Bar-based lecture series are becoming increasingly popular in the capital, attracting students and workers looking to learn and find community outside of traditional educational spaces

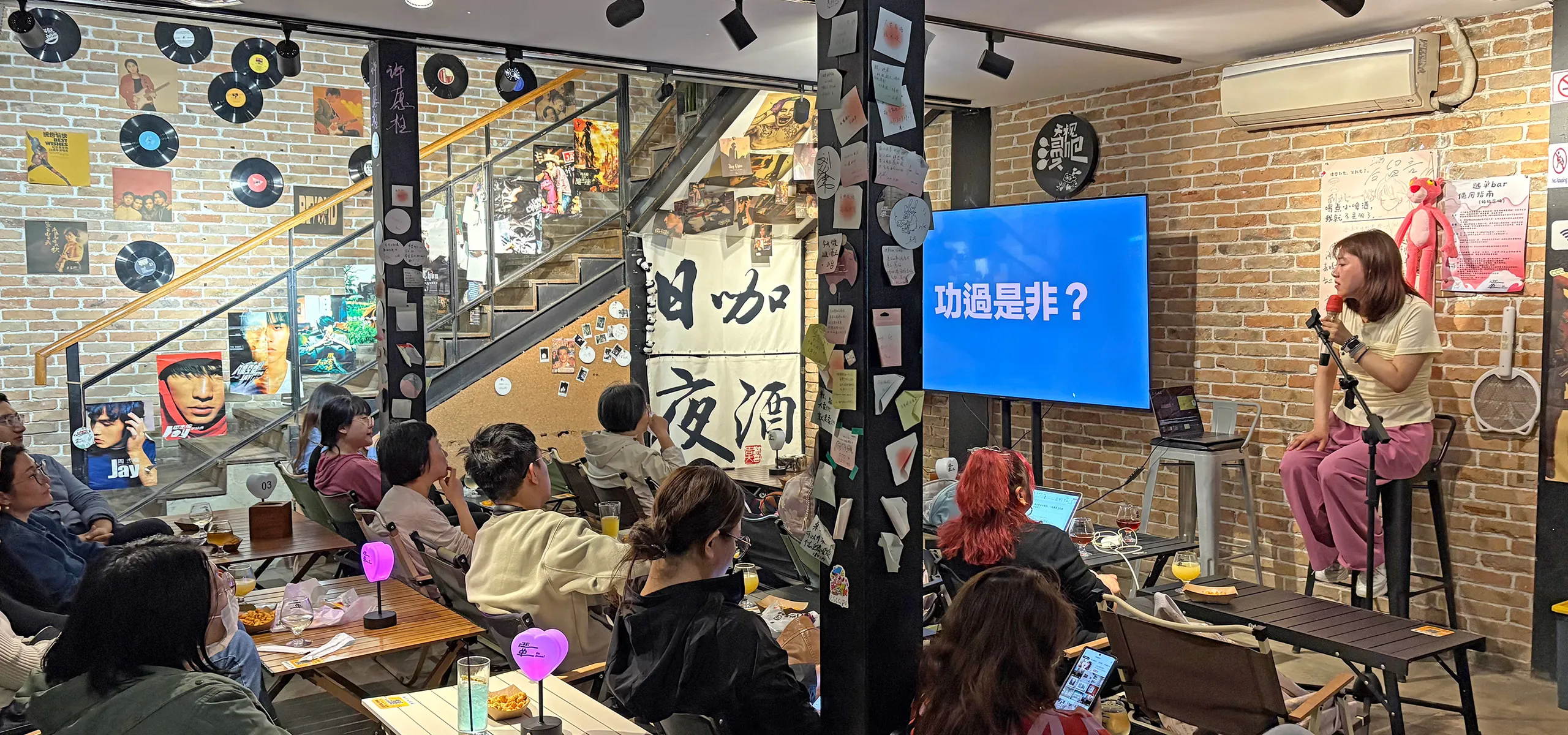

On a Sunday night in Beijing, doctoral candidate Ding Jiayi stands before an audience of 40 people—all nursing cocktails—and walks them through the particulars of traditional Chinese medicine. Though her slides are dense with historical texts and scientific findings, many of them drawn from her own research, she quips throughout her talk, often pausing to poke fun at the mystique surrounding TCM.

“Oh,” she laughs, stopping abruptly halfway through her lecture. “I’m actually pretty hungry. Let me eat a snack, OK?” She opens a pack of crackers, and her audience breaks into applause.

