Author Tang Fei spins a yarn about alien sheep and intergalactic ties that bind

1

Quite a sense of relief. The jet of water cut a full arc through the air, landed in front of her feet, and rushed merrily down into the ground. Like a small shiny snake, it quickly burrowed into the sand, leaving only a wet mark behind.

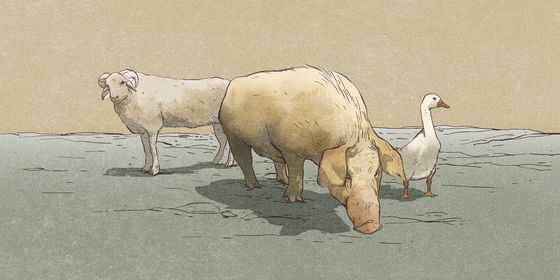

Yah’din gave a long, comfortable sigh and felt no hurry to get up. The wind had died down. Quiet. It was a fine day—up above, a sky lucent like egg white, and down below, a land of endlessly undulating red sand. Between the sky and the sand, there was Yah’din, squatting in the shade of a sandstone cliff with her bum out. Her bum felt cold; it was as bare and natural as the rocks on the ground. She heard movement behind her, a rapid rustle, like the sound of winds rushing through the tops of bushes. Yah’din pulled up her pants and looked toward the noise—it was her sheep. A red ball of curly wool stumbled and wobbled toward her, stretching out its head, looking all focused and serious.

Yah’din laughed, ran toward the sheep, and scooped it up. The sheep was exhausted. It gave her face a rub with the wet tip of its black nose, and then just laid close to her chest, collapsing into a small mass of softness and warmth, as if there were no bones in its body. Yah’din stroked its back again and again, repeating over and over “Ah, Sheep. Ah, Sheep.” Her voice rose and fell with the heaving of the small body in her arms, or maybe it was the small body that rose and fell with the ebb and flow of her voice. Anyway, one naturally matched the other, as Yah’din’s voice traveled across the vast wilderness. Yah’din’s Ma said she pampered the sheep so much that it became too needy and could never be separated from people.

Yah’din buried her face in the sheep’s wiry wool. A hot leathery smell immediately rose to her face, and suddenly she became wide awake. “You are the last one. Be as needy as you like,” Yah’din whispered next to the sheep’s head.

There was only this one sheep left in all Longgu’er. People all said that when Great Granny was a girl, she could sit in the yurt and watch the sheep herders lead hundreds of sheep rushing by. Even when they were far away, you could already feel the ground shake beneath you and the furniture rattle like crazy. Like rumbling thunder that rolled closer and closer, thousands of hooves the size of bowls stamped across the ground, kicking up a sandstorm, as if a giant red river came rushing from the sky. Whenever Yah’din thought about that spectacle, her blood boiled with excitement, but she also ended up feeling depressed. After all, she had never witnessed it, and she had never seen a real grown sheep. As for the many children born after her, they had never even heard of such things.

Yah’din had never dreamed that one day she would have a sheep. On that day, she held the sheep in her arms the whole night, not willing to let go even when it shit and pissed. People asked her what she would call it, and she said just Sheep; it’s the only one so there are no others to mix it up with. Fifteen years flew by, and Yah’din had grown up. Yet the sheep only grew a little, just reaching people’s knees. Things told in the legend—hooves the size of bowls and a body as tall as a person—were nowhere to be found.

It wasn’t like Yah’din didn’t worry about this. She asked around for tips on keeping sheep in a world that no longer had any sheep. The old sheep herders were all gone; the paintings in all the sandstone caves, big and small, were all eroded by the wind; the yarn paintings found in peoples’ homes were too dirty to tell what they depicted.

She recalled what the man had said when he gave her the sheep: feed it pure liquid water, bathe it in the sun, and walk it. Simple as that, nothing more. Nothing could go wrong. When she worried so much that she turned and tossed in her bed, the sheep’s almond-shaped black eyes saw through it all. When she lay on her back, the sheep, front legs leading the hind legs, jumped onto her, exhuming pride and energy. Its big eyes came close to her face and there was no trace of fear in them. What a beautiful sheep! Yah’din realized her sheep was just fine. After that, she never felt worried about the sheep again.

The alarm around her neck made a beeping sound. Time to fetch water. Yah’din hurried home to get the bucket from her yurt. Since spring, fetching water meant traveling several Long’rian miles. The old well had dried up completely.

She bumped into her Ma on her way out and instinctively, she turned her shoulders to shelter the sheep.

