Too short to teach? TWOC looks at discrimination in the job market, from hometowns to star signs

It’s not easy to find a good job today. Apart from fierce competition, rampant employee stereotyping and weak anti-discrimination laws means that almost anything could become a job-seeker’s Achilles’ Heel: Birthplace, gender, education, age, marital status, appearance, even star sign.

As millions of graduates jump into the job market this summer, let’s look various types of discrimination they might experience.

Provincial priorities

On July 5, Weibo user @暴躁的北京小娘们 applied for a job at the Beijing branch of Alibaba’s “New Retail” outlet Hema and was turned away by a Mr. Tian, because “Beijingers are rich and we can’t afford them, so the company doesn’t hire Beijingers as a rule.”

As outrage grew, Hema responded that the company has never discriminates by region, and Beijingers account for 22 percent of its workforce. Recruitment manager “Mr. Tian,” on the other hand, was only a “part-time employee” of Hema’s sub-contracted recruitment company Liwei (力伟). Next day, Hema apologized again and suspended its cooperation with Liwei.

Netizens, though, seemed to find this concession unnecessary:

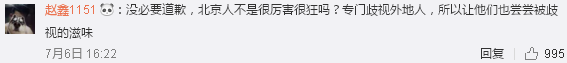

No need to apologize. Beijingers are conceited and arrogant, and look down upon non-Beijingers. Let them know what discrimination feels like

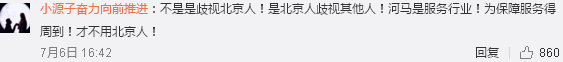

That is not discrimination against Beijingers. Beijingers are the ones who discriminate against people. As Hema is a service provider, in order to provide excellent service, it must not employ Beijingers

I agree. Beijingers are so rich, they don’t need to work at all

Regional discrimination is common in China’s job market; unlike Mr. Tian, few recruiters deign to explain why. On May 9, an email was leaked from iQIYI‘s HR department, suggesting that Henanese applicants for their internship program should be scrutinized (and excluded) as much as possible.

A few days later, a similar case was reported at Meituan, whose employees received a bizarre recruitment notice banning the following candidates: (1) those with ugly resumes; (2) holders of postgraduate degrees; (3) Volkswagen drivers; (4) those who believe in Traditional Chinese medicine; and (5) anyone from northeast China and the Yellow River floodplain areas (including parts of Shandong, Anhui, and Jiangsu provinces).

Major discrimination

Every year, students and parents go to new extremes stressing over the gaokao—but their actions start to seem reasonable when one looks at the ways recruiters judge applicants based on university rankings and choice of majors.

In October 2017, a Suning recruitment manager spoke at the Guangdong University of Technology (GDUT), saying the company only recruits management trainees from the Ministry of Education’s prestigious Project 985 and 211 universities. (He neglected to note that GDUT is part of neither project)

According to The Paper, Xiaomi’s recruitment manager Mr. Qin even told an audience at Zhengzhou University in September 2017 that “Japanese majors may leave the event immediately” and suggested they may “switch to film studies.”

Height of absurdity

Earlier this year, a recent graduate from Shaanxi Normal University in northwestern China was told that she was “too short” to be a teacher.

According to CNWest.com, Ms. Li (pseudonym) enrolled at Shaanxi Normal University on a full scholarship in 2014, majoring in English. When she applied for a teaching license before graduating, she was told she fell short of the “height requirement”—Li is 140 centimeters tall but, in 2009, an obscure notice issued by the Shaanxi Health and Family Planning Commission inexplicably stipulated a minimum height of 155 centimeters for male and 150 centimeters for female teachers in the province.

In the public outcry that followed, the Shaanxi Educational Department promised to review the rule and abolish the height requirement by next year. A few other provinces, including Sichuan and Guangdong, have already abolished height and weight requirements for public teachers.

Stars struck

People can’t choose when they’re born, but many Chinese bosses like to choose employees by their astrological signs, usually based on pseudo-scientific explanations of zodiac-influenced personality types.

In 2015, Youzhu, an online interior-design platform wrote in its recruitment ads that “priority will be given to Virgos.”

In 2016, the Guangzhou Daily reported that Qingdao financial company also only wanted Virgos at a job fair. The HR director told the paper that, among all 12 risk managers in the company, 11 were Virgos; based on their 15 years of totally scientific observation, Virgos were therefore best at controlling risk.

For Virgos, often stereotyped on dating sites as control freaks who make terrible partners, this may be good news, finally; not so good news, perhaps, for anyone working under them.