Since their conception, the micro-drama format has been in constant flux, but does a new injection of capital—boosting production values and drawing big names—as well as interest by the state and companies abroad, really spell a more refined future for the genre?

After quitting micro-dramas for good, Liang You, a 28-year-old short video editor from Hubei province, thought she was done with them—until one pulled her back in.

Back in late 2022, when China’s micro-drama boom began, Liang was among the format’s earliest fans. She had binged countless one-minute love stories filled with billionaires, betrayals, and instant revenge before growing tired of their absurd plots. “Those old-school romance clichés—it was crazy but satisfying,” Liang tells TWOC. “But after a short while, it all felt the same, so I just stopped watching.”

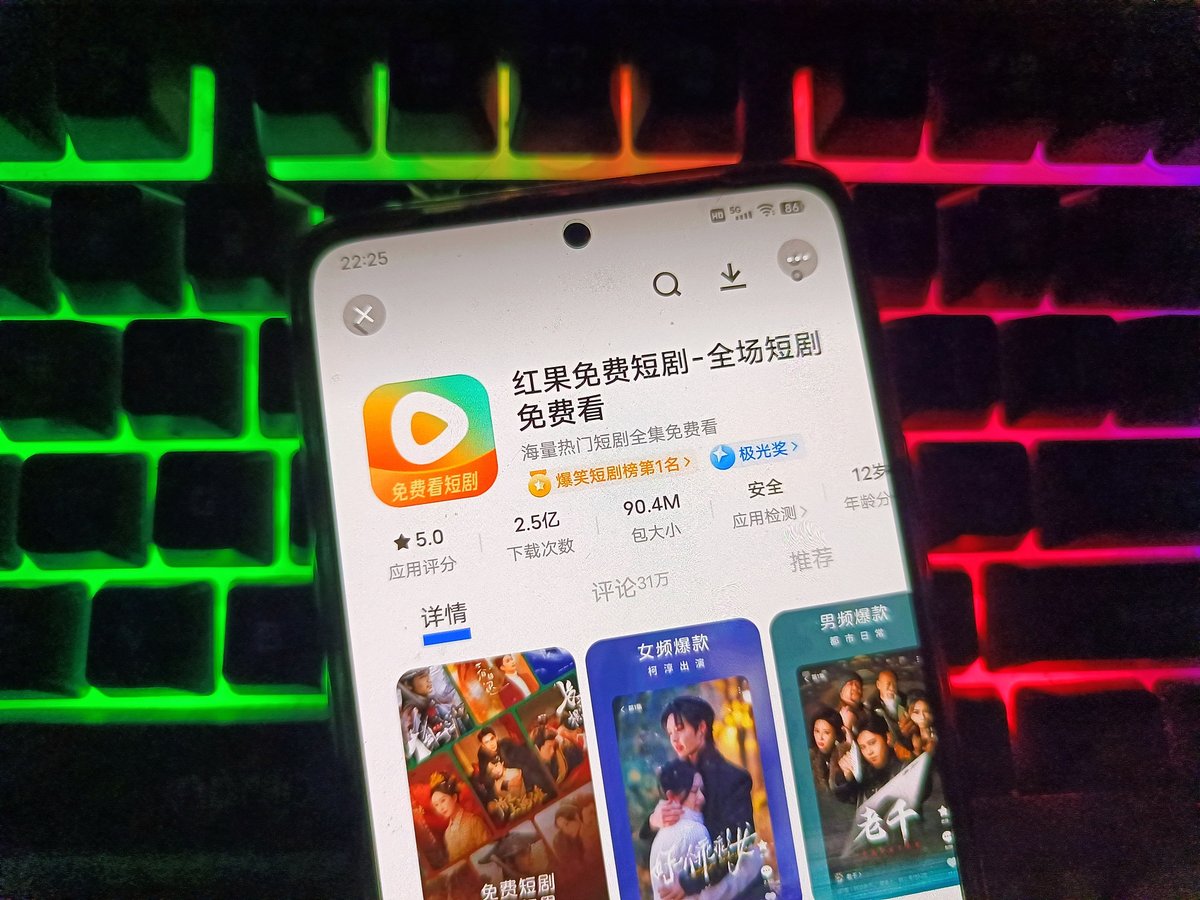

Now, more than two years later, she’s returned to her old routine, this time on Hongguo, a leading Chinese app for micro-dramas. What drew her back was Summer Rose, a deftly told romance with grounded characters and high production values.

“In the past, micro-dramas would pack a twist every 15 seconds, a plot push every 30, and a cliffhanger in the final 10—and I’d still watch them at triple speed,” Liang tells TWOC. “But this one feels completely different. It unfolds slowly, without all that flashy, over-the-top melodrama.”

Explore China’s latest micro-drama trend:

- High Stakes in Short Takes: China’s Booming Micro-Drama Business

- Short, Absurd, and Addictive: Welcome to the Micro-Drama Nation

- Podcast | How China’s Micro-Dramas Spread At Home and Abroad

Since premiering on September 20, Summer Rose has taken the platform by storm—amassing over 1 billion views in just four days, doubling that within a week, and soaring past 3 billion by October 7, setting the record for Hongguo’s fastest-growing micro-drama. Viewers have since hailed it as “the finer fare of China’s micro-drama kingdom.”