“Slow down!“ Ma shouted.

“I can’t. I have to be back in a bit to mend the yurt and plant the blue crystals.”

“There’s no hurry. I’ll wait for you.”

“I can’t. I have a schedule. If this is late, everything later will be all wrong.” She had already run so far that her Ma didn’t even hear the last sentence she said. Yah’din gasped for breath. She had said all this for her own benefit anyway. She was the one who wanted to learn from the outsiders, doing things in order and with plans. She bought a beeper and carefully set a schedule—starting such a task at such a time and finishing such a task at such a time.

But after a whole year, she was still all fingers and thumbs. From birth to death, people who grew up in a yurt never looked at a clock or used a beeper. Every day they just did whatever they were supposed to do. Their hands and feet just kept moving, and the things that needed to be done just happened like water that flowed naturally. One after another, they all got done. The Long’rians didn’t understand time, and they didn’t understand how something that had existed as long as the world could be cut into equal parts. Yah’din was different. She had resolved to learn to do things according to a schedule so that she could one day go outside and see the world. Yet making up her mind was easy; her body and brain still had catching up to do. Every day, she felt like she was being driven from task to task and got tired without knowing why.

She hadn’t considered the extra distance she had to cover to fetch water when she had made her schedule. Yah’din told herself that she needed to hurry up. She started to run, and the sheep began to bounce in her arms. Lucky that she had four arms, two for holding the bucket and two for holding the sheep; otherwise, she could never have managed it. Luckily the sheep was behaving now, just curling up and not moving. In the past, the sheep always poked its neck out and looked around, ready to snarl at whatever annoyed it. Now it knew more about the world so it became much quieter, and its body also got a lot heavier, as if the weight of silence was placed squarely on its back.

2

The water level had dropped again. They had to dig new wells. Yah’din straightened her back and carefully laid down the sheep. The sheep bent its hind legs, wobbled for a step or two, and plumped down. It leaned on the wall of the well to wait for her.

First, Yah’din dropped a bag of de-solidifier into the well and waited for the water inside to liquefy. She lowered the bucket into the water, filled it, and then pulled it back up. While she pulled the bucket up, the water inside it solidified again. Yah’din put the two buckets next to each other and climbed on top of the hill next to the well. She looked west and saw a block of green shrubs standing to attention on top of the red sand. So someone had been charitable again. The Public Welfare Forest had grown much bigger since she last saw it. The outsiders were keen on fixing Longgu’er’s sandland problem.

If someone donated the money for a shrub, the tree planter would plant one here. The shrubs sucked up water like crazy, and they were aggressive. Where they grew, no other grasses could; even the sandland animals avoided them. But the outsiders didn’t know. Yah’din scratched her head and looked around. Her lower set of hands went into her pocket and then slowly came back out. Some blue powder fell out of her pocket along the way. The Long’rians called it the blue crystal, a type of sand bacteria used for making de-solidifying and decomposing agents. Since time unknown, there had been a rumor among the children that blue crystals could stop the shrubs, and so there was always some child who spread blue crystals around the border of the shrubbery when the adults turned their backs.

“You are almost twenty. Why do you still fool around?” Yah’din’s Ma had spotted the blue powder around the edge of her pocket when she got home and given her a good talking-to.

“I checked and made sure there was no surveillance drone when I spread it,” Yah’din quibbled, knowing that if people really meant business, the surveillance satellite would have recorded her little trick.

“Reckless. It’s useless. Waste of blue crystal. As if you didn’t know there aren’t enough to go around at home.”

The beeper interrupted Ma. Time to mend the yurt. Yah’din took out the two buckets of solidified water and put them into the water storage, while her two other hands were weaving thread in preparation. Ma had already started mending the yurt. As she was berating Yah’din with verbal rapid-fire, her needles and thread followed the pace of her speech, so she had already mended the largest hole while speaking. The yurt was made from the skins of hundreds of sand lyre worms. It was light, thin, sturdy, transparent, and bug-repellant. Even so, it was no match for the gravel that flew around in a storm. Every now and then, they had to check the yurt. If they found any scratch marks, they immediately sewed it up. It would be too late if you waited until there was actually a hole in it. Yah’din had been doing this since she was a little girl, and her four hands were as nimble as Ma’s—as long as she did not distract herself by stroking the sheep nearby. Yah’din pushed her needle in against one scratch mark.

“I heard that houses outside do not need to be mended every day.”

“Me and your Pa won’t stop you. But don’t expect us to clean up after you.” Ma glimpsed at the sheep. The sheep laid its head on Yah’din’s legs, sleeping again.