This is the first of 14 April lectures hosted by Universe Salon (宇宙客厅), a program that invites academics and industry experts to discuss topics of their choosing at bars across Beijing. The particular venue—E Cubed, where Universe Salon began—especially suits the program’s name. Sixteen stories above the Haidian district, its golden stage lights twinkle like stars. Ding’s enthusiasm for TCM is infectious, and her audience clings to her every word with rapt wonder.

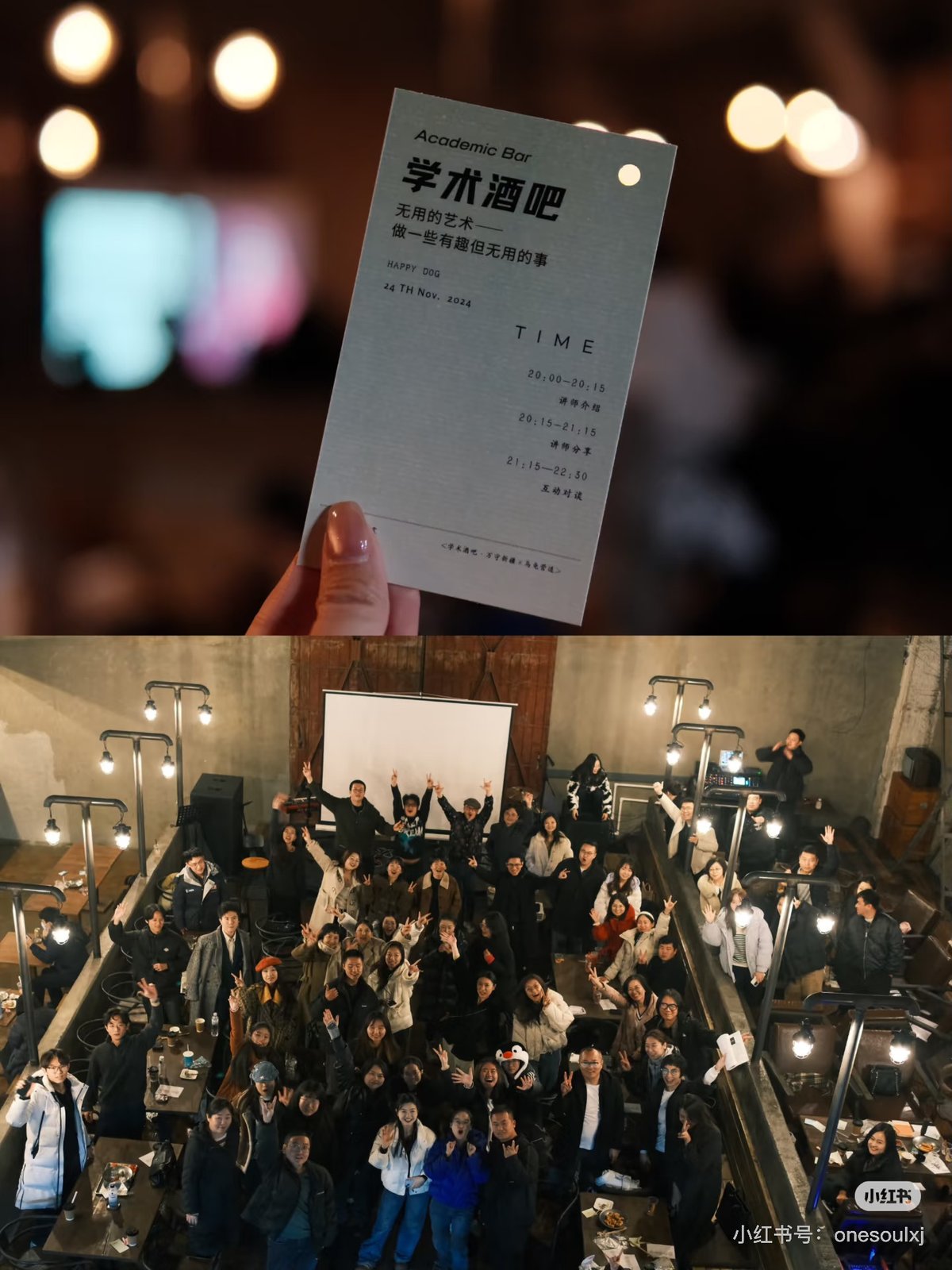

Over the last year, academic bars have exploded in popularity across Beijing and other major Chinese cities. For many students, recent graduates, and workers, these events promise specialized knowledge and community outside the classroom. For lecturers, they provide access to eager and diverse audiences who bring surprising new insights to their disciplines. However, the cost of entry—usually the price of a cocktail—can still be a barrier for many urban residents.

