Chinese author Yi Bei explores roommate relations in a crowded Beijing apartment

After Mr. Lou moved in, the apartment was full.

The east-facing room, where a couple named Duan lived, was the largest. The wife was pregnant. Duan kept saying they were going to move out, that environment was so important to raising a child, that our place was so crowded, any child who grew up there was going to be a sissy…

But he’d been talking about it for six months and still hadn’t moved. The wife got laid off; she was full-time pregnant. With the little money Duan earned, once you subtract the rent, there was barely enough for milk powder; how would he get money for another apartment? There were two small south-facing rooms. I live in one; divorced, single. I was an early bird and still no worm—married at 22, now a super-leftover lady at 30. I’m even more leftover than leftovers, with no children but a record. Though it’s not so bad as having a “past,” I still can’t compete with those normal women getting married for the first time.

I play the face game. Though I’m just getting by as a dental hygienist—holding the vacuum wand to siphon away patients’ saliva, handing the dentist the pliers, or drill, or whatever—I tell people that I “do surgery.” In the medical field, surgeons have the most prestige, and I have to have some face. It’s important in a big city, where people want to look at you and see a shiny surface. “Oh, Hu Mingzhu, she’s doing alright: nice job, good looks, good character.” Those are my bargaining chips for re-marriage.

In the room next to me was a middle-aged woman of about 50, surname Men. I heard that she moved to the city with her daughter during her school years. Now, her daughter has married a rich local, but “Aunt Men” hasn’t moved in with the in-laws. She’d like to have all the generations under one roof, but their apartment is small and she’s ashamed to ask. She’d like to be an involved grandmother, but it’s not that easy. The in-laws want to care for the baby, so where would Auntie Men fit in?

So now, the old woman thinks, maybe she could find a partner, someone simple, as long as he had an apartment and was healthy. She was afraid the city folks would look down on her, so she’d been working hard at learning to do her makeup. Sometimes she’d ask me this or that: How to do her eyeliner, the difference between foundation and face powder, whether or not she should use primer on top of BB cream, and the like. Although when it came to makeup I was merely a dabbler, I was flattered to be asked, despite the inconvenience.

At 8:30 at night, Aunt Men burst into my room without knocking. I was doing a moisturizing mask, so my face was covered in green mud. “Ah, Mingzhu.” Now she was sitting on my bed, gripping my hand. “What’s that new guy’s background? Who found him?”

I closed my eyes and pursed my lips, so I wouldn’t get wrinkles. “He said the guy here before, Zhang, found him, since he had to move in a hurry. So he hooked Lou up with us to fill his place. He pays 1,500 RMB a month, which is decent.”

Aunt Men paused for a second. “What is his name? Where is he from? How old is he? What does he do? Have you asked him these things?”

With my eyes closed, I had no idea what expression she wore, but her eyebrows were probably raised and lips pursed with great effort, ready to confront class enemies. I wanted to say: Old lady, why do you care? As long as he pays rent on time, doesn’t have any infectious diseases, doesn’t break the law, why the hell do you care what he does? Are you running a census? I had, however, to stay on good terms with my housemates, so all I could say was “I hear he’s a decent guy, and doesn’t seem like a criminal from the looks of him.”

Aunt Men saw me open my eyes, and scooted closer, offering her opinion: “One can’t judge a man by his looks! How can we know what lurks in his heart?” OK, OK. As a man cannot be known by his looks, so the sea cannot be measured by a bucket. Well, no matter what, Lou seemed to be a decent guy with his things in order. On his second day, he invited us out for dinner: Han Li Xuan Barbecue—not high-end, but a nice gesture.

Aunt Men, Duan, and the wife had about 30 plates of streaky pork, bacon, beef, and chicken, and ran the census on Lou the whole time. His full name was Lou Qingbo, 28 (though he looked younger, maybe 23 or 24, clean with a small face). He held a master’s degree (not sure from exactly where, but it was in Beijing). He was from Zhejiang, and worked for some company (not clear if state-run, multinational, or private). He made about 5,000 RMB a month, and was single.

During the entire meal, Lou more or less just answered questions and didn’t say much else. He liked to keep his gaze low, and would occasionally smile shyly. Aunt Men and Duan’s wife were the opposite, maybe as the meat and alcohol had set them alight. They’d suddenly burst out laughing. Thankfully the restaurant was noisy, or Duan would have died from embarrassment. Whenever things began getting awkward, Lou would raise his glass, and Duan’s shame would melt away.