“Sheep leaves with me.”

Ma’s four hands stopped. “You’re taking the sheep? You probably won’t be able to board the car to the liaison station, let alone a spaceship. You don’t even know what it’s like out there and you want to bring it with you?” Ma swallowed what she meant to say after that.

Yah’din broke Ma’s heart, so she dared not look at her and just stroked the sheep with her head lowered. The sheep raised its head and snuggled her hand with its wet nose. “You don’t know that, not without trying. Besides, no rule says you can’t bring a sheep,” Yah’din mumbled.

Ma’s hands moved again. “Two more months and you’ll be twenty, then you can do whatever you want.” The sheep moved into her arms, rubbed its face on her clothes, and licked her lazily. Yah’din held it and rubbed its back. If it had not been for Sheep, she probably wouldn’t want to go. Poor Sheep. All alone by itself. Yah’din wanted it to meet other sheep. She wanted to see a world with many sheep. But none of this could be said. A tree-planting drone flew past the yurt, leaving a lingering whooshing noise in its wake.

Ma stretched out a hand to beckon the sheep. The sheep didn’t budge. Yah’din put down the sheep and gently pushed it toward Ma. The sheep wobbled for a bit, steadied itself, and then stumbled on. Ma didn’t bother to wait. Instead, she held out her arms to lift the sheep onto her knees. She measured the sheep with colored thread. “I’ve got to make a rucksack for it, so you can travel with it on your back and don’t stand out too much. Next market day you should ask around to find out if they allow sheep on cars and spaceships.”

Yah’din found it even harder to look Ma in the eye. She picked up a ball to play with the sheep. The sheep waved its legs, moved close to the ball, and lay down at Yah’din’s feet. Sheep glanced at the ball, lowered its head, and stayed put. Yah’din frowned. “What’s the matter with it? It used to pester me all the time to play catch with it. Ma—is Sheep going to have little sheep?”

Ma pricked her finger with a needle and laughed.

3

They had dug out the yarn painting Granny left behind again. The last time was for figuring out why the sheep didn’t grow as big as it should have. This time, it was to prove that Ma was wrong.

The grownups weren’t shy about what went on between men and women. Even a toddler knew all about that. But it was different with the sheep. None of the grownups had ever seen one for real. How could they be sure what would happen? Even though Ma laughed at her, Yah’din still thought the sheep was pregnant. The way it looked tired was just like Ma when she was pregnant with Yah’din’s little sister. Ma didn’t say anything, just watched while Yah’din rummaged through things, and even gave her a hand digging out the loom.

Yah’din turned the yarn painting in her hands again and again, and looked at it from all angles. Like all yarn paintings on Longgu’er, it was an asymmetrical truncated cone. The yarns were woven together in a mysteriously complex way; the pattern was repeated regularly so that the warp and weft crisscrossed into vivid figures on all three sides. Even though time and sand had rubbed away much of the color, they could still make out the sheep, big and small. The sheep on each side were all different. But none of the pictures could tell Yah’din what was the matter with her sheep.

Yah’din didn’t know why she was panicking. The alarm beeped. Time to clean the blue house. Tomorrow the station chief would come to inspect it. Yah’din sulkily gathered the tools and headed out.

“Now don’t go messing around. Don’t go door to door asking to see people’s yarn paintings.” Ma guessed what was on her mind.

Without a sound, Yah’din went behind the yurt, squatted down, and dug open a section of sand. In the hole was a layer of blue crystals. She scooped up just enough, put them into a bag, and sprinkled some blue crystal spores. She covered the hole up and headed toward the blue house. The blue house was right behind the yurt. It didn’t look far away, but twenty minutes would go by before she got to it. Yah’din went ahead for a couple of steps and then doubled back to pick up the stumbling sheep that had followed her.

The first time she saw the sheep was by the blue house. It was there that the man who built the house gave the sheep to the five-year-old Yah’din. The man’s name was Li Shu, an outsider who came to Longgu’er to do maintenance and surveying jobs. Li Shu was handsome. Under his tight eyelids, his eyes were long and shiny like the edge of a knife. It was a pity that he was a cripple as he only had one pair of hands. He didn’t pity himself. Instead, he started building little blue houses. He said he would build one blue house for every family on Longgu’er. Yah’din told him that they had yurts and there was no need for these houses. He laughed, and his eyes became hook-shaped. The blue house was meant to be their outhouse, he explained to Yah’din.

