These charitable figures from ancient China didn’t forget to give back when they got rich

Last week, after President Xi Jinping encouraged high-earners to give back to society in order for China to achieve “common prosperity,” the country’s biggest companies fell over each other to pledge to charitable causes. Tencent and Alibaba both announced 50 billion RMB donations to various foundations, e-commerce platform Pinduoduo promised to give away 10 billion RMB to charitable causes, and Wang Xing, the founder of Meituan, transferred shares worth nearly 13 billion RMB to philanthropic projects.

But while some of modern China’s super-rich are only now being compelled to give back, it’s been a tradition rooted in Confucian teaching throughout Chinese history for those with wealth to offer charity. As the philosopher Mencius put it: “In poverty, one should still hold himself to a high standard; and when prosperous, one should contribute to the well-being of all (穷则独善其身,达则兼善天下).” Guided by such doctrines, many philanthropists emerged throughout history. Generous with their money, caring for others, and even devoting their lives to charity, some of their stories are still cited today as an example of the embodiment of benevolence.

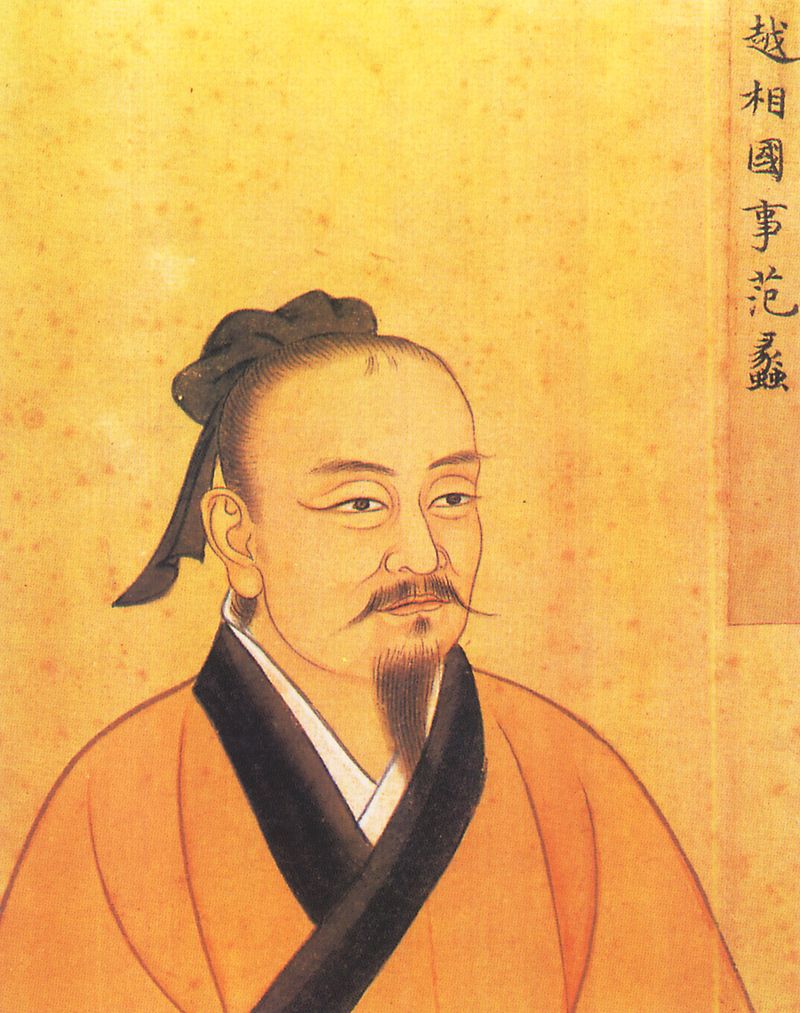

Fan Li gives three fortunes away

Fan Li (范蠡), a military strategist and politician from the Spring and Autumn period (770 – 476 BCE), is best known for helping Gou Jian (勾践), the king of the State of Yue, to conquer the State of Wu and become one of the “Five Hegemons” of the era. He is also remembered for his romance with Xi Shi (西施), one of the Four Beauties of ancient China. But Fan’s success as a businessman and generosity as a philanthropist are underappreciated. According to the Records of the Grand Historian (《史记》), compiled during the Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE), Fan accumulated wealth of 1,000 taels of gold on three separate occasions, and gave most of it away each time.

According to the Records, soon after assisting Gou Jian destroy the State of Wu, Fan resigned from his post. Before he left Yue territory, Fan distributed the majority of the wealth he had made as a high-ranking official to the local populace.

Fan moved to the State of Qi, where he lived a quiet life under the mysterious name Chiyi Zipi (鸱夷子皮), which was a kind of leather bag. He made a living as a trader with his sons and soon amassed another huge fortune, becoming the richest person in the state. Fan was said to be such a talented and innovative businessman that he made money even when he sold boats when the river ran dry and carts when the roads flowed with water. He cared about people in his neighborhood, and often helped them with his own money. Soon, word of Fan’s kindness, and his business acumen, reached the king of Qi, who hired him as his prime minister.

