddenly liven up.

12

An old man singing his thanks

Whenever we hold these exhibitions, the villagers will always thank us and apologize for troubling us.

I specially remember this one grandpa with a birthmark on his face. He’d already picked up his photo and was starting to leave when he turned back and told me, “You’re all so nice, you traveled this far just to take our portraits and then deliver them all to us without ever charging us. I don’t have anything to thank you with, so I will sing some Qinqiang (Shaanxi) opera for all of you.”

With this said, he stood in the middle of the small square and began to sing his heart out.

It was a cloudy and windy day, and this grandpa belted his rendition of Qinqiang opera while holding his portrait in his arms. Without even noticing, a certain heaviness seized my heart at the sight of this scene.

He apologized once he was done. “It’s not like I’m any good, anyway. But, I just wanted to show my gratitude.”

13

All alone in the world

Once, I also saw this old guy wandering back and forth in front of his photo. I went up to him and asked, “Do you like it, Uncle?”

The photograph was fine, he replied. “Well then”, I said, “take it home with you, I’m sure your children will be happy to see your portrait.”

I sure hadn’t anticipated the tears in that uncle’s eyes as I spoke. Then, the village cadre told me that this elderly man did not have any family, and lived on government welfare provided to elders who are all alone in the world. I ended up chasing the still-tearful man down to persuade him to at least take his portrait home, if only for his own sake. “Uncle! Uncle, at the end of the day we all have to live for ourselves. Take your portrait home, please. If it brings you even some happiness whenever you look at it, then that’ll be good enough already!”

That’s the only time I ever did see one of our models take their portrait home in tears. And, that’s the last time I ever ventured to tell any of them that their children would be happy to see their portrait without waiting for them to share their family situation first.

14

A broken taboo

Let’s go back to that uncle I mentioned before—the one who paid to get a portrait of his head edited onto someone else’s body. If you remember, he lived atop a relatively remote mountain, so once we got his portrait done and framed, we decided to deliver it to his door.

That was a day to remember. Grandpa looked a little embarrassed as we all watched him fish out a key from inside a shoe at the entrance of his house. Then, once he opened the door, he went immediately to the big wooden cabinet facing the door and placed his portrait on top. Stuck to the back of that cabinet was a roll of paper that seemed like a family lineage. I figured the cabinet was meant to house the family’s ancestors, so any picture should only have gone up there once the person had passed. I didn’t expect this old guy to place his portrait there himself.

At first, I was startled and hurried over, saying “Uncle, please don’t do that. Your kids won’t be happy when they come home and see your portrait up there before it’s your time.”

But Uncle didn’t see it that way. He just liked his portrait. Ever since then, we were all the more determined to continue this project—it became apparent to us just how badly our rural elders needed it.

You see, a photo is not just a thin sheet of printed paper, but also a memento concentrating an elderly person’s lifetime of memories. They do not want to be forgotten, and they especially want to continue watching over the children they lovingly raised for decades. These grannies and grandpas look at their portraits as a chance to freeze their best self for generations to come, so their descendants can remember them and pay homage to them on special occasions such as Chinese New Year.

But I am just as blessed that I’m able to shoot their portraits. I wouldn’t call it a sense of accomplishment, but I do feel that I’ve finally done something in my life that I truly like, and that others get to enjoy too.

15

More than just a photo

When I go on my photography trips, I usually take some other footage to upload to Douyin. Initially, I would just post whatever I felt like, and it would go largely unnoticed. However, last April one of my clips generated quite a buzz in the media.

Following our sudden viral turn, netizens from all over China poured into the comments section. Some shared stories about their own grannies and grandpas. Some actually invited us to bring “Remembering Our Elders” to their hometowns.

Nowadays, whenever we livestream on Douyin, I’ll feature lots of images of our photography sites in the background. Once I got a message from this excited follower, “I just spotted my parents there!” He was actually from Shangluo, though he’d moved away for work. By the time this follower finally got the chance to go back home for a visit, he was thrilled to see both photographs, even though sadly his parents’ health had declined already since their photographs were taken. But in the photo frame, they would always look strong and healthy, long after they were gone—we’d captured them just in time. So this follower was really grateful. “Seriously, thank you so much!”

Honestly, we feel thankful ourselves. In a way, we are able to help these rural youths with their filial duties while they’re away from home and working hard.

As for ourselves, the biggest hurdle we’re facing right now is actually fairly unexciting. Our financial resources are very limited; after all, we’re but a small, volunteer-run organization hailing from Shangluo, deep in the mountains of Shaanxi. I’m a reporter myself, so I am often out on duty. Some people on my team are stay-at-home parents, and some are even self-employed. We’re all taking time out of our busy lives to participate in these public welfare activities. We need to secure the kind of support that will allow us to keep on going with our photography sessions and charity work without worries. However, there’s only so much we can do on our own. Therefore, we are forced to rely on bigger partners such as the Douyin Charity Foundation and their campaigns.

Over the last four years, we have only photographed around 3,000 elderly people in these remote rural areas—merely a drop in the bucket. At the very least, we feel that we must go on offering our photography services to our elders in Shangluo. But really, we hope to spread our reach further. We also aspire to come up with unified standards for our portraits’ quality and processing technology, among other things.

Ultimately, we hope to present our elders with photography that will not fade as time goes by.

All photographs provided by Yang Xin (杨鑫)

Podcast episode produced by Jie Yi (洁漪)