It turned out that when he arrived in Longgu’er, he found no toilets anywhere. Whenever someone needed to take a dump or a leak, they just went somewhere empty and squatted down. He felt embarrassed. So he decided that he would make every Long’rian family enjoy the convenience of an outhouse. Yah’din only vaguely understood him. This outhouse was just a place for people to take a dump or take a leak. But why did you have to have a box to shut yourself in when you take a dump or a leak, and why was it embarrassing if you didn’t? The Long’rians never felt this embarrassment. It was such a huge place and as long as you didn’t splash some onto someone else, it was fine. It was only embarrassing when there was a pair of eyes on you. But who would be watching? Yah’din bit her lips. She knew she couldn’t explain this back then. Even now, she still couldn’t explain it.

Li Shu left fifteen years ago. But the outhouse he built still stood, and inside it was almost as new as it was fifteen years ago. The Long’rians didn’t make much use of it, dismissing it as a waste of water and blue crystal. Every time people up there sent someone to inspect, they grudgingly sacrificed a little bit of blue crystal and water to clean the blue house. Yah’din was quite good at cleaning it. She wiped the corners with a wet rag, sprinkled the least possible amount of blue crystals evenly, and finally sealed the door from the outside. Yah’din sat down with her back to the wall. The sheep was in her arms all this time, and now it raised its head to look at her. In the light, there was a white smudge in its eyes. On top of that smudge, there was a reflection of Yah’din. Yah’din laid her face close to the round forehead of the sheep. So warm.

Before meeting the sheep, Yah’din had barely hugged anyone or anything, and she had no idea what it was like to dive into warm breath and feel the weight of others. Ma had so much to do that she barely had time to stop for a moment, and Pa ran around following the irons in the sky, getting home perhaps only once a year. Besides, the Long’rians weren’t huggers. The sun was so hot that a body next to another only made one feel uncomfortable. Even the Long’rian animals weren’t huggers. Under the sands, millions of creatures had spikes or shells. They minded their own businesses and thrived.

“Did you hear that? What was that sound?”

“The crawlers and beasts are at it underground. Long’rian animals all live underground.” Except for the sheep, but they were all gone.

“So quiet.”

They sat shoulder to shoulder in the shadow of the blue house. Their eyes roamed and wandered over the vast and open land. There wasn’t a whiff of wind on that day either. Yah’din did not answer him. She thought she understood what Li Shu meant. Quiet meant they could hear all the soft and tiny sounds that were usually hard to capture.

“Just like the sound of blood coursing in you. When I was alone in space doing spacewalks, it was also quiet like this. So quiet that I could hear the sound of blood coursing inside my body.”

“Is it the same?”

“It’s the same.”

“Because you were alone?”

“Because the world you are facing is too big.”

***

A jet of hot air hit her face. It was the sheep breathing heavily onto her. Yah’din only opened her eyes halfway and held the sheep. “There is no hurry, we have to wait a little longer.” She was exhausted, and her eyelids felt heavy. She didn’t know whether she was dreaming or remembering, but she saw Li Shu again, sitting here with her five-year-old self. The house was only half built. In Yah’din’s memory, Li Shu was always talking. The blue house was always half-built. Yah’din fell asleep again.

She remembered Li Shu had told her water on Earth flowed around and its area was larger than land. The sky was blue, because of the refraction of atmospheric molecules. While he said all this, she tried very hard to imagine what that place was like, but she couldn’t help feeling sad for this man at the same time. He left Earth to survey “usable planets” in space all by himself, and he could not go back unless he had finished his mission or run out of fuel. What did it mean: “usable planet”? Yah’din didn’t understand that.

“You’re always alone when you are out there?” Yah’din asked him. Li Shu didn’t say anything. He just put his hand into a bulging pocket and took out a ball of curly red fur. The fur ball trembled a bit, and a pair of shiny eyes and a nose emerged. Yah’din couldn’t take her eyes off it.

“I’ve got him. This is a new species that can adapt to all kinds of gravitational conditions. It’s fine both in space and on the ground.”

“What is it?” The red fur ball suddenly stood up. Yah’din’s half-extended hand jerked back in fright. She stared at the fur ball, and the fur ball stared back at her, wagging its tail. “Is it a sheep?”

“It’s a dog. On Earth there is…”

“It’s really a sheep! It’s just like what I saw in the yarn paintings!“

“So it’s called sheep here? What are yarn paintings?”

