Chinese films that impressed at the International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam this November

Chinese films lit up the screens at the 2023 International Documentary Festival Amsterdam (IDFA) this November, and the entrants took an introspective turn with stories focused on individuals and families.

Along with the handful of new Chinese films entering the festival, “Guest of Honor” director Wang Bing also selected a host of older Chinese documentaries to play. Wang is famed for Tie Xi Qu: West of the Tracks (2002), a 9-hour saga that documents industrial decay in northeastern China, and told an audience at the festival: “It’s our own emotions, our own fates, our own fortunes and misfortunes that I would like to focus on in my movies.”

Apart from Wang’s selection of his favorite independent documentaries (and another selection of his own films), several new movies demonstrated his sentiments on screen by lending an intimate lens to people’s lives in China. A mockumentary on an ordinary woman’s “rebellion,” an observation of party-goers in Chengdu, a day-in-the-life portrayal of workers planting trees in the desert, a pitch for a film about casting strangers as the director’s mother… Among the Chinese voices selected at the IDFA this year, many were young, and the majority were women.

Here are three spoiler-filled reviews of the best feature-length Chinese documentaries shown at the festival this year:

The Last Year of Darkness

Funky Town is the size of a streetside noodle shop, sandwiched between a pizza joint and a construction site in Chengdu, Sichuan province. But it is also one of the most important sites for the city’s underground nightlife scene, and the central stage of The Last Year of Darkness, a film that follows the lives of some young regulars.

Though the profuse B-roll shots of construction sites, fanatic crowds, and old people exercising in parks are tired tropes, the story makes bearing them worthwhile. The way American director Benjamin Mullinkosson visualizes the story’s social backdrop might not be free of the typical expat gaze, but the raw emotions in his portrayal of each protagonist show his deep connection and respect for them.

A drag performer, a delivery driver who parties at night, an emotionally volatile guzheng player… As Mullinkosson peels away the dazzling packaging of the night lights, he knits together a group portrait of these young people whose life choices often don’t comply with society’s expectations.

The story flirts with heavy topics like mental health, feeling lost in life, and dealing with family as a queer person. But when Yihao, the drag performer, talks about childhood trauma with a chuckle and moves on in a few seconds, Mullinkosson doesn’t push for more. Dark humor often intervenes in the images of “hard-knock life,” inviting the audience to laugh along with the protagonists.

Unlike in Queendom, a Russian film about a vocal non-binary drag artist that made the top three of IDFA’s Audience Awards, queerness in Last is not interpreted as a fight for justice or identity. Rather, the protagonists are allowed to be ordinary people, each facing unique struggles but also embodying relatability.

In one powerful scene, Yihao turns to the camera and tells Mullinkosson, “I don’t think you can really document my life.” The reality, Yihao says, doesn’t come through careful editing but is something that one needs to experience to understand. The moment gives Yihao the space to take the initiative to defy the confines of the film.

