Peek inside the workshop of a Chinese artisan, who is trying to keep alive the centuries-old craft of making “heads” for traditional lion dance

Bamboo and silk strips cover every surface in He Yubin’s workshop, and there’s not a computer in sight. But still the 37-year-old jokes that he’s an expert in “3D modeling.” “I’m just using a human brain instead of an electronic brain,” says the artisan, who makes the heads of the “dancing lions” seen at traditional Chinese festivals around the world.

The skeleton of the lion’s head alone takes two or three days for an experienced artisan to make. Hundreds of bamboo strips and over 1,300 steps are involved in this centuries-old craft. He Yubin is the “sixth generation” inheritor of this craft, and his family runs the largest manufacturer of lion dance costumes (or so he claims) in the city of Foshan in southern China.

As the folk saying goes, “Where there are Chinese, there is lion dancing.” The performance, which dates back at least to the Tang dynasty (618 – 907), is often seen during holidays or other festive occasions—such as a business opening or family moving to a new home—as lions are believed to be auspicious animals able to protect people against evil and harm. In the Song dynasty (960 – 1127), the performance was brought by migrants to the south and integrated with local forms of martial arts to create the Southern style of lion dance, also known as xingshi (醒狮, “awaking lion”).

Lion-dancing has since traveled with Chinese emigrants all over the world, and can be seen in Chinatowns and traditional Chinese holidays on every continent. Over 50 teams from more than 20 countries and regions participated in the International Dragon and Lion Dance Virtual Competition in 2022. Many regions of China have their own style of lion dance and costume, and the Foshan style, based in the city of the same name in Guangdong province, is one of the most exacting and renowned.

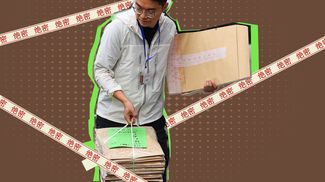

The four major parts of traditional Foshan lion-making is abbreviated as “bind, paper, paint, and decorate (扎, 扑, 写, 装).” After binding the skeleton using bamboo strips, the artisan covers the structure with starch paste, three to six layers of paper, and one layer of gauze or silk, all cut into small strips.

Once the papered skeleton is dry, artisans like He paint it in a rainbow of colors using a Chinese writing brush, often adding images of historical characters from Cantonese opera, such as Three Kingdoms heroes Liu Bei (刘备), Guan Yu (关羽), and Zhang Fei (张飞). The characters are color-coded to showcase their different personalities: white and yellow indicate Liu’s royal lineage, calm, and wisdom; red for Guan’s chivalry and integrity; and black for Zhang’s might and combativeness. Lastly, he adds the lion’s movable lower jaw, eyelashes, ears, and other decorations.

Not a single part of this process is automated, and it takes at least a week. A typical lion head weighs less than 5 kilograms, but can sustain over 10 times its weight without changing its shape. According to a report last March by Nanfang (Southern) Daily, a state-run local newspaper, there are over 2,700 lion dance troupes just in Nanhai district of Foshan, a township commonly believed to be the birthplace of Southern lion dance. Contests and festive celebrations aside, these troupes also perform at commercial events and local tourist sites.

Though the number of lion head orders, especially international orders, has increased over the last decade, He’s workshop has had difficulty in getting enough hands, especially from young people. “The craft [of making lion heads] is more at risk of being lost than the lion dance itself,” he says, explaining that unlike “the quick sense of accomplishment” one can get from mastering a movement in lion dance, young people are “not patient enough” to work around 10 hours a day (during peak periods) to make the costume, or to take a decade to master the skills. The salary, ranging from around 3,000 yuan to 8,000 yuan a month, is not attractive to them, either.

Still, He is positive that the craft “won’t disappear.” Government subsidies, and the efforts of artisans like him, who work with schools and companies to teach their skills to students of all ages, will hopefully keep the head on China’s dancing lions for generations to come.

Photography by Tan Yunfei (谭云飞)