Yah’din showed Li Shu the yarn paintings around the time he visited for the final time. She couldn’t remember how many times he came—their blue house took the longest time to build. She showed him the yarn paintings and a scale model of the loom. Ma had said that this model might be small, but it could be used to weave a yarn painting. Li Shu’s eyes lit up. He took the model in his hands and grabbed a card clasped in the model between his fingers. The card had lots of holes punctured through it, and he examined it carefully. Suddenly, he let out a cry, and his face became so bright that it was as if a spacecraft was taking off directly on it.

“The holes are so regular; they must have been created on purpose. This is a punch card! The loom controls the warp and weft as well as the movement of a third vertical thread according to the holes in the punch card. This card is where the machine stores its memory. The machine uses it to remember, to learn, to process abstract commands, and to complete complex tasks. Do you understand? This is programming. That is to say, you, the Long’rian civilization has already invented a computer.”

Li Shu’s words tore through her like a tornado. Yah’din didn’t understand, so she couldn’t remember the whole thing. Program, commands, computer, Long’rian civilization. Yah’din wanted to say that no one on Longgu’er knew what he was talking about, but she couldn’t open her mouth. She also couldn’t remember exactly what it was she had wanted to say back then. She only remembered Li Shu’s face and his eyes—even in her memory, in her dreams, she could not look directly into that blinding white light, that glare from the future.

Li Shu wanted the model. Yah’din gave it to him, and in exchange, her empty hands received a heavy, warm body. The sheep.

“For me?” Yah’din couldn’t believe it.

“Yep, you gave me your model.”

“What about you? You’re fine alone?”

“Doesn’t matter. I can re—” What did Li Shu say? Something like he would return. One day he would return. He said he would return.

Yah’din always woke up from her dreams at this precise moment.

She opened her eyes, waking up in the same patch of shadow that she shared with Li Shu in her dreams.

The blue crystal should have finished cleaning the house. One more wipe with a wet rag would be enough. Yah’din stood up and opened the door.

4

Yah’din should have known it would be like this.

On the morning that the chief of the liaison station showed up to inspect the blue house, Yah’din was busy planting blue crystals behind the yurt with the sheep. She was carefully scattering humus into the hole when she heard Ma complaining to the station chief that the blue house was a waste of water and quite a bother. No one ever used it, and it weighed people down. No one could migrate far because it needed to be maintained. Everyone was forced to pitch their yurt around it in a circle. Even if the groundwater was almost used up, you couldn’t move elsewhere. Why did we have to build this blue house? Why couldn’t this blue house be packed up and moved around like a yurt? The chief had heard these complaints a thousand times, so he just mumbled something in response while carefully inspecting the blue house. The chief was responsible for all external affairs. If something went wrong with the blue house, it was his job that was on the line. He found no problems during the routine inspection, so he said his goodbyes and got ready to leave.

The sheep, who had curled up under Yah’din’s feet, wanted to see him off. Its four legs struggled to support its body and then they failed. It came crashing down, making quite a noise. In Yah’din’s mind, it was like a dune had just collapsed.

Yah’din scooped up the sheep and stopped the chief in his tracks. “Give me a ride.”

“To where?”

“Your place.”

“Where?”

“The liaison station. I want to send a message.”

“Knock it off. What message? To whom? That liaison station of mine stopped working a long time ago.” The chief looked at Ma with a diffident smile on his face. Ma said nothing. “Didn’t I help you send messages before? To the guy named Li Shu, right? No answer at all. It’s not just your message; we have so many serious things that we need to discuss with them, but none of the messages we sent them got a reply. To think, they built this liaison station for us and asked us to keep the communication open. The outsiders are like that. All they know is planting trees here for fun. They build this and build that, but they never really use them.”

“Don’t you message them every time you finish inspecting the blue houses?”

The chief didn’t answer. Yah’din turned around and climbed into the chief’s sheet-iron car. She held the sheep in two hands and her other two hands grasped the seat tightly. Ma walked up to the car and looked at her through the railings. Yah’din opened her mouth, but only whimpers came out; she couldn’t say anything. Ma stroked the sheep in her arms, again and again. The sheep didn’t respond. Its body heaved. All of its strength went into breathing.

“If…Come right back,” Ma stammered.

***

It was dark when the chief drove Yah’din back home.

This time, Yah’din had watched the chief send out her message. She waited a whole day. No reply. Ever since the sheep’s eyesight became weak, she had been asking the chief to help her send messages. She asked Li Shu what was wrong with the sheep, and what she should do. She said she couldn’t live without the sheep. No reply. Yah’din thought maybe it was because the lazy chief didn’t bother to send the messages—until today when she stood there and watched him send it right in front of her. On her way back, she held the sheep tightly with all four hands. Between going to the station and coming back, the sheep seemed to have suddenly lost quite some weight.

