From encyclopedia to political pamphlet to standard classroom reading: 70 years in the history of China’s bestselling dictionary

“I slew the wrong goose,” a man complained in his letter to the editors of the Xinhua Dictionary.

It was the 1970s, and the man needed to slaughter a male goose from the flock he had raised. Unable to distinguish the male geese from the females, he consulted the Xinhua Dictionary.

“Goose: A kind of poultry,” it read. “The male goose has a yellow bump on its head.”

Satisfied, he trundled off, plucked out a goose matching the description and brought it home for slaughter. Slicing open its stomach, he immediately cursed the dictionary—as the valuable eggs needed to sustain his flock poured out onto the counter.

While the dictionary entry wasn’t entirely wrong, it hadn’t made clear that all geese have a yellow bump on their heads; males just have larger ones. Sympathizing with the man’s complaint, the editors corrected the error in the next edition.

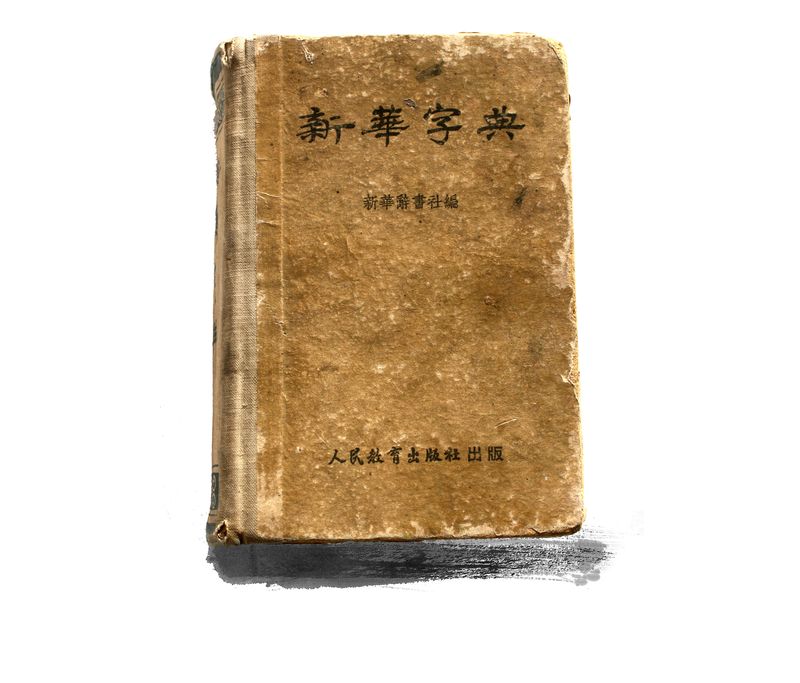

For better or (in the man’s case) worse, the Xinhua Dictionary has been used as an encyclopedia by people across the Chinese mainland since its inception in 1953. Having published its 12th edition as of 2020, the ever-evolving reference work has sold over 400 million copies, a track record bested only by the Bible and a handful of other religious, political and a few literary texts. So what’s a dictionary doing in the upper echelons of China’s all-time best-sellers list?

Like most of the other top-selling texts, the dictionary propagated a world view. When it was first published, the name Xinhua—literally “New China”—bore the hope of a country reborn. Linguists meticulously wrote and edited the content, which was the first to be compiled in Modern Chinese. Their task was made all the more critical because, in the late 1940s, around 80 percent of China’s population was illiterate. In a way, they were defining not just words, but the future character of public knowledge and ways of thinking.

“My family got their first dictionary in the 1960s,” recalls Qing Zhu, who grew up in the countryside of Jiangsu province. “Before that, we turned to the shizi xiansheng (识字先生, literate man) in our village whenever we needed to write anything.” The dearth of knowledge was such that, in some regions, early editions of the dictionary featured illustrations for entries like “pigeon,” “brain” and “umbrella,” and there was even a manual detailing how various chemical fertilizers should be used.