Everyone had to admit Lou’s moving in eased our economic burdens. Each of us had to pay at least 350 less per month in rent and, we all quickly discovered, he was quite generous. For instance, at Christmas, his company gave out a large box of Jiangxi oranges, which he put in the common area, telling everyone to take as many as they wanted. They actually did: Aunt Men took a few good kilos when she went to see her daughter, and Duan’s wife, at home all the day, would take one to her room whenever she felt like it. Of course it was “for the baby, who needed Vitamin C.” I didn’t get to have a single one before they were all gone.

Lou didn’t seem to mind. At New Year’s, he bought glutinous rice balls, which everyone was more than happy to accept. He rarely initiated conversation, but made a beeline for his room whenever he got home. The only time he made an appearance was for dinner. He liked to watch entertainment shows on TV, standing in front of the set, a bowl of noodles in hands, laughing as he ate. When he’d finished, he’d head straight back into his room. I didn’t know what he was doing in there; only that the light seeping from the crack under his door didn’t go out until quite late at night.

Things were peaceful enough. The New Year came and went, and Duan’s wife’s belly continued to swell. She lay around all day, never going out, fantasizing about how the child was going to do great things and make her proud. I was still single, and so was Aunt Men. She was worse off than me; the old bachelors looked down on her lack of an apartment or Beijing residence permit.

I was in the bathroom looking in the mirror, drawing on my stupidly thin eyebrows, when she barged in, mumbling how sorry she was, but she just couldn’t hold it anymore, removing her trousers as she ran. As soon as her rear touched the toilet seat, I heard a little waterfall. I furrowed my brow and stared into the mirror; I wasn’t on good enough terms with this woman to have to listen to her pee.

I looked at her through the mirror. She was wearing makeup—red lipstick, eyebrows drawn on a bit crooked, and she even contoured her nose! What decade was this look from? Not a good way to make an impression with your date. “Mingzhu, Auntie is someone who has experience. Work shouldn’t be your primary concern—you have to seize the opportunity, find a good person to marry. Don’t end up like me, old and passed over. Just think of the choices I had back then!” Aunt Men was lost in her memories; she didn’t know I was divorced. “OK, I get it!” I couldn’t help but cut her off. “Of course, there’s always an element of luck.”

“Sometimes you have to make your own luck,” Aunt Men shot back. “Look at Fan Bingbing, and all that’s she’s done.” I didn’t know what to make of all this nonsense. Aunt Men continued: “If you gotta seize opportunities. If there aren’t any opportunities, make one.” “An opportunity?” I asked. Men smirked. “I think you and Lou are a good match.” Me and Lou? Never thought of it. We were hardly close; I’d spoken less than 10 sentences to him. We both left in the morning, came home at night, and did our own things. Still, from what my first marriage taught me, I thought Lou might be quite a reliable guy: straightforward, not overly talkative, a doer.

However, I hadn’t harbored any desire for more contact with him. I’d had a boyfriend, a Taiwanese guy, also formerly married. He was older, but I felt I had to be practical at my age. Based on my observations, Lou’s love life was also calm and uneventful.

At the Spring Festival, on the 29th day of the last lunar month, I opened the door and saw that Lou standing in the common area, a bowl of instant noodles in his hand. He wasn’t smiling, and I made a few quick guesses. Aunt Men and the Duans had already returned to their hometowns, and even Mr. Taiwan had gone back to his little island. I took off my heels and put down my bag, putting on a nonchalant air: “Oh, so you didn’t go home?”

Lou turned his head towards me, a half a noodle still hanging from his lips. “No.” I suddenly felt emboldened, and joked: “Well, that’s great! I’m not going back either, so we can spend the festival together.” Lou spoke: “That…that’s not necessary.” I felt I’d said the wrong thing. “I didn’t mean it that way.” I laughed and returned to my room without another word.

The guy was just putting it on, even with me. It’s the Spring Festival and he’s not going home. We all know what that’s about—you don’t want to deal with your relatives, pushing you to get married, and your friends asking you how much you make in Beijing, if you have an apartment, a car, and a marriage license; the kids are like a swarm of locusts, everyone piling it on everyone. OK then, we’ll do our own thing. I can have my own Spring Festival.

