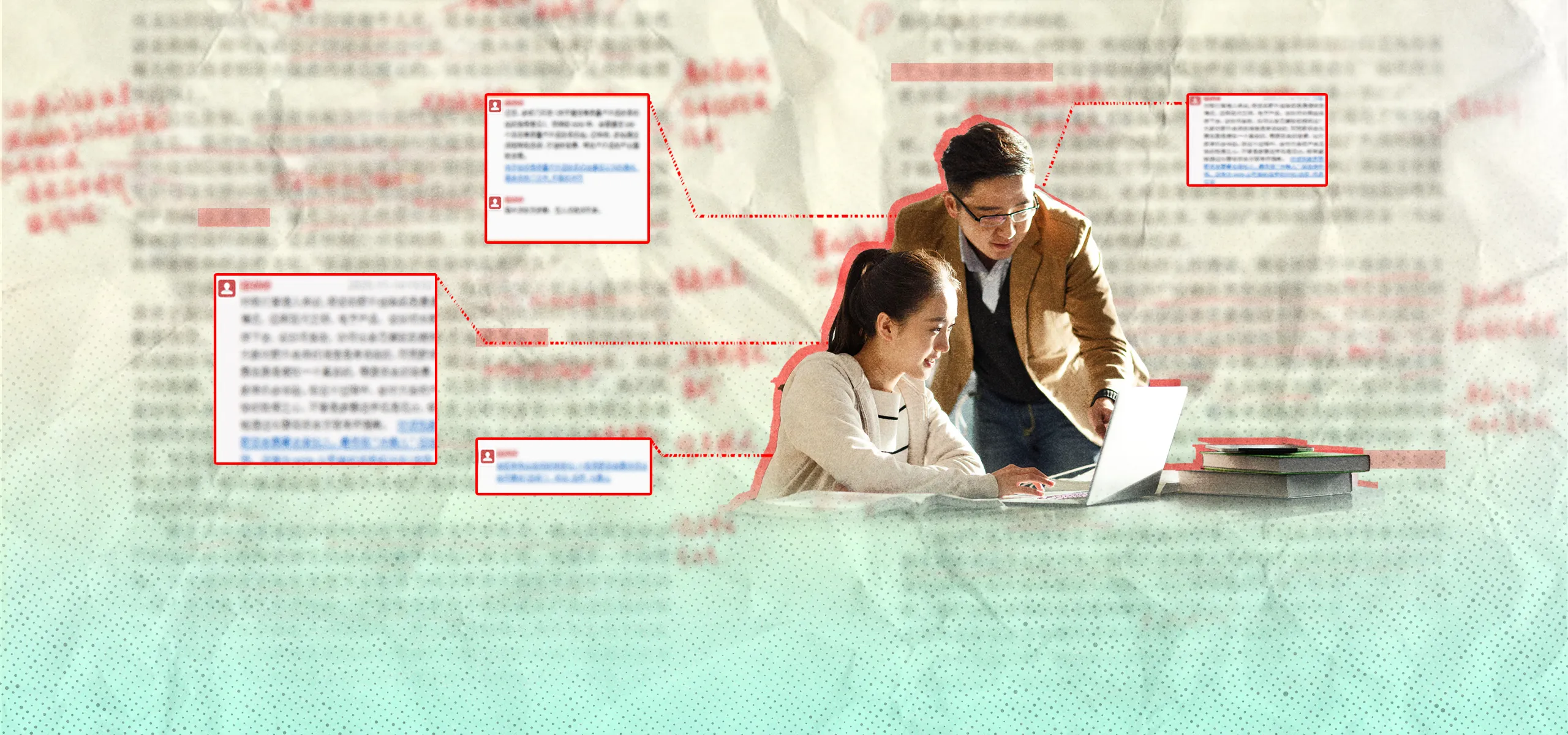

Under the looming pressure of graduation and thesis defense, students and their mentors have resorted to academic sarcasm to cope with stress

If you’re a Chinese student aged about 21, December is anything but a season for joy: When their Western counterparts start preparing for Christmas, Chinese 应届生 (yīngjièshēng, final-year college students) are typically scrambling to pick a research topic for their graduation thesis (论文 lùnwén), which needs to be proposed (开题 kāití) and approved by their academic supervisor (导师 dǎoshī) before the end of the year.

On university campuses, the atmosphere grows noticeably tense, since “thesis-writing doesn’t just wear out the student—it also wears out the supervisor (写论文这件事,有时候不光废学生,它还废导师 xiě lùnwén zhè jiàn shì, yǒu shíhou bù guāng fèi xuéshēng, tā hái fèi dǎoshī).” By graduation season, “either supervisor or student will surely go crazy (导师和学生总得‘疯’一个 dǎoshī hé xuéshēng zǒng děi ‘fēng’ yí gè).” Before they reach the 答辩 (dábiàn, thesis defense) stage, most students will submit multiple rough drafts for their supervisors’ eagle-eyed corrections.