The middle of the road was bumpy, and the car’s caterpillar shock absorber didn’t work. She talked to the sheep gently, as if she was afraid that her voice would hurt it. The sheep raised its eyelids and searched for Yah’din with its nose. When it had found her, it gave Yah’din a long look, and then its eyelids crashed shut as if it was separating itself from the world from now on. Yah’din felt like she had fallen into emptiness. She felt nothing but discomfort. She wanted to curl into a ball, to hold the sheep tight, and to contract her skin, her blood vessels, and her muscles.

Ma asked Yah’din to lie down and go to sleep. That was when she came to. She was already home. She looked down at the sheep and the sheep was as oblivious as she had been, just lying there limply.

“Want something to eat?”

Yah’din saw that the sheep was not about to wake up, so she shook her head.

“Don’t get too obsessed with it. It’s just a matter of time. The sheep gets old too, just like people.” Ma tucked her in.

But what did Ma know? She had never raised a sheep before. How could a sheep of fifteen be old? Yah’din turned her back to Ma. The sheep was still asleep in her arms. Just like before, the two of them slept face-to-face under the same quilt. The tip of the sheep’s nose was such a curious thing, wet and black, and covered with fine patterns like someone’s fingerprint. Sometimes Yah’din thought that even if the Long’rian deserts were covered with sheep in the future, she could still find her sheep by the patterns on its nose. She didn’t sleep well, dozing in and out of consciousness. In the middle of the night, she heard winds shrieking outside the yurt and its tarp flapping loudly. When she listened again, she heard the shrill wail of the wilderness. The tarp was torn open somewhere, and sand poured inside. Yah’din covered her mouth and nose. Suddenly, the sheep jerked a few times and white foam started to come out of its mouth. Yah’din hurried to get it on its legs, patted its back, and cleaned its mouth and nose. When the sheep stopped jerking, she leaped to her feet.

“Where are you going?” Ma shouted after her.

“I’m going to Pa. Maybe he knows what to do.” Yah’din lifted the yurt’s curtain and rushed into the darkness, carrying the sheep in her arms. She only managed a few steps before she stumbled and almost fell. The wind forced her back. Yah’din wrapped the sheep with her cape and walked with her head down. Sand and gravel buffeted her. She was in too much pain to tell exactly where her body hurt. It was too dark. She only had the small flashlight installed in the cape to illuminate her way, and the tiny beam of light reeled with her in the storm. She didn’t notice a rock under her feet and fell. The wind pinned her to the ground. Suddenly, she became aware of an emptiness in her arms. Where was the sheep? Yah’din panicked. She crawled around, felt around in the dark, and shouted “Sheep! Sheep!“ Her mind kept thinking of the sheep lying on the ground motionless. She felt desperate and scared. Something black and sticky started to burn inside of her, fanned by the wind outside. Her desperation flapped in the wind like a flaming flag. Where was her sheep?

Something covered her. Like someone would put a blanket over the flames when fighting a fire. Yah’din became more aware of her surroundings. She realized Ma was holding her. Where was the sheep? She asked Ma.

Something soft and warm fell into her arms. Her palm felt wet. The sheep was licking her hands. “Been following you all this time. It fell a few times but it kept following you. If I hadn’t come out, you would have lost it,” Ma said.

Yah’din couldn’t open her mouth, so Ma spoke first: “Let’s go. Let’s go find your Pa.”

5

They got out of the car and Ma pushed her into Pa’s tent. All three of them couldn’t stand up straight inside, so they just sat down, facing each other, staring at each other.

Ma told Pa what had happened in a few words, and asked whether he knew any way to save the sheep.

“What would I know?”

Yah’din avoided Pa’s eyes. The man in front of her was almost a stranger. Pa spent his time picking up irons in the wasteland, and she had only seen him a few times her whole life.

“Talk.” Ma poked her in the arms.

“It’s not like we need you to know how to save the sheep. Can you make contact with the outsiders?” Yah’din choked up. “Hasn’t Pa been picking up the irons that fall from the sky? Aren’t these irons sent up there by the outsiders? They use them to survey Longgu’er and they have to upload their numbers somewhere, right? Can we send them a message together with the numbers?”

“The numbers are sent to the liaison station. They compile the numbers there and then send them on,” Pa corrected her.

“I’ve been to the liaison station. They haven’t heard back from them for years.”