The next day, Lou wasn’t home. My ex-husband called, trying to provoke me. He knew I wasn’t going home. I snapped, “Don’t bother me and my boyfriend!” My ex was getting ready to say something, but I savagely smashed the “end call” button. I wanted to cry but couldn’t, because I was also quite hungry. I had to go buy some dumplings, but the supermarket was closed. Then I remembered that, not far from my building, there was a 24-hour convenience store.

As I headed back with a bag of pork and cabbage dumplings, my mother called. She didn’t know about the divorce, and asked how Spring Festival was at my in-laws’. I held back tears, saying we’d just finished eating and everyone was having a blast. “Hey, listen, they’re setting off firecrackers outside.” As I spoke, I started to cry. I wanted to go home, anywhere, even if it was just some random rented apartment. I started to prepare the dumplings—if I couldn’t finish them all, well, then I couldn’t. Enveloped in a cloud of white steam, I heard Lou come back. “Let’s eat together!” I said, trying to sound upbeat.

This time, Lou humored me, and walked into the kitchen, helping me pour cold water into the wok. “Add cold water three times, and they’ll be done.” “Well, my husb—” I realized I said too much, and cut myself off and smiled, “I mean, my father, he always said you had to add water like this.” Lou didn’t say anything. I saw that his eyes were a bit red, and hastily asked, “Is the steam getting in your eyes? Stand farther away.”

My friendly white lie helped ease the discomfort. Lou assured me that it was nothing, that he was just touched. Touched? I started at him, but didn’t know where to start. “At this time, at this place, who else can be there for me, huh?” My eyes felt a little wet too, and couldn’t help but open up. “Actually, please don’t tell anyone, but I’ve been married and divorced.” Lou looked at me, almost smiling through tears, and said: “Who cares? Isn’t that in the past?” I asked him: “What about you?” He laughed bitterly. “Me? My story is so bland, it’s not even worth telling.”

OK, if you don’t want to talk about it, I won’t ask. The world is boundless. Me, a super-leftover woman of 30, and a young man who couldn’t return home for the Lunar New Year, a lonely non-couple, eating dumplings together as if nothing was amiss, and skipping the CCTV Spring Festival Gala, instead watching a super-lame film, The Amazing Spider-Man, together. I’d seen it before, but this time it didn’t seem so bad, maybe because the previous time I’d seen it alone. It turns out, what I’m most afraid of is being alone.

In the blink of an eye, we were all back at work. Like the crows on tree branches on the side of the road in winter, the Duans appeared right on time. Aunt Men came back two days later. I picked up the vacuum wand again, and stood by the dentist, siphoning patients’ saliva. Sometimes when I wasn’t in a great mood, I’d cling to the tiny bit of power I had, chastising our patients: From now on you can’t speak, just nod your head. Be careful not to choke on your spit. Ah, that was just how life was. Most of the time, other people step on you, so sometimes you just have to do a tiny bit of stepping yourself.

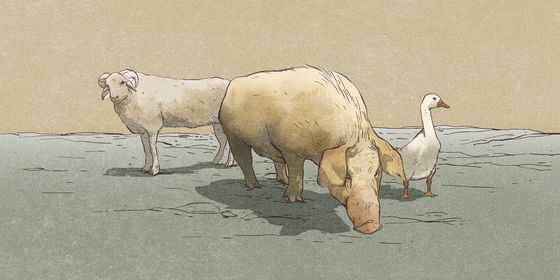

Not long after, Lou suddenly bought a dog, a white Bichon Frise. Even though it looked obedient, playful, and cute, when Aunt Men came in, it started to bark. One night, when Lou just got back home, Aunt Men pressed him into a chair. I sat by the dining table, while Aunt Men and the Duan couple watched from the sofa.

Lou asked Aunt Men what was up, and she, still smiling, pointing at Duan’s wife’s belly. “Now, Lou, we all live together; you can’t be too selfish.” Lou’s face suddenly reddened as he sat under the fluorescent light, his neck illuminated as he lowered his head.

Duan’s wife spoke: “Lou, so sorry, it’s not that you can’t have a dog, but look at my belly, look how large it is. I don’t mind, but I’m worried that once the baby’s born, something will go wrong with the dog. How would I face my husband’s family?”

