Jin Xu's new book puts silver at the center of dynastic fortunes throughout Chinese history

In 1916, as the silver yuan collapsed and inflation skyrocketed, author Lu Xun wrote that the worthlessness of Chinese paper notes forced him to "ignore patriotism, and ask for notes issued by foreign banks." Or worse still, turn to the “weighty comfort and delight” of a heavy bag of silver: “How easily we become slaves.”

According to Jin Xu (Chief Financial Commentator at the Financial Times Chinese) in Empire of Silver, silver was as addictive as opium for imperial China, and just as corrosive. Xu's book, originally released in Chinese in 2017 and now translated by Stacy Mosher, attempts to explain the "Great Divergence," one of the oldest debates in Chinese history: How did China, with its millennia of grandeur and sophistication, get bettered by a tiny group of barbarian statelets huddled on the western-most tip of the Eurasian landmass?

According to Xu, one transcending thread has been neglected—monetary policy. Xu’s emphasis on systems makes for a dense academic study, utilizing Tolstoy's view of history for a monumental take on China's long past, with emperors and their sharpest ministers left powerless against calcified financial systems.

Over China’s long history, financial value was endowed within a staggering variety of materials and objects. The cowry shells of ancient dynasties like the Shang (1600 – 1046 BCE), the Tang’s (618 – 907) bolts of silk cloth, the Song dynasty’s (960 – 1279) fibrous jiaozi (交子) notes printed on mulberry bark, or the Qing’s (1616 – 1911) boat-shaped yuanbao (元宝) ingots and hefty strings of copper cash.

But for Xu, silver was the most influential of them all. In her analysis, China’s 19th and 20th century catastrophes were set in motion the moment silver entered mass circulation, as the rest of the world came to value gold more highly. “Is it not ludicrous,” wondered Qing reformer Kang Youwei, “That an ancient nation with 5,000 years of civilization and 400 million people could perish merely because of silver declining and gold rising?”

Xu takes us back to the Song dynasty to make her case. Back then, she argues, commerce was inferior to politics. Merchants were on the bottom rung of society, and money was an instrument of state power rather than mercantile profit. While we are familiar with paper money as a symbol of the modern world, Xu suggests that at that time China actually suffered because it relied on such “fiat currency"—money which had value because the government said so—rather than using coins made of precious metals as the Europeans did.

Without the restraint provided by an independent central bank (like the Bank of England in the 18th century), the state just printed more money to meet the steep costs of war with the Jurchen and the Mongols, leading to rapid inflation. By the Yuan dynasty (1206 – 1368), playwright Guan Hanqing’s drama Injustice to Dou E (《窦娥冤》) had tricksy characters gifting paper money as tokens of thanks, when everyone knew both the notes and the gesture had absolutely no value.

Silver provided respite from runaway inflation, explains Xu. People were so desperate for cold hard cash during the Jin dynasty (1115 – 1234) that they resorted to robbing graves in search of it. One Ming dynasty (1368 – 1644) author in the anthology Wu Za Zhu ( 《五杂俎》 ) sang praises of these new silver coins compared to flimsy paper: “Water or fire could not destroy them, rats and insects could not invade them, and they could be passed around 10,000 times and retain their original quality.” Despite the Yuan and Ming (keen to retain their power over currency) issuing edicts forbidding silver's use, they were eventually swept away by market demand, legalizing it for circulation in 1567.

Broad in scope and bold in execution, Empire of Silver charts the ebb and flow of the silver tide over the following dynasties, a current almost entirely dependent on sources in Japan and Latin America. Although it caused a boom in the Ming and Qing, it led to hoarding and increased tax burdens when the supply was low, sparking public anger and revolt. Xu even suggests silver explains the corruption of ministers, whose pay lost value as inflation rose forcing them to look elsewhere to support their lifestyles.

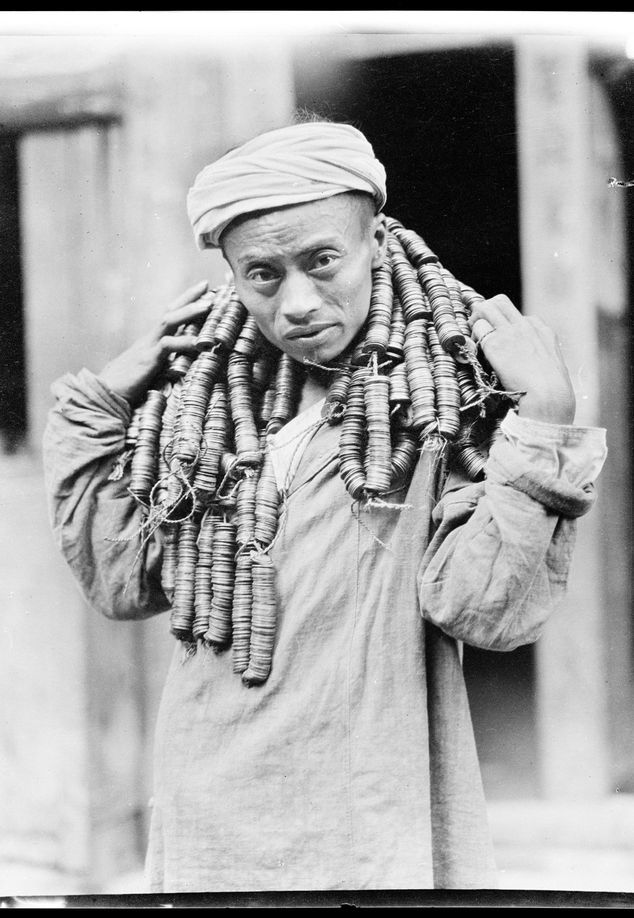

Xu's argument and narrative form a neat circle when she comes to describing how the Republican government, like the Song before them, began to issue paper money and banned silver in 1935. Lu Xun noted how peasants marveled at how convenient bank notes were to carry, no longer walking to market with reams of copper cash strung over their shoulders (see below).

But Xu giving silver the spotlight detracts from the factor which seems to have been the root cause of imperial downfall: money was wielded for political expediency rather than commercial profit. This was the reason the Republicans ended up repeating the same mistakes in the 1930s as the Song had done centuries before—the reserve Central Bank was “merely a counting-room cashier controlled by the government.”

The outcome was predictable: endless warfare meant printing more paper notes, starting the worst case of hyper-inflation in modern Chinese history. Xu argues this was the Nationalist government’s death-knell, ensuring it “galloped down the road of inflation to extinction.”

Chiang Kai-shek blamed China’s new banks for the chaos, calling it “an even greater sabotage of the revolution than the carving up of the country by warlords.” For him, bankers were to “absolutely obey the orders of the central government,” in the same manner as merchants had the imperial treasury.

Empire of Silver paints a tragic story of systemic failure, monetary cycles playing out in tandem with the dynastic ones, and characters blinded by their obsession with political expansion over anything else. Xu masterfully untangles the complex threads of China’s financial slow-motion collapse, offering a convincing narrative of how the asset-rich Middle Kingdom lost the race through their finances and the materials they made them from. As silver comes after gold, so China fell behind the West.

Cover Image: Silver "Yuanbao" ingots from the Yuan dynasty, from VCG