The scholars behind that first edition were certainly patriotic, if not particularly political-minded. That all changed when the Cultural Revolution began in 1966. Copies of the previous year’s edition were stripped of their covers and sold on the cheap, with many carrying a sticker on the first page cautioning readers to adopt a critical approach when consulting them. This curious warning was issued to protect readers from what the government’s Cultural Revolution Propaganda Section described as “capitalist notions smuggled into the dictionary, a lack of class analysis…and conflicts with the current political climate.”

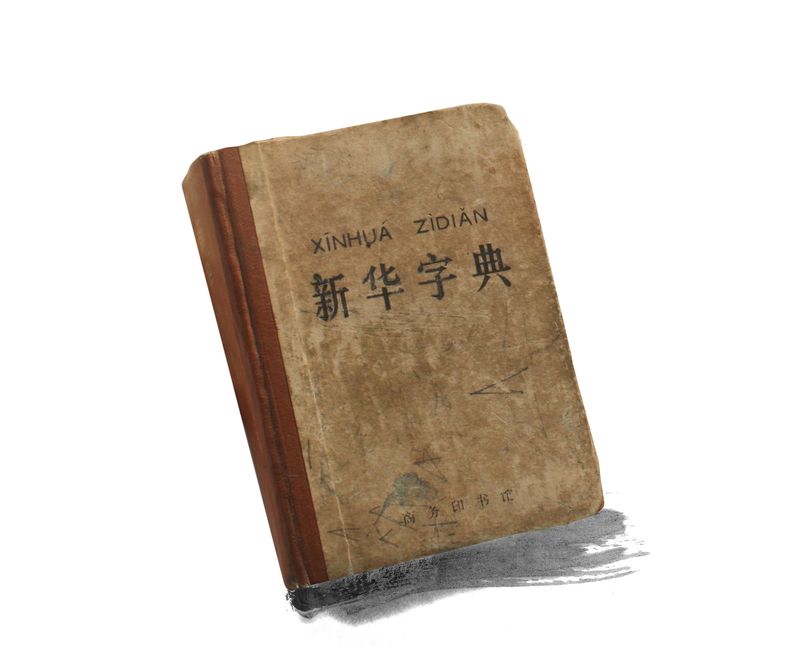

In 1970, when schools re-opened after a three-year closure, the need for a new, more politically correct edition became even more pressing. The 1971 dictionary was originally supposed to include changes to more than 1,000 entries. Fortunately, Premier Zhou Enlai stepped in to directly supervise production, ensuring that in the end only 64 changes were made and the dictionary’s dignity was preserved. Forty-six of Mao’s proclamations were inserted into the final version, with two prominently displayed on the title page. There were also clarifications made to existing entries, which in some cases meant appending explicit Maoist instructions. For example, a sentence used to illustrate the meaning of the character 呼 ( hū, to shout) was changed to “Loudly shout ‘Long live Chairman Mao’.” To explain 翻身 (fānshēn, reversing one’s fate) they used “The working people have reversed their fate and become the masters of society.” The sentence defining 等不及 (děngbùjí, cannot wait to) was previously “I cannot wait to go back home,” but this was changed to “I cannot wait to return to my work station.”

Though today, these definitions read as comically bald propaganda, for readers at the time they were no more political than, say, a love letter; they reflected the way people were speaking and writing. Though its early efforts may have failed the goose farmer, Xinhua succeeded in opening up knowledge and its consequent opportunities to millions.

“I bought my first dictionary in 1971 and still treasure it,” Lu Ye, a woman in her 50s, recalls. “We had no education during the Cultural Revolution, and when the school system returned in 1970, I only knew as many characters as a 10-year-old should, but the dictionary helped me gain entrance to a high school for adults.”

As the country emerged from the Cultural Revolution, people became aware of the difference between the “truths” laid out in the dictionary and the realities of the wider world. A 2011 editorial in China Youth Daily tells the anecdote of a middle-aged Chinese man who, when he went to America for the first time in the 80s, was greatly puzzled—the 1971 edition’s definition of “freedom” had led him to expect a country “dictated by an exploiting class, where the exploiting class has the freedom to exploit the working class and the working class has no freedom to avoid exploitation.” The reality, as we know, was markedly different.

