Rocketing divorce rates have alarmed the government—is a culture of infidelity to blame?

Lily (pseudonym) did not think twice about when a family friend’s colleague offered to drive her home after dinner. He was sober, her place was on the way, and, besides, her friend was a powerful guy. No one would want to upset him.

Their conversation was innocent enough, as they discussed how his 10-year-old son should study to attend a top university like her. But when they arrived, he leaned over to forcibly kiss her. For weeks afterwards, he continuously texted her, asking her out to dinners, clubs, and KTVs before finally taking the hint to stop.

There’s nothing unusual about a story like Lily’s. The private lives of many married men are filled with mistresses, mystery girlfriends, and KTV visits, if rumors and reports are believed. Renmin University’s Professor Pan Suiming, a specialist on Chinese sex lives, has estimated that 34.8 percent of men had engaged in sexual relations outside of marriage—a conservative figure. An online poll by Tencent had the number even higher, at 60 percent (and that’s just those who admit it).

The issue is prevalent enough to have spawned a minor industry, devoted to providing solutions to the problem of having an unwanted “little third” (小三) in your life, as mistresses are often called. Teams of expensive experts—known as “mistress dispellers”—claim to offer wives tips and makeover advice to reclaim their wandering spouses, while promising to ward off mistresses with a range of dubious tactics like bribery and threats.

Anthropologist John Osburg is not surprised by these studies. During research for his 2013 book, Anxious Wealth: Money and Morality Among China’s New Rich, the associate professor of anthropology at the University of Rochester befriended and interviewed numerous wealthy businessmen in southwest Sichuan province. “The infidelity rate of my research subjects was nearly 100 percent,” he told TWOC. “Of course, my sample size was relatively small and the subjects had a lot of similarities.”

In a 2009 Guangzhou case, a street fight ensued after a woman caught her husband on the bus with his mistress (VCG)

Although infidelity is nothing new in society, the issue has gained public attention in recent years in part due to China’s skyrocketing divorce rate, which has doubled in the last decade, with many citing extramarital affairs as the cause. In 2017, a representative of the Beijing No. 2 Intermediate People’s Court told the South China Morning Post that 93 percent of divorces stemmed from either affairs or domestic violence.

In an attempt to clamp down on divorce and promote “traditional family values,” the government is introducing a “cooling off” for couples seeking separation, during which they are encouraged to reconcile their differences through counseling. Parental pressure may also have helped preserve unhappy marriages in the past—but, according to Beijing marriage counselor Li Kening, who has worked for over nine years in the suburban Tongzhou district, the situation is quite different today.

“Some young couples are actually being pressured to divorce by their parents,” Li told TWOC. “If a woman’s parents hear that her husband has had an affair, or is not treating her right, they may tell her to seek a divorce. Likewise, mothers of 妈宝男 (mommy’s boys) find constant fault with their daughters-in-law—even divorceable faults.”

Beijinger Mr. Zheng agrees. Believing that city life makes people more liberal, he isn’t pushing his 31-year-old son into marriage, preferring him to find a woman with whom he has emotional and physical chemistry. However, “If my son fell in love with another woman and wanted to leave his wife, I would advise him to work harder to make his first marriage work; if I couldn’t persuade him, I would support his decision to divorce,” Zheng said. “I am Chinese, and it is still important to keep the family tradition.”

While the one-child policy has undoubtedly elevated the importance of their child’s personal fulfillment and happiness in parents’ minds, Osburg’s research provides other insights. One major reason that Osburg’s research subjects did not pursue divorce was peer—rather than family—pressure. He cited the case of a businessman who fell in love with a nightclub dancer, but ultimately decided to stay with his wife, out of concern for how his business associates and peers would view such a partner, or judge his character and sense of familial responsibility.

On the other hand, Osburg noted, his subjects seemed to be happier—and more “in love”—with their mistresses than their wives. The 1950 Marriage Law, which abolished arranged marriages, was not quite the societal game-changer it first appeared. Class differences were a perennial obstacle, tradition another: Parents still had a great deal of say in their children’s affairs, matchmaking remained prevalent behind the scenes, and there was virtually no dating culture. Marriages and divorces even needed approval by each partner’s work unit.

The TV series Dwelling Narrowness started debate on its main character’s decision to become the mistress of a government official (VCG)

Influenced by new models of romance and partnership in Hollywood movies and Cantopop in the reform era, young people wanted to marry for love, although many did not know how. Osburg says his subjects often talked about fatherhood, and their pride in their children, but rarely their satisfaction with marriage. Instead, they lamented their lack of experience, or their innocence at the time of their marriages. “I went out with [a woman] and everybody started talking about us getting married, so we did” was a typical refrain.

And while reform brought back romance, it also marked out new inequalities. While ancient concubine culture usually came alongside a moral justification—getting male heirs to continue the family line—in addition to status-signaling for elite men, Osburg states that the wealth gap has exacerbated gender inequality, creating a ready supply of young women willing to become mistresses for material gain. His subjects lament that some women now throw themselves at wealthy men, hoping that an affair would provide them with financial support—or, as the saying goes, “A man goes bad when he gets rich, a woman goes bad to get rich.”

As for men, mistresses can be a status symbol, especially as the gender disparity caused by the one-child policy has made women a rarer “commodity.” Tencent’s survey suggests that men with higher incomes are more likely to cheat, and that IT, finance, and education are the most adulterous professions. Osburg observes that many of his subjects work long hours outside of the home, and some worry about being considered prudish if they do not join business partners and colleagues in bonding activities involving alcohol and prostitutes. Then, there are those who rationalize infidelity as that’s just how men are.

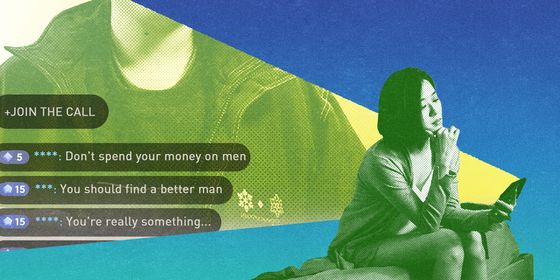

However, Li notes that adultery is now no longer the preserve of the wealthy. “It used to be that to keep a mistress, you needed to be rich,” he tells TWOC.“With the rising use of social media, we are starting to see lots of people pursuing one-night stands, many of which can bloom into full-on affairs.”

As divorce becomes less taboo, dating culture more prevalent, and parents less able to exert control over their children’s love lives, both sexes are finding more opportunities to pursue their ideal life partner—which may, in the end, have a positive influence on reducing infidelity. There’s even hope for the current “divorce generation,” Li suggests: “People can learn from their failed marriages and better prepare for their next one.”

Additional reporting by Tan Yunfei (谭云飞)

State of Affairs is a story from our issue, “The Masculinity Issue.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.