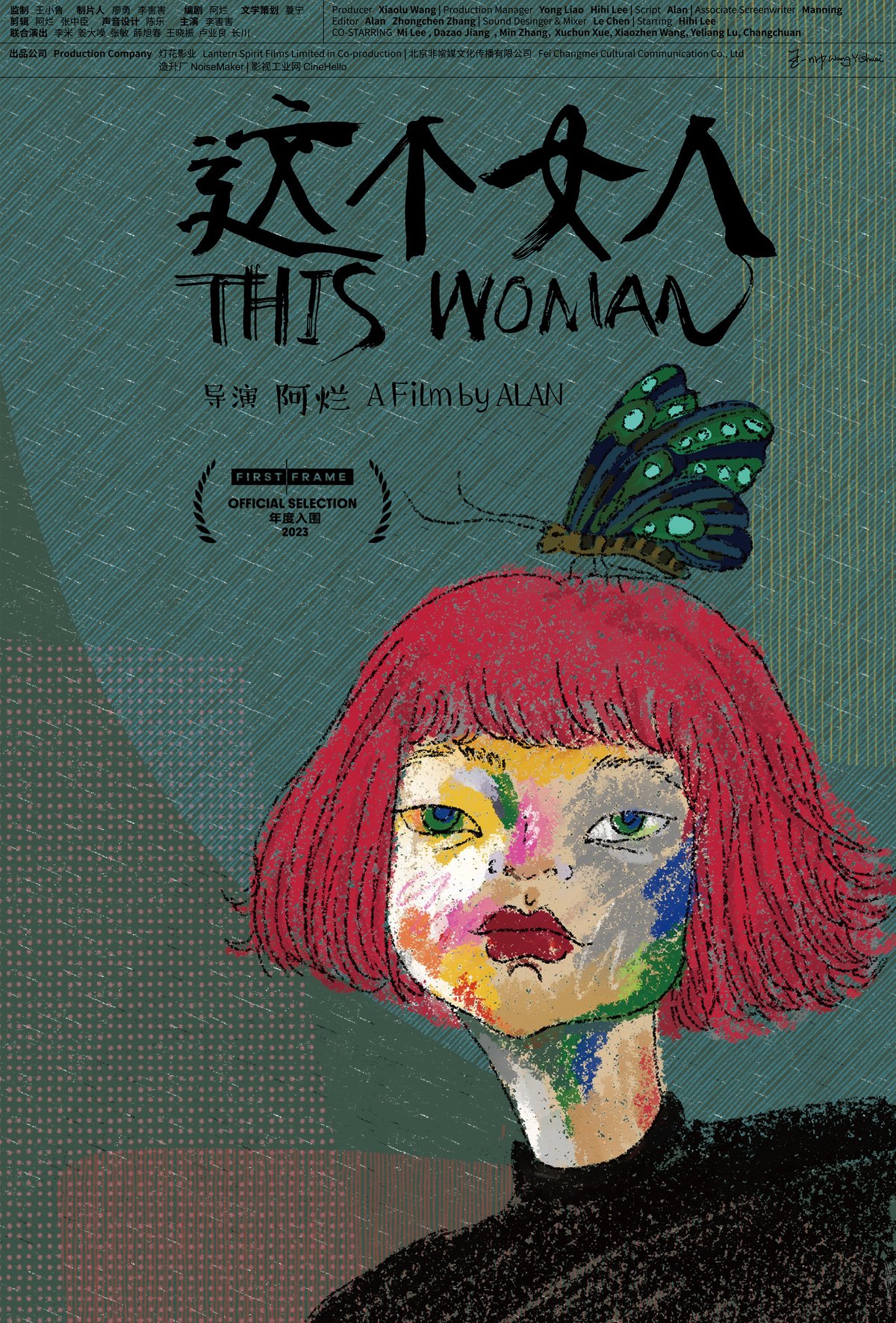

This Woman

This Woman opens with the main character Beibei talking straight to the camera: “I think I’m a pretty standard wife.” Next, we see her sharing hotel beds with a man while video calling her young daughter who is left with dad while mommy is away.

Some audience might have already met Beibei, a 30-something office worker ordinary on paper, through other international film festivals this year including FIRST in Xining, Qinghai province, and Visions du Réel in Nyon, Switzerland. Beibei got married and had kids “on time.” She saved up to buy small properties; she dressed generically. But her contradictions slowly mount as we see her leaving a stable job in Beijing to move back to her hometown in Fujian province, or going from lover to lover without tearing through the facade of her marriage.

Debut director Alan, also a new mother in her 30s, writes in the synopsis that This Woman “immerses us in the life of a woman who refuses to let her identity be defined by others, who demands the right to find out for herself who she is and what she wants.”

That makes the movie seem cliche, but Beibei’s life is more nuanced than Alan lets on. In Amsterdam’s Pathé Tuschinski theatre, the audience laughs when Beibei plants 10 burning cigarettes in front of her father’s grave, sniffles when her ill grandma tells her “You look a lot like Beibei,” and falls quiet when she debates with her mother the boundary between freedom, responsibility, and motherhood.

Beibei never cites grand feminist discourse to make sense of her decisions and experiences. Nor is this a story of trauma or oppression like many films centering on Chinese women. Rather, it shows how one individual navigates her place within the constraints of her society without defying its complexity.

The film leaves its most powerful punch for the final scene, however. Beibei reveals that the whole film is not a “real documentary.” Beibei’s story is partly scripted based on the life of a woman named Li Haihai and played out by herself. The revelation leaves the audience wondering where fabrication broke from facts (and where truth hangs in between) and in shock by the power Li Haihai asserts by using the medium to interpret her own identity.