Duan didn’t say anything, but thumbed a cigarette out the packet which his wife then reached over and smacked away. I understood Lou’s position. He was lonely, and a dog would help him, and maybe he saw a bit of himself in the little Bichon, also alone in a big city with nobody to rely on—at least they’d have each other.

I cleared my throat: “I’m not a huge fan of having a dog living here, but you’re going to have the kid soon, so I don’t think it’ll be a problem. People say dogs are unclean, but I’ve watched it a few days and I think this Bichon is fine, it always does its business in that coal box; let’s let Lou keep it a few more days and observe.” Lou spoke haltingly: “It’s a good dog, it listens to me.”

Duan slammed his cigarettes on the table. “If anyone’s going to be observing, it’s you. We’re not observing. If it barks at night, what can we do? My wife won’t be able to sleep; how can she have a healthy child? Your room is right in the middle of the apartment, anything that happens there affects all of us.”

Just then the Bichon Frise ran out, shaking its fluffy tail, its watery eyes peering out of its fur. It looked pathetic. I felt sorry for it. “How about Lou and I switch rooms? I’m on the outside, and even if the dog makes some noise, it won’t disturb your wife, or you. Aunt Men, Lou can give you 200 RMB a month as a cleaning fee, so that you don’t have to worry.”

As soon as she heard there was money to be made, Aunt Men agreed. The majority opinion won. The Duan couple didn’t have anything left to say. I said OK, it’s settled, bent down, and picked up the little dog, handing it to Lou. “What the thing’s name?” Lou spoke stutteringly. “His name is…Ultraman.” Ultraman? I laughed. “Ultraman can only fight with little monsters.” Lou shyly shook his head, like a small child. “I’m a small monster, he always bullies me.” He laughed, and I saw that, when he did, two dimples appeared.

We switched rooms. My room had faced south, and was sunny. Part of me really didn’t want to switch. But for this Ultraman and the little monster, even though I was usually selfish and stingy, I somehow performed this act of great compassion. Of course, I knew that this didn’t mean that I was looking to take anything to the next level with Lou; this was it. We ran into each other in the morning and night, would nod and smile, passing each other by, and that was it.

I didn’t come to this city for him and he didn’t come here for me. We had an amicable relationship; there was no reason to mess with that. He also did unexpected things—on International Women’s Day, showing up with two tickets to Thunderstorm, which was playing at the Beijing People’s Art Theater. I never go to the theater—I get sleepy as soon as the lights go out—but Lou got all choked up watching the performance. As his arms jerked with emotion, I woke up. He watched the play, and I watched him watch it. After it was done, I asked him which character he liked best, to which he responded Fan Yi, but it’s a pity that he didn’t have her courage.

“Why didn’t you find someone new?” Lou asked out of the blue on the subway. Find? Who would I find? I make less than 5,000 RMB a month, I’m over 30, my looks are fading, I’ve no house, no car, no Beijing residence permit; who would I find? I could only ask, “Why don’t you?”

Lou laughed bitterly, moving his head to the side. I looked at the side of his face in the train window. He had prominent cheekbones and flat cheeks, a decent manly countenance. “Well, who would I look for?” Lou had said what I also wanted to say.

Duan’s wife had the baby, a boy, and they held a celebration. The wife was ordered not to work for the next few years, and reserve all her energy for cultivating this single seedling for the Duan family. When the time came, Duan had the traditional one-month birthday party for the child, and got a large amount of cash as gifts.

We all got together on the weekend. Duan’s wife held the baby; it waved its little hands; Ultraman slipped through the crack in the door, ran over to our feet, and licked the baby’s hand. Duan’s wife quickly snatched the baby away. Aunt Men spoke seriously: “Now, Lou, you can’t have this dog here. What if it bites the child?” Lou spoke in a small voice: “Ultraman is shy, plus he’s so small. Even smaller than the baby.” I joined in: “The mom is right here; there’s nothing to be afraid of.”