“I’ve heard there are important irons. The numbers there are uploaded directly,” Ma said.

“Those are long gone. They came down a long time ago and we picked them clean and sold them for scraps.” Pa scratched his head. “It’s been years. Since you’ve been at home, you wouldn’t know about this. These irons have not been attended to for so long. Nobody is sent out to maintain them anymore, and certainly, no one is doing field calibration. Only the tree planters work now. The reason we can make a living out of picking up the irons is that these irons are scrap, they’ve fallen out of the sky after all. Many people are now saying that the outsiders have left us alone.”

“Left us alone?”

“In the past people said Longgu’er might be put to some big use. Later it seemed the outsiders changed their mind. They just left us alone, which is good. People say that if Longgu’er is put to use, all of us will have to move.” Pa and Ma droned on about some unrelated things, moving the topic further and further away from Yah’din. She felt as if she was out there in the dark all by herself again, with her back bent up against the slashing wind. But this time, the sheep was here. Her sheep was fine right here in her arms and close to her chest. She could feel its heart, beating at the same pace as her own.

“He...They won’t come back,” Pa said gingerly.

“In the past, many people on Longgu’er only met them once or twice in their lifetime, and they just gave each other something to remember them by. That man who built the blue house accepted our model loom. In the future when he sees…”

“It has nothing to do with him. I just want to know how to save my sheep,” Yah’din interrupted Ma.

“Don’t.” Pa clumsily patted her on her back. But Pa didn’t say that a sheep was nothing to be sad about.

Yah’din rubbed her nose and moved sideways to allow Pa’s big hand to come through and land on the sheep. “Ah, still this small. Just the same as when it first got here.”

The sheep shivered, but it was not a convulsive movement. Heaven knew where it found the strength to stand up and turn its face aside to rub against Pa’s hand.

Once. Twice. Thrice.

That took all its strength. The sheep slid down Yah’din’s arms limply.

6

By the time they got back to the yurt, the wind had stopped.

Nothing moved between heaven and earth. So quiet.

Ma stood aside, watching Yah’din take out the loom and the yarn painting without saying a word. She searched for more but turned up nothing. Yah’din began to unravel the yarn painting. This was the only yarn painting left by the elders. Yah’din found a loose end and, without hesitation, started pulling. Ma said nothing. She just squatted down to hold the yarn painting for her.

Yah’din wound the yarn into a ball as she unraveled the painting. In her other pair of hands, the sheep didn’t stir at all.

She should have thought about this, that one day her sheep would die all alone. Its tiny body joined the past and the future together, the outside and Longgu’er, Yah’din and Li Shu, as well as her and the sheep’s fifteen years of life.

This was life, but it was also so much more than life. Everything was tangled into such a mess. Even if you had four hands, you still couldn’t sort it out. Every pull hurt.

In the past, she tried everything but failed to find a single person who knew how to raise sheep on Longgu’er. Now, she tried everything but failed to make Li Shu and the outsiders tell her how to save the sheep.

On her way home, she asked Ma whether she knew how to use the loom. Ma said she would try to remember. Yah’din asked Ma to teach her. “I want to weave a yarn painting, to weave my sheep into it. An exact likeness. So I’ll never forget it.”

“You can try. But there are probably no extra yarns. You’d have to unravel the ones we have. Yarns are all passed down by the elders on Longgu’er. The younger generation unravels the paintings of the older ones to make their own. Your granny said the skills to make yarn disappeared a long time ago. Even her granny didn’t know how…”

Yah’din didn’t care as long as there were yarns. She wound the yarn into balls and erected the loom, following Ma’s instructions step by step. It wasn’t hard, she just had to use both her hands and feet. And she had two pairs of hands. She put the sheep on her legs. Its head drooped off her lap. She held up the tiny head and placed it securely on her legs. It was the last sheep on Longgu’er and Yah’din’s first sheep. They had been together since they were both little. It connected her with the world, trusted her, and relied on her.

“Understood?” Ma asked.

Yah’din nodded. She learned how to weave. One move of the needle made a loop; the warp, the weft, and the vertical yarn all interwove into place. It was still too early to tell. But soon. Soon. Almost there. Her sheep was about to appear in the yarn painting. That was her sheep, the last sheep on Longgu’er, but also the best sheep in the universe. It never caused any trouble. After fifteen years, it was still warm and soft and wonderful.

Ma stepped aside. She knew there was nothing to worry about now. Yah’din had learned it. Some lessons had to be learned sooner or later. Ma watched as tears streamed down Yah’din’s face, and felt heartbroken. She thought: this is water, water flowing from her eyes.

