A look back at the past of one of Jilin’s most important industries shows just how far the province has come

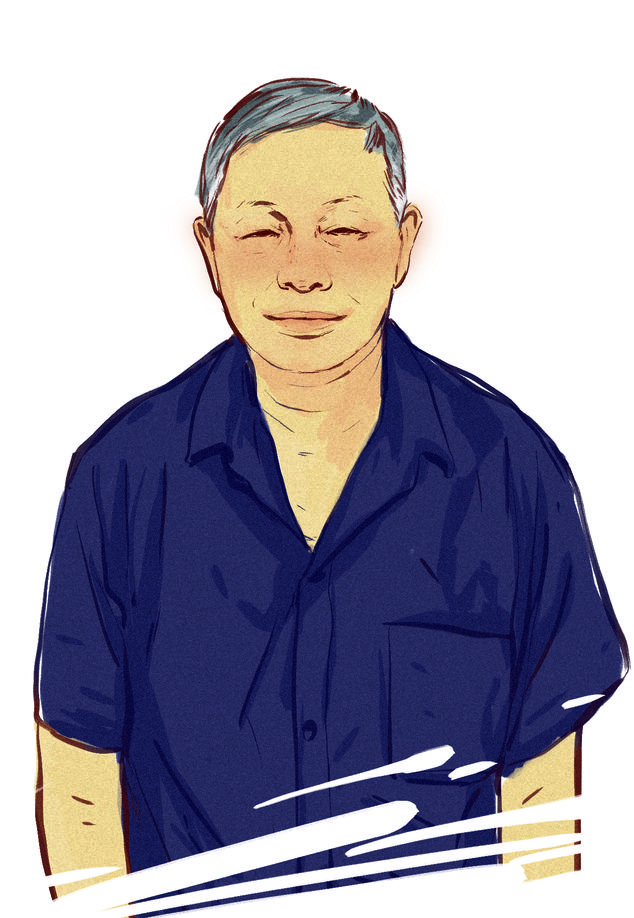

At age 78, having retired from 40 years of assembling and painting trucks at the First Automobile Works (FAW, 第一汽车制造厂) from 1964 to 2004, energy still courses out of Jiang Renzhong when talking about his old job. His eyes light up, and his words are infused with a passion that raises the seemingly humdrum routine to a show of strength and artistry. To him, manual spray painting is a misunderstood craft: “It took me several months to get it right,” he says passionately from across his kitchen table in a Changchun housing compound, with a twinkle in his eye. “It’s precise finger work…if you put too much pressure [on the sprayer’s trigger] the paint will go everywhere; too light and it won’t spray properly.”

The difficult working environment didn’t help. Jiang and his colleagues labored in a warehouse at over 30 degrees Celsius, wearing two gauze face masks dipped in water to protect themselves from the paint’s toxic fumes, and took an hour off for each hour they worked for additional protection. “It was fine for those with strong lungs, but not everyone was capable of working in those conditions, which were very demanding,” Jiang says, but the demanding pace made it easier. An even, glossy coating had to be applied to the vehicle in just one minute while the parts moved continuously on chains across the factory floor, all while wasting as little paint as possible.

In the 20th century, FAW was of national importance amid China’s early efforts at industrialization, sharing the responsibility of the wider northeastern industrial area to lift the country out of an agrarian economy.

The plant was a key part of the China’s first Five-Year Plan in 1953, constantly in the gaze of the public and government alike. Chairman Mao visited FAW in 1958, christening the company’s first vehicle Jiefang (“Liberation”) trucks. These were the trucks Jiang worked on when he first arrived on the job in 1964, tasked with meeting production quotas of 2,000 chassis per month.

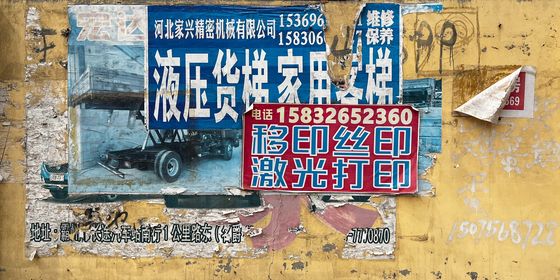

When first produced in 1956 at the FAW plant in Changchun on Soviet designs, the Jiefang CA10 was the New China’s first-ever domestically manufactured vehicle, and—before Japanese trucks entered the market in the 1980s—a street-scene staple of the pre-reform years.

FAW was a giant of the region, its equipment state of the art. Jiang remembers the brand being a source of pride: “Even the name alone would make people want to apply for a job there.”