Duan said nothing. It was an old argument, and not appropriate for the occasion. I made a point of clapping my hands and changing the topic. “Let’s have him pick an object! Let’s see what he wants to do with his life!” Aunt Men was excited, saying yes, yes, let’s have him pick; I’ll put down this gold ring. Duan’s wife was also into it, and ordered Duan to get an official seal, some cash, a colored pen, a ping-pong paddle, chopsticks, a stethoscope, lipstick, a model car, a globe, and a mobile phone. Duan complied. Soon, everything was gathered and spread in a circle on the floor, and Duan’s wife placed the baby in center

Everyone was clapping, Duan’s wife the hardest—maybe she’d had enough of poverty—yelling: “Grab the gold! Grab the cash! Quick, baby! Listen, baby—” Aunt Men joined in, jabbering about grabbing the seal and becoming an official and getting rich—she clearly hasn’t watched the news about corruption in a few years.

I asked Lou which one he wanted the child to pick. “The colored pen,” he said quietly. “I always thought it was a pity I didn’t become an artist.” The baby looked about, darting left and right, then went and solidly grasped the colored pen. Duan’s wife made a real show of disappointment. Aunt Men said it was fine; if he learns to draw, he can have prospects. Duan’s wife spoke acridly—what prospects? Doing art, spending money, starving to death; who’s going to feed him? Someone knocked at the door. “Is Lou Rongbo here?”

A man stood at the door, holding a cardboard box. Short hair, medium height, with very small, narrow eyes, and puffy eyelids. He looked all right though, and had a nice nose. Of all features, a man’s nose is the most important. His was full, and had a nice round tip. He looked educated. Yes, I said, leading him inside.

“Lou.” Only one word, but the room froze, everyone turning their heads curiously. Lou stood there, rigid, a crestfallen expression upon his face, like a pizza that’d just been ruined, sprinkled with sour, sweet, bitter, spicy and salty ingredients all over.

The stranger came in slowly, the box in his arms. Lou still hadn’t moved and, with the box between them, it was as if they were separated by an ocean. The baby just sat on the floor, looking innocently on.

The man managed to force out a sentence: “I’m giving it back; it’s all your stuff.” Lou didn’t reach out, and the guest said something else. Lou suddenly started to cry, silently, just tears streaming down his face. His shoulders began to heave; it was an odd display, not pain, more pure sadness. The guest put down the box, hugging Lou tightly as he cried, so tightly their shoulders touched. I realized what was going on.

Duan’s wife yelled at her husband, exasperated: “Come on, take the kid inside!” The baby smiled, not understanding. He didn’t need to understand. He was a soul that had just come into the world; his past was short and the future was long.

Aunt Men also retreated to her room, with an “Aiya!” I went to the balcony; I need to give them some space, some time of their own. I lit a cigarette, standing at the edge of the balcony; these old-fashioned protruding balconies are pretty rare, and I suddenly wanted to smoke. The air was smoggy; the lights of the building opposite was blurred, and the streetlights above were dim. It was dark everywhere.

I found a pack in my bedside table, Zhongnanhai brand, from a girl in my office who was getting married. I found the lighter, snapped it on, and saw the words on the side of the pack, “Smoking is bad for your health.” I laughed. Fuck that. Isn’t it bad for your health to live inside of smog? I bit down on the cigarette butt, lit it, took a drag.

“He really needs to move out.” Aunt Men sat on the toilet, flipping through an old magazine, face full of frustration. “It’s really not suitable for him to live here.” I was brushing my teeth. Foam leaked out of my mouth as I spoke. “What’s not suitable?” Aunt Men spoke: “You didn’t see, that day? Come on, you understand.” “Understand? Understand what?” I finished brushing, and spat.

Aunt Men rolled up the magazine, and rapped it on the side of the toilet. “To use some new slang, he’s a ji!” I couldn’t help laughing. “Ji? A chicken? Are there ducks, too?” Aunt Men hurriedly explained: “No, ji the character ‘foundation,’ not ji the character ‘chicken egg.’ That ‘ji’ refers to a ‘miss,’ whereas this ‘ji’ means—” I looked at her, through the mirror, and wanted to laugh.

“It means what? A ‘mister’?” Aunt Men saw I wasn’t on the same page, and suddenly got serious. “Miss Hu.” What, Miss Hu? She’d always called me Mingzhu, and now I was Miss Hu. “I’m notifying everyone on behalf of the landlord. I’m not here to solicit opinions. There are elderly and children in this apartment, and a type like Mr. Lou living here really isn’t appropriate.” I took a big sip of water and gargled, spitting it out. “The landlord? When did the Duans become the landlord?” I turned my head.