Beyond Summer Rose, micro-dramas in China are looking increasingly less like disposable entertainment and more like a legitimate storytelling form. The genre, once dismissed for its cheap production and cookie-cutter plots, is now attracting star-studded casts, bigger budgets, and growing critical acclaim. But as the term “premium micro-dramas” becomes a Chinese media buzzword, the question remains: has the industry truly leveled up, or is it simply repackaging old formulas with glossier production?

“The age of slapdash, low-budget micro-dramas in China is over,” Han Wenwen, CEO and founder of the Short Drama Alliance, tells TWOC. That’s because, she explains, “Production costs have risen significantly.”

Han notes that the average modern micro-drama with 65 episodes today costs around 500,000 to 600,000 yuan to produce, while costume or period pieces often run between 800,000 and 1.2 million yuan per series—and that’s without any top-tier actors. Just two years ago, TWOC reported that many micro-dramas were shot for less than 100,000 yuan—often filmed on a single smartphone, balanced on a cheap tripod, with no professional lighting, and wrapped within three days. According to Han, the leap in cost and craftsmanship reflects how the once rough-and-ready format is maturing into a legitimate industry.

According to TWOC’s review of publicly available data, production budgets for China’s most-watched micro-dramas this year have risen sharply. My Sweet Home, a breakout hit that captured audiences with its use of Sichuan-Chongqing dialect and a heartfelt story of a blended family surviving the region’s great 1980s floods, reportedly cost over 3 million yuan and took 17 days to film. Every detail—from costumes and props to set design and character styling—was steeped in nostalgia for the era, while local culinary inclusions like guokui (crispy flatbread) and danhonggao (egg pancakes) stirred something deep in viewers’ collective appetite.

Summer Rose, meanwhile, was produced on an even grander scale. With a reported budget of 8 million yuan spent across 11 days of shooting and nearly three months of post-production, the series achieved what many described as a “cinematic texture.” Through its canny cinematography and carefully composed shots, such as framing through latticed windows—leading some to call its director, Zhang Dama, “the Wong Kar-wai of micro-dramas”—the show highlights what East Asian romance storytelling does best: restraint, tension, and lingering emotion that stays with the viewer long after the screen fades to black

Despite improvements in costuming, production quality, and character arcs, critics argue that micro-dramas remain constrained by a deeper structural flaw: the stories still run on the same old circuitry. Much of the genre leans on predictable tropes—rebirth revenge, status-flip romance, emotional payback delivered precisely on cue. These formulas offer quick jolts of satisfaction, but they flatten lived complexity into a set of repeatable emotional shortcuts.

To many observers, the so-called “premiumization” of China’s micro-dramas is still very much a work in progress—uneven, imperfect, and only recently nudging from its chaotic trial-and-error roots toward hints of maturity. It passes as entertainment, technically—but hardly with finesse.

Nevertheless, that hasn’t stopped the form from accelerating, with another major shift becoming impossible to ignore: mainstream stars are now stepping into the micro-drama world. Former household names in China, such as Wallace Huo, Liu Xiaoqing, Huang Xiaoming, and Pan Changjiang, have all recently appeared in micro-dramas. Their motivations vary. Some see the format as a space to experiment or reinvent themselves; others enter with a mix of curiosity and unease. Pan, a 68-year-old veteran comedian often described as a “master of the old school,” admits he agonized over the decision, worried that the genre’s reputation for crude production might undermine his long-earned credibility. Sitcom actress Lou Yixiao, meanwhile, has taken a more active role—serving both as producer and actor in hopes of raising the bar from within.

“The micro-drama market is an undeniable windfall. It’s simply too big for anyone—celebrities included—to ignore,” says producer Huang, who requested to be identified only by their surname. The numbers bear that out. According to the China Internet Development Report 2025, released this November at the World Internet Conference in Wuzhen, Zhejiang province, China now counts 662 million micro-drama viewers, and the industry generated more than 50 billion yuan—surpassing the national box office for the first time. Just two years earlier, the entire sector was valued at 37.39 billion yuan. The leap is striking: what was seen as little more than disposable mobile content has become one of China’s fastest-rising storytelling economies.

“Whether a micro-drama features a big movie star doesn’t matter much to me,” Liang tells TWOC. “What’s more interesting is how many previously unknown actors have been discovered because their shows went viral. In the end, it’s the content that draws me in.”

Indeed, star power doesn’t always translate in the micro-drama universe. When the 75-year-old veteran actress Liu Xiaoqing released her second micro-drama Fortune from Above this July, her name alone seemed enough to guarantee attention. Yet two days after its debut, the series remained quietly afloat, drawing just over 3 million views on Hongguo.

“Micro-dramas aren’t becoming ‘premium’ because of long-form drama star power,” Han tells TWOC. “A celebrity cameo might help with visibility, but it’s little more than marketing decoration. What feels like ‘premiumization’ now is really the industry adjusting to new commercial pressures—and to an audience whose expectations have grown.”