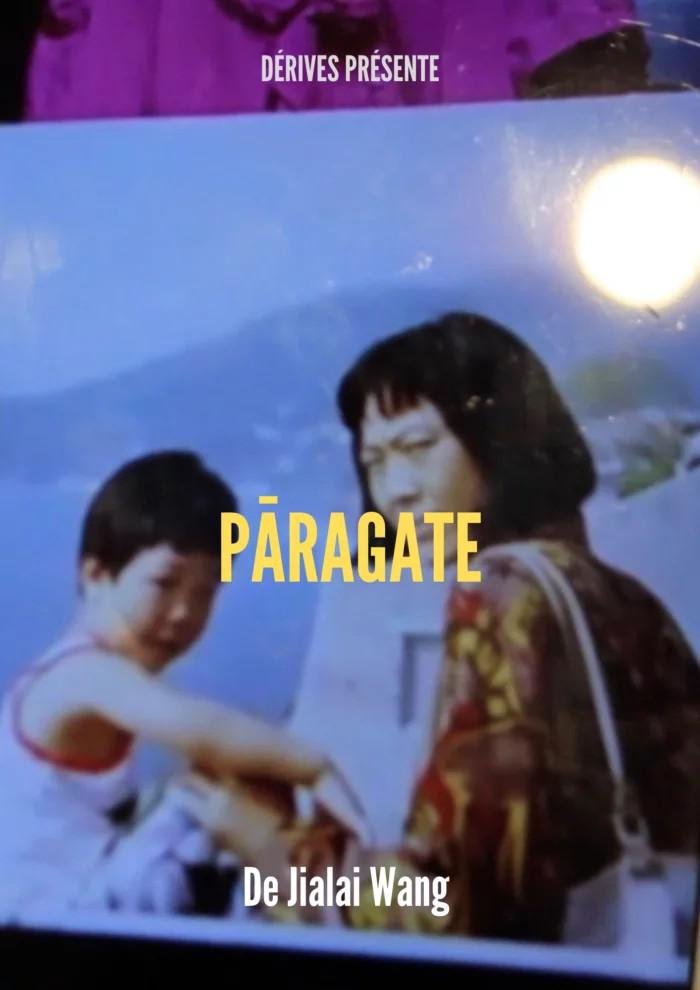

Paragate

Paragate begins in an almost hypnotic fashion. Jialai Wang, a Brussels-based director, diligently films her video calls with her mother in Shanghai during the Covid-19 pandemic. The audience hears about her mother’s growing dedication to Buddhism, and her grandmother’s deteriorating health.

It’s a story of Wang navigating difficult intergenerational relationships with her family against the backdrop of the new virus. After months of video calls, her camera moves away from the phone screen and to real life as she visits her family in China.

Emotions in the film are complicated by the different mediums Wang’s relationships are filtered through. Just as the audience starts to feel uneasy at how often Wang checks her camera during her calls, as if filming is more important than the conversation, she confronts her mother about a childhood incident where her mom had threatened to kill her. And just as we question the ethics of her seemingly intruding into an older couple’s Shanghai home with a camera, the conversation reveals that these individuals are new tenants in her grandmother’s home. It also becomes apparent that her grandmother was also abusive to Wang’s mother.

In these scenes filled with a delicate tension between offense and vulnerability, Wang almost seems to use the camera as a shield to navigate excruciating topics in her life.

Unfortunately, the second half of the film loses focus as Wang wanders the streets of Shanghai. Here, her lens lingers on half-finished construction sites, elderly people dancing, customers scanning a QR code to pay for products, and her mother watching a military parade—it’s like a check box exercise in capturing “China spectacles.”

The film becomes more awkward when Wang approaches a street cleaner, who appears to have no interest in being interviewed and pesters him with relentless questions about why he is unhappy.

Perhaps all this could be justified as emphasizing the feeling of an estranged emigrant looking back at a former home. But Wang turns herself into a caricature-like outsider character, and it’s unclear if she does that with awareness or purely through internalized exoticism.

Luckily the emotion flows again in the finale. Mother and daughter’s troubled relationship returns to the fore until Wang’s mom recounts how a Buddhist teacher taught her a scripture with the meaning “Save me, mother.” With this short scene, Wang’s mother, equal parts cruel and vulnerable, becomes human again.