Read more about China’s night scene:

- Why China’s Young Urbanites Seek Refuge in Night School

- Where Red Pepper Meets Rosé: Yunnan and Guizhou Flavors Fuel China’s Bistro Craze

- Mixing Equality: Why is it So Hard for Women to be Bartenders in China?

Zhang Jianchen, the founder of both Universe Salon and E Cubed, had always wanted to create a space for informal academic discussion. After four years of working as a bartender, the 20-year-old opened the bar in 2023. His first lecture was a collaborative effort between a group of Beijing-based undergraduate students and professors, who had proposed hosting their own event at E Cubed. Inspired by the camaraderie between students and professors, Zhang launched Universe Salon in the summer of 2024.

Since then, Universe Salon’s team has welcomed dozens of professors, students, industry professionals, and even members of government to talk at bars across the city, resulting in a vast repertoire of lectures across numerous fields. His requirements for lecturers are looser than those of other academic bars across China, which may only consider lecturers holding PhDs or tenured positions at prestigious universities. “We look for teachers who have specialized knowledge and who know how to teach an engaging class to a diverse student body,” Zhang tells TWOC. “Other qualifications don’t matter as much.”

His vision of a fun and accessible academic space has paid off, earning features in numerous publications on Beijing’s nightlife and weekend scene, along with a strong following across social media platforms. “We’ve struggled with audience overflow on several occasions,” Zhang tells TWOC. “It’s hard to predict which subjects will draw in bigger audiences, since they’re all popular.” Though he asks interested attendees to confirm participation on Xiaohongshu, or RedNote, audience members may show up without warning, standing when there is no room to sit.

Now, Universe Salon offers multiple lectures simultaneously, hosted at E Cubed’s many partner bars across the city’s central districts: on a single night, followers can choose between a talk on artificial intelligence in Xicheng, a class on Han dynasty music in Dongcheng, or a lecture on traditional Chinese medicine in Wudaokou.

“Who can tell me what qi really is?” Ding asks, promising an E Cubed coupon to whoever answers correctly. But there is no need for such an incentive: half a dozen audience members leap to respond. Ding engages with each answer earnestly, before joking that all of the respondents—a physics student, a computer scientist, and a doctoral candidate in philosophy—should join her team of TCM researchers. “Traditional Chinese medicine isn’t always considered a credible field,” she tells TWOC afterward. “It’s too abstract for many people.” In exchange for explaining TCM in a simplified and accessible manner, she receives a slew of new insights from her audience members, most of whom work in different disciplines. “Academic discussions usually happen behind closed doors, resulting in echo chambers,” she says. “If I don’t put in the effort to attend events like this, it’s quite hard to hear from people outside my field.”

Zhang first asked Ding to speak after seeing one of her posts on Xiaohongshu, offering her a share of the profits from the event. As someone who had already attended several Universe Salon events, she eagerly accepted and is just as excited to return in the future. When not conducting research, she teaches classes to an online audience. But she much prefers the energy of an academic bar, where people usually approach her lectures with curiosity rather than criticism. “It’s easy to be attacked online,” she says. “Some netizens doubt the efficacy of TCM, and others disagree with my specific findings. It can get pretty brutal.” While it is common for her in-person lectures to instigate discussions and debates, Ding says the audience tends to be much more respectful toward her and each other.

Wang Sixuan, who has patroned Universe Salon’s lectures for months, believes that the audience’s diverse perspectives and disciplines, which draw from shared curiosity towards the world, are precisely what makes academic bars so appealing. “Interdisciplinary discussion is often the launching point for new scientific frontiers and policies,” he tells TWOC. Wang, who is currently visiting Beijing on an extended business trip, spends most of his time working in anti-smuggling policymaking in Guangdong province, where he and many of his colleagues are usually focused on their immediate work. “If I discuss social issues, history, or literature, I tend to be considered an outsider,” he continues. He was electrified by the atmosphere in E Cubed, where audience members engaged in discussions on everything from philosophy to “dreams about changing the world.”