According to Han, the reason micro-dramas changed wasn’t creative ambition but simple economics: the old “hook-click-pay” model still exists, but it has become increasingly difficult to convert paying users and stay profitable. Platforms poured huge sums into Douyin traffic, but as the number of dramas exploded, audiences became less willing to pay—an inevitable pattern in any maturing market. With 80 to 90 percent of budgets consumed by promotion, writers leaned into ever more outrageous hooks—violence, moral provocation, or even sheer absurdity, such as a woman giving birth to 99 babies—to rile emotions and drive impulsive clicks. “Anger is easy to trigger,” Han notes. “When people are angry, they often act without thinking—and sometimes even pay out of impulse.”

By 2024, even those shocks had started to lose their edge. Audiences had grown largely desensitized and increasingly tired of formulaic reversals, and the old tricks could no longer guarantee attention, let alone payment. At the same time, platforms were steering studios toward an advertising model—free content with embedded ads—which already accounted for about 46 percent of micro-drama revenue in 2024.

“Because ad revenue and profit shares are tied to watch time, the incentives didn’t disappear overnight—they simply shifted,” producer Huang tells TWOC. “Shocks still exist, but they matter less now; what counts more is retention, emotional continuity, and a more polished, brand-safe tone.”

Policy has played its part too. What began as one of the internet’s loosest, wildest spaces for creativity has been reined in step by step—first under the broad short-video rules of 2021, then the 2023 “clean-up” campaigns, and finally in 2025, when platforms quietly pulled hundreds of micro-dramas in a single month due to everything from sexual innuendo and copyright breaches to hyper-violent plots and warped moral messaging.

Any lingering ambiguity vanished last summer, when regulators made it official: every micro-drama must now be registered before it can go live. The message to studios was unmistakable: the era of anything-goes cliffhangers and shock therapy plots is coming to an end.

Further diminishing their clout is the commissioning of productions by local governments or cultural-tourism bureaus, turning micro-dramas into a new vehicle for regional branding, showcasing ancient towns, dialects, and street foods. Meanwhile, the launch of China’s National Radio and Television Administration’s “micro-drama plus” initiative earlier this year all but certifies the format—portable, visual, and perfectly optimized for the attention economy—as a new tool for top-down influence.

Amid this landscape, Shaanxi Mango, a micro-drama production company based in China’s ancient capital of Xi’an, has carved out its own lane. Its producer, who goes by Yuening, describes their work to TWOC less as “content production” and more as cultural excavation. One of the studio’s flagship projects, Nine Regions, Boundless Realms: A Dream Across Millennia, reworks strands of local history, cultural traditions, and intangible heritage for the bite-sized format.

Meanwhile, other micro-dramas such as Sword Soul, Searching for Love, and First Encounter, draw on specific cultural sources—bronze weaponry, Tang dynasty poetic motifs, and the ritual bell strikes of Xi’an’s Small Wild Goose Pagoda.

As for funding and profit, “Local cultural-tourism bureaus provide essential support,” Yuening tells TWOC. “They coordinate access to heritage sites and cultural institutions, amplify our releases through official channels, and in some cases offer subsidies once a project passes evaluation.”

In addition, in today’s fast-paced world, what begins locally no longer stays local—and micro-dramas are no different. China’s self-invented medium has not only gone global, but is now being touted as a symbol of new cultural confidence. Together with web novels and video games, they form what scholars describe as China’s “new trio” of outbound digital culture. By 2027, researchers estimate that exported web novel titles will surpass 1 million, overseas revenues for web series may exceed 10 billion US dollars, and outbound game profits could climb past 25 billion US dollars.

Han, whose work involves expanding micro-dramas’ reach overseas, frames the format’s scope more bluntly: “So far, the only type that’s proven to work internationally is the CEO-romance genre; vampires and werewolves, which already align with Western cultural DNA, are essentially variations of the same female-oriented fantasy.”

“Everything else,” she adds, “is still largely untested. Western audiences could support many other genres, but Chinese companies haven’t yet found the right entry point or fully grasped Western cultural context—and that’s normal.” Foreign teams can build apps and buy traffic, she says, but they struggle to reproduce the content itself. What powers micro-dramas is the narrative muscle Chinese creators have honed over years: stacking shuangdian or “plot twists,” pacing emotional highs, accelerating tension without losing viewers—skills that creators trained in traditional film-and-TV logic cannot acquire overnight.

Han notes that many Chinese micro-dramas have faced overseas criticism for graphic violence—especially against women. “If you want a hit in the US,” she says, “tell female-led stories about independent women.” For male-oriented dramas, she adds, success comes from action, thrills, and the urge to protect family or homeland—as seen in franchises like Fast & Furious or Spider-Man.

Yet across markets, one pattern holds: micro-dramas have become a narrative inevitability in a social media era defined by fragmentation and emotion. The question then is no longer whether the format is “premium” enough, but rather, as this new storytelling ecosystem takes shape, how will the world learn to live with it, understand it, and ultimately determine where it goes next?

Refined or Flashy: Are China’s Micro-Dramas Really Evolving? is a story from our issue, “New Markets, Young Makers.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.