Epilogue

Like dandelion seeds scattered by the wind, one hundred and twenty people were ordered to head into space, combing the immense universe for planets fit to become deep space quantum communication relay stations. They piloted their spaceships alone and faced unknown challenges. Li Shu was one of them. This was a mission to find a needle in a cosmic haystack. Apart from searching for a quantum communication relay planet, the surveyors were also to gather field data and maintain equipment on all allied planets along their route, assessing the possibility of also transforming these worlds into relay stations. If no naturally suitable relay planet—with the right environment and the absence of intelligent life—were found, one of the planets in the United Alliance would have to be transformed.

On one gamma-class planet called Longgu’er, Li Shu traded his canine companion for a model of a punch-card loom from the local people there. Aside from the more traditional weaving functions, the machine also seemed to possess primitive memory storage and automation functions. Li Shu speculated that it was not just a weaver, but also a computer. If this was true, it would mean that the indigenous civilization had developed to a rather advanced stage. Earth must pay more attention to them. To prove his hypothesis, he tried to figure out how to use the loom but failed.

There was another failure. After all the data from Longgu’er had been compiled, the final calculation indicated that this planet was not suitable to be transformed into a relay station. Li Shu gave up. He soon forgot about his two failures and forgot Longgu’er. He continued traveling among billions of stars and their solar systems, searching for one suitable to become a human deep space quantum communication relay station.

Just two days ago, he finally got the news that one of the surveyors had found an appropriate relay station planet. Li Shu ruminated on the news in silence. He eventually felt a huge sense of euphoria. Inside his white zero-gravity space cabin, he imagined how his comrades would be celebrating in space and on Earth. Finally, he could go home.

If he had not been traveling back to Earth, he probably wouldn’t have noticed the message from Longgu’er. He was sorting through the artifacts he had collected on his travels—reducing his ship’s load to make sure he had enough fuel for the return journey. The model loom suddenly started moving. The colored yarns, arranged horizontally and vertically on the machine, suddenly wove themselves into an asymmetrically truncated yarn cone. Li Shu couldn’t discern a pattern. The wild and disjointed patches of color could hardly be called patterns. Li Shu was creeped out. The loom kept producing wild colors, the likes of which only a brain on the brink of madness could imagine. Had he been alone for too long, or too excited about being able to go home…?

Suddenly, the loom stopped. The axle of the punch card turned, and the position and number of holes changed. Li Shu picked up the card and looked at the yarn painting through one of the holes. He recognized the pattern—Yah’din’s sheep.

Li Shu suddenly realized that the Long’rian loom, which he thought was a computer, was a communication device beyond human understanding. An ancient technology that used to be widely used on Longgu’er—but had been forgotten by the people there as their way of life changed and certain species went extinct. The humans who discovered Longgu’er couldn’t understand this technology either. They would never have believed that this uncivilized land had once owned the long-distance communication technology they dreamed of possessing.

Particles that vibrated inside the microtubules of the yarn could entangle with particles half a universe away, and change their status. Because of the three-dimensional nature of the yarn painting, the vectors describing the status of the particles could exist in a space with limitless dimensions. This meant that this communication technology had limitless potential.

Humanity almost missed this technology that had come so close to them. While they were busy constructing pathways for quantum communication across the universe, they overlooked the equipment and technologies already in their hands. This was not Li Shu’s problem. Humankind could only accept things that they were willing to accept, and facts that didn’t fit within their existing strains of knowledge were imperceivable to them. Luckily, the sheep had extended Li Shu’s own strain of knowledge.

Now that he had received the message, Li Shu adjusted his flight coordinates for Longgu’er.

“You know that in quantum physics, measurement is not just a simple process of display, but participation in the evolution of a system. In this sense, Yah’din’s love for a ‘sheep’ is a measurement that participates in the evolution of two civilizations. It has changed deep space communication, changed the future of humanity and the destiny of the entire universe,” Li Shu said to the cloned dog sitting behind him.

Author’s Note:

When asked about my creative process, I always feel anxious because my life is quite dull or, you could say, tranquil. Really, nothing much dramatic happens, especially compared to my journalist friends. On the other hand, I’m lucky to be able to live safely and be in good health. Considering the tragedies afflicting this planet right now, I wish more people could choose a calm life and focus on creating beauty. I write about alien worlds and beings, their loss and pain, but fundamentally I write about trying to find a path to live and love.

Threads in the Cosmos | Short Story is a story from our issue, “Online Odyssey.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.