Qin Tian’s award-winning film exposes the growing pains of Chinese urbanization through the lens of gender

A woman dreams of leaping from a rooftop. The scene then cuts to her clutching her luggage on a shaky bus, her small figure reflected in the window as she travels from the countryside to the city in search of work. As director Qin Tian tells TWOC, “I aimed to document ordinary souls battling the tumultuous tides of our era.”

Qin’s film Fate of the Moonlight, also known as Moonlight Sisters, draws inspiration for its Chinese title from the renowned ci poem by the 11th-century poet Su Shi (苏轼), particularly the well-known lines, “May we all be blessed with longevity/ Though miles apart, we’ll share the beauty of the moon together (但愿人长久,千里共婵娟).” While the film initially appears to focus on the individual fates of three generations of women, a deeper, more universal theme emerges as the story unfolds: The vast chasm between city and countryside that persists in China’s ongoing urbanization, which, perhaps even more than their gender, becomes the core force driving the fluctuations in these women’s destinies and shaping their hardships.

Find more female-centered films:

- Like a Rolling Stone: A Stirring Meditation on Womanhood and Defiance

- The Female-Perspective Films Enriching Chinese Cinema

- The Rise of Female Perspectives in China’s Movie Industry

Winner of Best Narrative Feature at the FIRST International Film Festival in 2023, the film earned just 480,000 yuan at the box office after its mainstream release this June. But the 172-minute film still received strong critical acclaim and currently holds an impressive 7.5 out of 10 rating on the review platform Douban.

The film is set in Chengdu, where the towering skyscrapers not only underscore the historical reality of rural-to-urban migration but also subtly hint at the psychology of the characters. Protagonist Xia Chan (played by Xu Haipeng) is a microcosm of her generation, as a rural-born woman plunged determinedly into the whirlpool of urban desires like countless other youths at the turn of the millennium. She quickly discovers that, without the “passport” of an urban household registration (hukou), it is immensely difficult to secure stable work and a sense of belonging in the city. The dense, towering urban skyline visually manifests the sense of oppression that urban spaces give to outsiders like Xia Chan.

As China’s demographics and urban landscape undergo transformation, the social spaces and status of women are also changing. Qin tells TWOC that he saw the explosive growth of Chengdu’s population by millions within a short period after 2010, and some of the pivotal plot points in the film were directly inspired by those growing pains.

In the film, Xia Chan’s departure from her hometown strikingly echoes that of Nora, the protagonist of Henrik Ibsen’s play A Doll’s House. Yet unlike Nora’s iconic act of liberation, marked by “the slam of a door” as she exits her husband’s home forever, Moonlight follows its three female protagonists of three generations as they move between rural and urban spaces: leaving, staying, and returning. As the identity of each character changes alongside the trajectories of her migration, the story reconsiders the definition of womanhood.

For Xia Chan, leaving the village was a rebellious act, an attempt to carve out a new identity for herself amid the changing times. Yet, trapped within the liminal space between city and countryside, her rebellion remained perpetually suspended, unable to take root. Denied a hukou, Xia Chan is forced to try to please powerful people, attending endless dinners, and offering bribes in a desperate attempt to secure a place in a school for her daughter, only to lose all her money in the end. Even seeking justice is futile: When the man who took the bribe refuses to give a refund, and finally admits he is actually powerless to help, Xia Chan does not use the knife she had hidden in her pocket, but becomes resigned to this reality and looks doggedly for other ways forward.