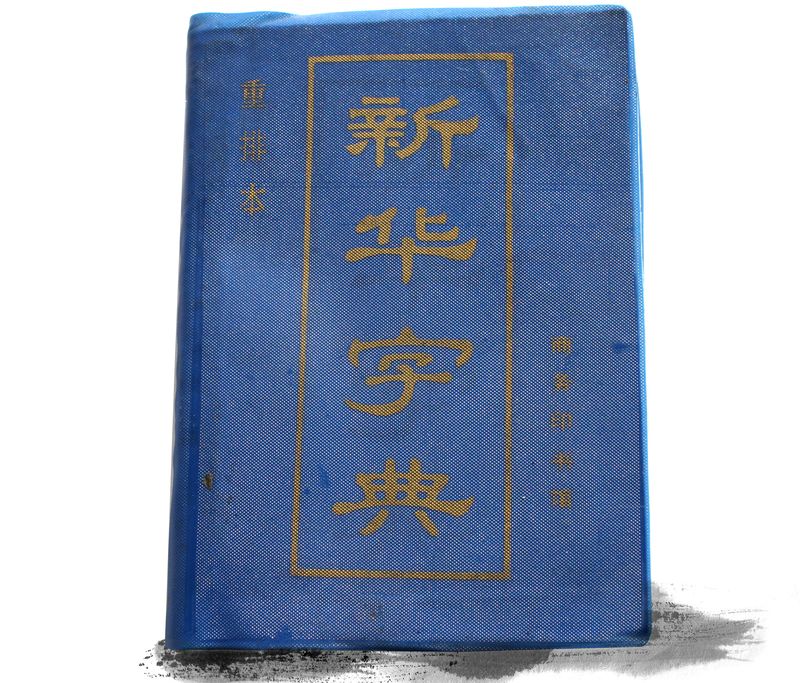

It was hard to erase all traces of that era’s misconceptions in one fell swoop, but Su Peicheng, one of the editors of the 1971 edition, announced to the national press that he and his team “were no longer making political dictionaries.”

As the dictionary became increasingly depoliticized, prostitutes were no longer described as “the outcome of an exploiting institution,” and gambling dropped its tag as “a vice prominent in pre-liberation China.” Meanwhile, other changes signaled unrelated shifts in cultural mindset. While “sturgeon” was once defined as “edible,” later editions provided the slightly more eco-friendly description of “an endangered species.” By the same token, leopards shed their categorization as “wild animals whose fur can be made into clothes.” However, tigers were not so lucky, with “tiger hunting” remaining the illustration for “to hunt” up until the 10th edition.

The dawn of the Economic Reform and Opening Up era heralded a revival for educational resources, and the subsequent influx of thousands of dictionaries has eroded the Xinhua’s stranglehold on the market. The policy also spurred the production of a slew of reference books dealing with specific subject matter, ranging from tea to various fields of academia, all of which further whittled down the Xinhua’s status as the go-to publication for both researchers and the public.

Still, even today the Xinhua Dictionary remains the standard reference for students learning characters, and the one book that first graders are told to buy it before they start school. Every year, primary schools all over the country host intensely competitive word-search competitions, which challenge kids to look up the definitions of random words in the fastest possible time.

One curious result of this childhood love affair with the Xinhua text is a marked similarity in the way Chinese children speak and, to a certain extent, think. “All [China’s] primary school compositions are similar and standardized,” a 2010 editorial in Guangzhou’s Southern Weekly newspaper claimed. “For example, if [Chinese children] write about a spring expedition, the sky is invariably ‘cloudless for ten thousand miles’ and we’ll undoubtedly ‘sing and dance’ on our way,” both expressions sourced from the dictionary. Moreover, the writer professes that upon seeing the national flag, he and his friends are almost helpless to resist thinking of the dictionary reference, “It’s dyed by martyrs’ blood.”