They went through with it that night, holding a “serious discussion,” blocking Lou in the kitchen and giving a talk along the lines of, “The landlord is taking the place back, we’ve all got to move.” Lou didn’t really push it, just saying that it’s hard to find a place, but that he’d try to move as quickly as possible; as soon as he found a suitable place, he’d be out.

But after a month had passed, Lou still hadn’t found a place. When I had time, I’d go with him to look, but no matter where we went, nothing was especially good. Finding a place these days is harder than finding a partner. Either it’s too far, or the rooms too small, or it didn’t have this or that. I know that in a big city, you can’t be too picky looking for a place to live, but you shouldn’t have to run away just because of others’ unreasonable behavior, either. Lou sat beside me on the bus. It was a rare clear day in Beijing. I crossed legs and I mentioned how Aunt Men had given me a language lesson that day.

Lou was confused, asked me what kind of lesson. I laughed as I spoke: “She said that the ji in basic, isn’t like the ji in chicken.” Lou’s face suddenly turned red. He spoke: “Well, you could say, ji, like basic, means that in a place like Beijing you have your basic freedom, or something…I didn’t imagine that…” I didn’t know what to say next. We got off the bus, and Lou said he was out of food for Ultraman, so we went and bought two bags. By the time we got home, it was dark. We heard a whimpering sound, and gargling: Someone was vomiting.

Aunt Men’s door was closed, and the light was off. Maybe she’d gone to dance in the plaza. The Duans’ door was also shut, and nobody was in the common area, or in my room, or Lou’s room, but we clearly heard vomiting. Lou stood there quietly for a few seconds. “Ultraman!” Where was the dog? “Ultraman!…” Lou cried, frantically searching for the dog.

Finally, he pushed open the kitchen door. Ultraman was there, his mouth blue, his entire body convulsing as he vomited some substance. There were small blue-frosted pills that looked like cold medicine scattered around the floor, some with the frosting licked off, revealing the evil white powder inside. Where did the medicine come from? Such a big package of it? Where did Ultraman dig them out from? I ran through several theories, as Lou picked up the dog and ran outside.

I didn’t follow, but used my camera to document the scene, even though it was really no help. When Aunt Men and the Duan couple came back, they acted like they had no idea what happened, no idea where the pills came from, no idea why Ultraman would eat them, and there was no particular reason why they all left the house at the same time. As far as I knew, these blue pills had been out of production for years, and were only manufactured in small factories in second and third-tier cities. I’d heard Duan’s wife used to work in a pharmaceutical factory.

I don’t want to conjecture; there was no proof. My only evidence was those blue pills, and what use was that? Ultraman was only a dog, he couldn’t talk, couldn’t testify. In the end, he didn’t die, but the vet said he may never bark again. He was an innocent sacrifice, unlucky to have an owner who was disliked.

“I’m off.” A week later, Lou came to bid me farewell. His hands were in his pockets, shoulders hunched, a deliberately relaxed appearance that couldn’t hide his melancholy. I made the phone shape with my fingers and put them to my ear. “Keep in touch.” Lou laughed. “Of course; the new Spider-Man is about to come out, we should watch it together.”

The edges of my eyes felt hot, and I lowered my head; I didn’t want him to see. “Of course, we gotta watch Spider-Man. I like Spider-Man.” I love Spider-Man. He’s a hero, but most of the time he’s just an ordinary person, hidden in the crowd. Now that Lou is gone, I think I will move out soon.

Author’s Note: This story is about Beipiao (北漂, “Beijing Drifters”) and roommates who live together but are not romantically involved—it’s a brand new relationship among many migrants in big cities. People in the story are rejected because they are different. Spider-Man stands for every common individual: they may be ordinary, but when facing adversity in life, everyday people are capable of showing their heroic side.

Yi Bei 伊北

Yi Bei hopes to bring a female point of view to his stories about relationships and urban life: the pressure for single women to find partners, for young wives to balance work and family, and for female migrants to find success in a materialistic and competitive society. Born in 1983 in Huainan, Anhui province, Yi got his master’s degree in literature from Beijing Normal University, and has published 13 works, including novels, essay collections, and biographies of well-known female writers from the Republic of China era, such as Eileen Chang.

I Love Spider-Man | Fiction is a story from our issue, “Modern Family.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.