Red pen of death

For students who are not confident about their topic, any comment from the supervisor can feel like a death sentence.

The style may vary, but the essence never changes: relentless questioning, exhausted condemnation, and a magical ability to make your last drop of confidence evaporate. Question-style rebuttals (反问型批注 fǎnwènxíng pīzhù) are common:

Evidence? Is it just because you say so?

依据呢?你说是就是啊?

How can you still get it wrong when you’ve copied it?

怎么抄都抄不明白?

Sometimes they even sow seeds of doubt about your entire academic career so far:

What exactly is your research target?

你研究的到底是什么?

Exclamatory marks may increase further down in the draft, revealing the supervisor’s full descent into emotional meltdown:

Typo!!

错别字!!

Delete this all!!

全部删掉!!

Some supervisors prefer a softer approach—but intentionally or not, this can turn into sarcasm (阴阳怪气 yīnyáng guàiqì) that leaves even more emotional damage:

This part is well written, but it needs to be deleted entirely.

这段写得很好,但需要全部删掉。

Even encouragement can sound strangely backhanded:

Hurry and finish up the next few sections, then you can rewrite them.

下面这几节快点写,写完就能重写了。

And sometimes, they’re just throwing shade—with the panache of an academic:

Your data-processing method reminds me of modern art: it looks deep, but I can’t understand a single part of it.

处理数据的手法让我想起了现代艺术,看起来很深奥,但我完全看不懂。

Students can only cry:

Even the way educated people scold others feels different.

文化人骂人就是不一样。

Plagiarism pains

Behind the professors’ pickiness is a genuine epidemic of plagiarism and academic dishonesty on Chinese campuses. In 2019—famously known online as “Year One of Tianlin (天临元年)”—actor Zhai Tianlin let slip on a livestream that he had never heard of CNKI (China National Knowledge Infrastructure), China’s largest academic database. Since Zhai’s PhD from the Beijing Film Academy was a big part of his brand, his admission prompted an outcry and a nationwide investigation into academic fraud.

Zhai has since had his PhD revoked and can no longer supervise students. All other students now must submit their work for rigorous checks by anti-plagiarism software. Depending on the major and the university, a master’s thesis with more than 15 percent similarity to existing sources is often flagged for further review. Thus, students pulling all-nighters in the library cry in despair:

Tianlin…can you sleep? I can’t.

天临你睡了吗?我睡不着。

Generative AI has introduced new challenges. Over the past year, many universities have belatedly issued guidelines for AI use in academic work, but many students have already become reliant on it. AI plagiarism-detection software is also causing anxiety, even for students who haven’t fully relied on AI, as they may still be flagged by the system. Many find this use of AI on modern campuses deeply ironic:

Students write papers with AI, schools check papers with AI—a full-on AI showdown. It’s truly surreal.

学生用AI写论文,学校用AI查论文,主打一个AI对冲,太魔幻了。

Teachers’ pain

But it’s not only students who are suffering—thesis revision can truly push both sides over the edge. With university enrollment numbers continuing to rise, and faculty jobs getting more precarious and demanding, it’s no wonder some supervisors dread opening their inboxes to tens, if not hundreds, of half-baked ideas, plagiarized paragraphs, and AI-generated word salad. They complain:

The comment boxes are so long, it’s like I wrote a second thesis.

批注框比正文长,像是自己写了个论文。

Sometimes the quality of a thesis is so low that professors don’t even want to be credited in their students’ acknowledgements page. One student shared online that their mentor simply said:

Don’t thank me for being rigorous—if I were truly rigorous, your thesis wouldn’t have passed.

不要夸我严谨。我真认真起来,你们的论文根本过不了。

But of course, behind all the sarcasm and self-deprecation, most supervisors do want to push their students to do their best and help them graduate (毕业 bìyè). Eventually, they hope, students may start to learn from the comments and spot errors on their own. As some students say:

I often delete my own writing without the slightest regret, as if taming my narcissism.

我经常毫无留恋地删掉自己写下的文字,仿佛也是在驯服我的自恋。

In recent years, the necessity of graduation theses has been debated by experts in China. Critics see them as an outdated formality for skill-based degrees. Students who have done little previous writing in their courses are suddenly asked to conjure a 15,000-character paper before they can graduate. The immense pressure is a recipe for academic fraud, while marking and anti-plagiarism duties also leave professors with little time to do their own research. Other experts, however, argue that writing, research, and critical thinking are the essence of any university education.

In any case, both faculty and students can let out a sigh of relief when spring comes and the final marks are out. As many students have reflected on this time period:

I bounce back and forth endlessly between giving up and polishing until the moment of submission lets me return to normal life.

在摆烂和精修之间反复横跳,直到交稿才过上正常生活。