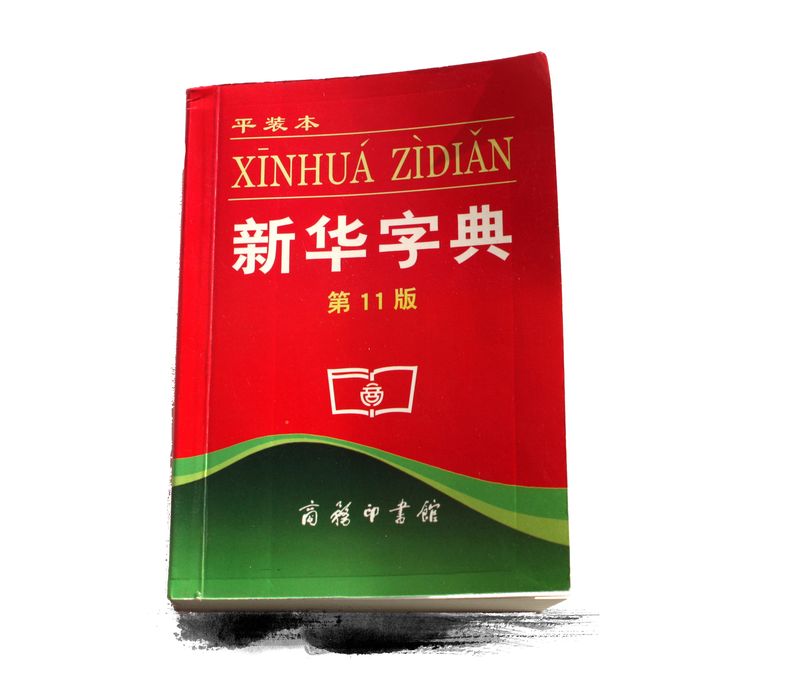

The illustrious tome’s 11th edition was published in 2011, and, with it, the standardization of a raft of new words and explanations. The text that once featured illustrations of an umbrella now uses mobile phones to illustrate the meaning of “handy, portable” (手 shǒu). But in a tacit acknowledgement of the proliferation of alternative sources of information, the editors have scrapped a whole host of definitions under the proviso that people don’t need a dictionary to help understand them. Entries like “kerosene,” “motor” and “secretary” have been consigned to the scrapheap. Instead, the dictionary boasts a heavier focus on the current usage of words, and the evolution of new meanings from old favorites.

For such a traditionally conservative publication, the 11th edition also sparked controversy for its inclusion of words recently made popular by tabloid news titles, online forums and personal blogs. “Gate” (门 mén) is interpreted as a “scandalous event,” based on the infamous 2008 sex photo scandal involving Hong Kong actor Edison Chen. Almost overnight, headlines almost uniformly began referring to the incident as “sex photo gate,” itself based on the 1972 Watergate Scandal in the US. After that, much as in English, the suffix was appended to a series of scandalous events. Another influence of English on Chinese was acknowledged with the term 晒 (shài, to dry something under the sun), listed as having the second meaning “to share” due to the similarity in pronunciation with the English word.

Recent cultural phenomena have also been addressed via the inclusion of entries like “house slave” (房奴 fáng nú), a metaphor for people forced to slave away at their jobs in order to afford loans for an apartment. Until the latest edition, the only explanation of “slave” had been: “People who had no freedom and were oppressed, exploited, and used as labor by the exploiting class in the pre-Liberation China.”

These concessions caused a stir in academic circles, with some concerned that the more playful tone was inappropriate and the new words would not have the staying power to embed themselves permanently in the language. When challenged to defend the additions, dictionary compiler Han Jingti seemed unconcerned. “This is what we decided after we researched the frequency of [the words’] appearance in various media,” he said. “After all, linguists are only recorders and researchers of the language, not its police.”

1971 Working Class

- 工人阶级 -

“The Working Class represents the most advanced productive force. It has the greatest foresight. It is the greatest class in human history.

1971 Palace

- 殿 -

“Tall, stately buildings. Archaically used to refer to places where emperors issued orders or religious people worshipped gods.”

1953 Otter

-水獭 -

“ A species of wild animal that lives near water. It can swim and feeds on fish. Its brown fur, which can be made into scarves and hats, is very valuable.”

This is a story from our archives. It was originally published in 2012 in our issue “How the TV Stole Spring Festival,” and has been lightly edited and updated. Check out our online store for more issues you can buy!