But three years later Fan quit his job again, and before he left the Qi capital, Linzi (part of today’s Zibo in Shandong), he gave all his wealth to his friends and other residents of the city. This time, Fan went to the impoverished Tao area (today’s Dingtao district of Heze city in Shandong province), and soon accumulated another pile of 1,000 taels of gold from business. Anointing himself as the Duke of Taozhu (陶朱公), Fan gave money to local residents and taught them business skills. His reputation spread far, and after his death, people even began to worship him as a “God of Wealth.” Meanwhile, the term 陶朱 also became a byword for extraordinarily rich people, and is still in use today.

Li Ying makes a sweet donation

Li Ying (李英), also known as Li Wu (李五), was a rich sugar merchant from the Minnan region (part of today’s Fujian province) during the Ming dynasty (1368 – 1644). Li used the most advanced refinement techniques and his sugar became renowned for its high quality. It was known as Fengchi sugar.

According to the Book of Min (《闽书》), a historical record completed in the Ming dynasty, and The Chronicle of Quanzhou (《泉州府志》), published during the Qing dynasty (1616 – 1911), Li contributed generously to local charity work. He funded reinforcement of the Luoyang Bridge, a vital thoroughfare in Quanzhou that used to become impassable at high-tide. Li also contributed to rebuilding the Song dynasty’s (960 – 1279) irrigation and flood defense system at Liulipo in Quanzhou, which ensured water for crops and protected from flooding for generations. A stone tablet commemorating Li still stands next to the Luoyang Bridge today.

But Li’s most famous charitable deed came during a pandemic. In 1444, Li was selling his sugar in Yinxian county, Zhejiang province, when a vicious plague broke out in the region. Somehow, rumors spread that eating Li's Fengchi sugar could protect against the disease. With residents rushing to buy the sugar, the price rocketed.

Instead of profiting from the extraordinary demand, Li offered his sugar to the frightened residents for free. To make his supplies last longer, Li’s poured sugar into a well and invite residents to collect the sugar water.

Before long, the plague was brought under control. Though it’s doubtful that Fengchi sugar played a role in warding off the disease, the residents were convinced Li’s generosity had saved them. The well was renamed “Benefactor Li Wu’s Well,” and it still exists today in the Yinzhou district of Ningbo city.

Fan Zhongyan gives up his house to build a school

Fan Zhongyan (范仲淹) was a famous politician and scholar who lived during the Song dynasty, but his legacy lives on today. Every Chinese child learns to recite his essay “Memorial to Yueyang Tower (《岳阳楼记》),” and all know the line: “One should be the first to worry for the future of the state and the last to claim his share of happiness (先天下之忧而忧,后天下之乐而乐).” Fan lived up to his words.

According to A Chronicle of Fan Zhongyan’s Life (《范文正公年谱》), a biography finished after Fan’s death, he led a frugal life even as a high-ranking government official. He saved up nearly all his money and eventually decided to purchase nearly 1,000 mu (approximately 0.07 hectares) of farmland in the suburbs of Suzhou, his hometown. Every cent he made from the land went to helping the poor. Fan’s farm became known as the “chivalrous fields (义田).”

In 1035, Fan purchased more land in Suzhou, and built a house there for his own family. When the house was finished, Fan hired a feng shui expert to inspect the property. The expert was amazed, and claimed the feng shui was so perfect that anyone who lived there would produce generation after generation of government officials. On hearing this, Fan proclaimed: “I prefer to have all people under heaven be educated here rather than enjoy the luck alone. That way, the luck will be endless (吾家有其贵,孰若天下之士咸教育于此,贵将无已焉).”

Fan abandoned his plans to live in his new house, and instead paid for the construction of a school on those grounds. His generosity attracted some of the best scholars of the time to Suzhou to become teachers, and contributed to the city’s reputation as a one with the best education system in the country. Many other wealthy Suzhou residents followed Fan’s example, and the school later become today’s Suzhou Middle School.

Wu Xun begs money to fund education

Compared with Fan Li and Fan Zhongyan, Wu Xun (武训) from the Qing dynasty, was a very different kind of philanthropist—he was neither a scholar nor an official, but a beggar.

Born into a poor family, Wu was originally named “Wu Seven (武七),” because he was the seventh child of his family. His father died when he was a young boy, and his family couldn’t afford to get him an education. As a teenager, Wu became a manual laborer to survive, but his bosses took advantage of his illiteracy to swindle him out of wages. Instead of being disheartened, Wu decided to devote his life to promoting universal education.

Without a decent income, Wu was left to beg for money to fund his cause. From the age of 21, he spent every day begging in the streets, and did odd jobs at night. He traveled vast distances to collect alms, roaming through Shandong, Hebei, Henan, and Jiangsu while spending virtually nothing. Eventually, Wu amassed a fortune, but without a fixed residence for storing his money, he asked a reputable scholar surnamed Yang to care for his savings. Deeply moved by Wu's mission, Yang not only agreed to take care of Wu’s money, but began to assist him in promoting education.

Wu used his money to buy land and make loans to others. Gradually, he became a successful money lender and landlord. In 1888, 29 years after he began begging, Wu founded his first academy in Shandong, where students could learn for free. In 1890 and 1896, Wu constructed two more academies in Hebei and Shandong province. His acts of kindness were reported to the imperial court, and as a reward, Wu was bestowed with the name “训,” meaning “teach” or “educate.”

Wu died at the age of 58 in his academy in Shandong. But his deeds are not forgotten, and his tomb and memorial hall are located in the city of Liaocheng. They have been restored twice, in 1937 and 1989.