Bar owners and researchers aren’t the only ones tapping into the potential of academic bars. Zhou Yuan, the founder of Bowen Travel and Tourism (博文行旅), a Beijing-based travel company, recently decided to organize similar events to raise awareness and foster enthusiasm toward aspects of China’s traditional culture. Her company currently offers several travel itineraries, such as city walks in the capital, ancient mural tours in Shanxi, and trips to Japan’s cultural heritage sites, but she sought to add a relatively accessible and low-commitment option to her roster. This March, she reached out to various bars, looking for venues willing to host academic lectures, and put out a call for lecturers on Xiaohongshu.

Fang Yuan, a doctoral candidate at the China Academy of Arts, responded to Zhou’s call. Within a month, the two organized their first event at Taodan Bar. The bar, located just outside Beijing’s Yonghe Temple, is a fitting venue for the topic at hand—Emperor Qianlong’s 18th-century rule—given that he was born there. “Can you think of a contemporary country that doesn’t tax its citizens?” she asks her audience of 30, who sit before her on foldout chairs. “For many years, the Qianlong Emperor didn’t tax his subjects.” Her audience murmurs in appreciation as she walks them through the emperor’s love for calligraphy and his system for appraising artworks.

“There aren’t that many opportunities for the average person to learn about ancient history,” Fang tells TWOC. Many of the educational events hosted by museums and libraries fall during working hours, conflicting with students’ and workers’ busy schedules. Fang had not expected her audience to be so enthusiastic about her subject, nor to have so much fun lecturing. After her talk, she engages her audience members in discussions, recommending books and documentaries to more avid attendees. While neither Fang nor Zhou earns any profits from hosting academic bars, since all drink revenue goes to the bar, Zhou does get an opportunity to promote the cultural trips offered by her company to the targeted audience that Fang draws in. Zhou aims to continue hosting academic bars about China’s traditional culture every month, hopefully at a variety of bars across Beijing.

Ming Yilan, who requested to be interviewed under a pseudonym, was one of the guests at Fang’s first lecture. A graduate of Peking University who now works in education, he has spent almost a decade in the city, where he gained a deep appreciation for its culture. He tells TWOC that Beijing’s long history and density of universities mean that it is uniquely positioned as a beacon for more inquisitive individuals, who are likelier to spend their free time attending such lectures. Like Wang, the regular at Universe Salon, Ming believes that it is the company of these individuals, and the conversations that ensue after the lectures, that are the main draw of academic bars. “People loosen up over alcohol and tend to offer more sincere insights,” he says. “We might be learning about a serious subject, but there’s none of the pretense that you’d find in a classroom.”

While people of all backgrounds are welcome to attend academic bars, almost all of the audience are white-collar professionals or students. Universe Salon’s venue—a 10-minute walk from the nearest metro station and situated squarely between Tsinghua University’s south gate and Peking University’s campus—makes it a convenient location for students looking for an evening activity. Meanwhile, Taodan’s location in central Beijing is typically frequented by middle-class patrons. At both bars, attendees must purchase at least one drink—ranging anywhere from 60 to 90 yuan—to sit, a barrier for entry that puts such events out of reach for many Beijing residents.

“For 60 to 90 yuan a lecture, I wouldn’t go very often,” says Di Di (pseudonym), a recent college graduate in social work. “I might attend a lecture once every month or two, depending on how interesting it looks.” After graduating, Di Di turned to books, discussions with friends, and free online content as her primary means of gaining new knowledge.

Wang Junying, who completed her master’s degree at Tsinghua University before beginning work in outdoor education, agrees that attending academic bars may be a costly pursuit for recent graduates. “So much of the access to urban communities and knowledge these days requires money,” Wang tells TWOC. “Sometimes, it feels like I’m trading one hour of work [income] for one hour of fun.” According to the higher-education consultancy MyCOS, the average income for China’s graduating class of 2023 is 6,050 yuan per month. Meanwhile, the Beijing government reports that the city’s average consumer spending per month stands at around 4,000 yuan. Though Wang understands the value of academic bars, she says that she would only attend them sparingly, depending on whether the subject piqued her interest.

Still, academic bars are one significant step toward democratizing education in an increasingly specialized world. Zhang, founder of Universe Salon, believes that they will only become more popular as people seek out the communities and access to knowledge that they lost after graduating from college. ”We hope people can form friendships with each other and the lecturers through these events,” he tells TWOC. “At the end of the day, everyone needs an outlet for their curiosity.”

How Beijing’s “Academic Bars” Are Helping to Democratize Knowledge is a story from our issue, “Smart Nation.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.