Beyond production, the importance of FAW meant it was expected to demonstrate how a model socialist factory could work. The salary was, in general, higher than in other local factories, and the benefits more extensive. “As FAW was a big factory, it was incomparable to working life in little ones,” says Jiang. An FAW worker’s job was a so-called “iron rice bowl”: a guaranteed job for life, with a full retirement package. The company took care of every element of a worker’s life—providing on-site hospitals to treat them when they were sick, schools to educate their children, and housing for their families. Workers were even provided with hot water for showers, incredibly rare for most factories of the time.

Whole families would be employed by the company (and still are, as Jiang’s son also works at the plant). The bond of workers from the same family employed by the same company over generations is known as “sharing the same fate.” Even today, 78 percent of Changchun’s population is directly involved in the automobile industry according to news site The Paper. The car industry is the beating heart of the economy of Jilin’s capital.

Indeed, work culture was so geared toward workers that being transferred to officialdom was a strange concept, not a promotion but a letdown. “I never thought about doing other jobs, I just wanted to do my own bit, to be a screw in the bigger machine and to do my job well,” says Jiang of the sense of pride and status in being a worker.

In 1964, the pay was 39.50 RMB per month, “at that time it was a great deal of money.” It was indeed—a bottle of beer was only less than 1 yuan at the time, while the most expensive thing Jiang owned was a bicycle, at 100 yuan. By 2004 when he retired, the salary was 2,000 to 3,000 yuan per month—still higher than that of private factories in the area.

But it wasn’t all milk and honey. The marketization of the economy forced many state-owned companies to reform and redevelop. Being so-called “gloriously laid off” at that time became a running problem across the northeast. FAW laid off 50,000 to 60,000 workers in 1990 according to Jiang; exams and tests decided who stayed and who went during the layoffs. Some other staff were subcontracted in from small private factories.

Jiang and his family have witnessed a process of evolution. When Jiang started out, FAW’s annual production figure was 60,000 vehicles. Before he retired, this had become 200,000 to 300,000 a year thanks to mechanization. In 2020, FAW was reaching sales figures of 3.7 million vehicles a year, and producing models that run only on electricity. The times have indeed changed.

From China’s First Sedan to Luxury Limousines

The humble origins of Chinese car-making can be glimpsed in the Hongqi Culture Exhibition Hall (红旗文化展馆) in Changchun.

“China’s First Sedan,” the Dongfeng CA71, is a small red car from 1958 whose rear brake lights are shaped like a pair of red lanterns, while a gold dragon flies down the hood. Chairman Mao Zedong tried the car out in the gardens of the central government compound at Zhongnanhai that same year, and expressed that it was such a pleasant experience to ride in China’s first domestically produced sedan.

Today, Jilin’s own First Automobile Works is a burgeoning manufacturing giant, reaching 87th place on the 2020 Fortune Global 500 list. But it’s the company’s luxury car brand, Hongqi (“Red Flag”), that has been FAW’s real success story. Domestic sales doubled from 2019 to 2020 with 200,000 deliveries, while sales for both January and February of 2021 broke records by rising 158 and 247 percent respectively from sales in the same months in 2020.

These figures are unsurprising, given that Hongqi is symbolic of the nation’s homegrown automotive industry. Right after the birth of the CA71, FAW was tasked with the design and manufacture of a larger model for use by national leaders. Having never seen an actual luxury sedan before, FAW designers borrowed an old Chrysler Imperial from the Jilin University of Technology as a reference. The line was officially named Hongqi by Wu De, secretary of the CPC’s Jilin provincial committee at the time, during the celebration of its completion.

It was the next model, the upgraded CA770, a three-row luxury sedan built in 1966, that helped Hongqi cement itself as the go-to vehicle for ferrying national leaders and visiting foreign dignitaries. The most iconic Hongqi photos are those of various top leaders being driven through military parades while standing in classic black sedans, with their torsos protruding out of the open sunroofs allowing them to inspect rows of uniformed troops.

In 2015, the government announced the “Made in China 2025” initiative, aiming to revitalize Chinese brands. To cater to China’s growing number of wealthy consumers, Hongqi wheeled out its L7 and L5 luxury limousines for public purchase at the 2016 Shanghai and Beijing Motor Shows, respectively. Marketed as a “classic limousine,” the L5 harks back to Hongqi’s original CA770, and contains many traditional twists. The doors are inlaid with jade, and the dashboard with dappled wood inspired by the curves of the eaves of ancient Chinese buildings. It’s a classic company reminding consumers of the value and prestige of all things made in China.

Excerpt taken from Jilin: Land of Mystery, TWOC’s new guide to China’s northeastern province. Available now in our store!