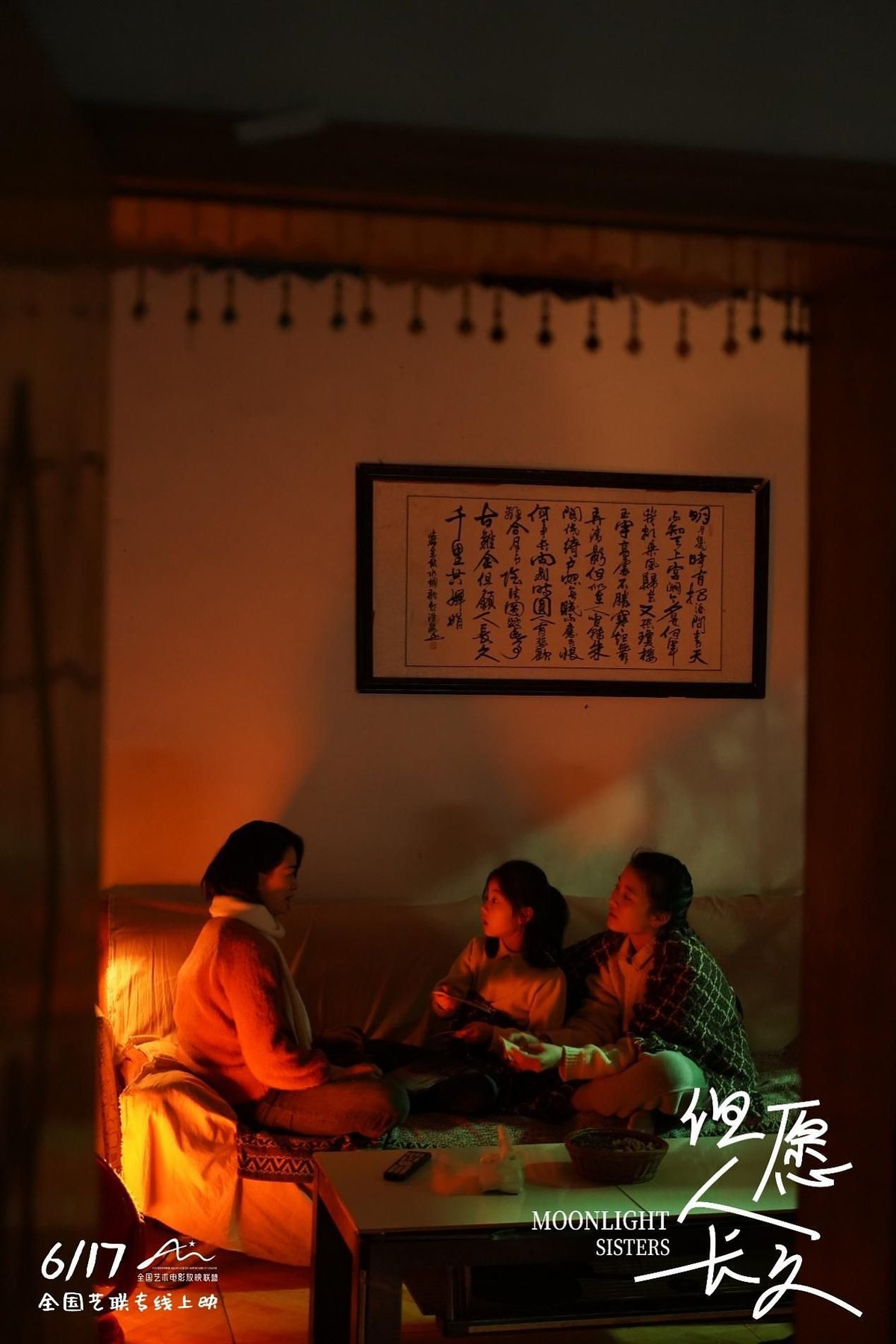

The second part of Su Shi’s poem that inspired the film’s title, “Though miles apart, we’ll share the beauty of the moon together,” mirrors the bond between Xia Chan, who left their small village, and her twin sister Xia Juan, who stayed behind. When Xia Juan’s daughter, Xia Xiaomang, comes to the city and seeks shelter under Xia Chan’s roof after her mother’s passing, Xia Chan is initially cold. She allows her own daughter to bully Xiaomang (Lian Yajia), repaying moments from her own childhood when she had to make sacrifices for her younger sister. In the moment when she finally embraces Xiaomang into their fold, pledging “we’ll live together forever,” the poem crystallizes into reality on the screen: Three women squeezed onto a crumbling balcony, their laughter rising as they hang laundry under the moonlight in a reunion steeped in the tang of everyday life.

Another character, Xia Chan’s mother, represents a generation of rural women who remain behind in the village. She eventually comes to Chengdu to try to reconcile with her daughter, only to become lost within the towering cityscape, swindled by a fake monk into spending 35 yuan on a worthless talisman. The film presents a visually arresting image: the elderly woman’s stooped and disoriented figure, swallowed by the cold, vertical forest of skyscrapers. Alienated from the rural “acquaintance society,” where finding a person was as simple as asking extended family members or neighbors, her search for her daughter became an arduous, nearly impossible task.

At the film’s conclusion, Xia Chan, weathered by city life, returns to her snow-covered hometown. In a scene that is visually expansive yet desolate. The profundity of Moonlight lies in its piercing revelation that this homecoming is fundamentally futile: Xia Chan can neither truly integrate into the city, nor can she seamlessly reintegrate into rural life, having become a guest in her former classmates’ lives and even more of a stranger to their values.

The closing aerial shot plunges vertically downward, casting a god’s-eye view over mortal existence. Xia Chan walks the highway with her daughter and niece, their boots crunching over half-frozen earth where stubborn patches of snow linger. They move forward, without looking back, toward the waiting bus, toward Chengdu beyond it, and unnamed tomorrows after that. No declarations, no tears: Only three parallel trails of footprints stretch ahead like a wound torn open and stitched shut, again and again.

Fate of the Moonlight: Three Generations of Women in the Crack Between City and Countryside is a story from our issue, “Urban Renewal.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.