Keeping cool with no electricity was no easy feat in ancient China

There is nothing worse than being sweaty and flustered on a scorching summer day, but at least we’re able to escape into beautifully air conditioned buildings these days. Before electric fans and air conditioning units, people in China weren’t so lucky—and the heat could be fatal.

Imperial records show that 11,400 people perished in Beijing in the summer of 1743, as temperatures soared to over 44 degrees Celsius for dozens of days on end. While during the Tang dynasty (618 – 907), the poet Wang Wei (王维) wrote Harsh Summer (《苦热行》) to complain about the sultry season: “Grass and trees are scorched; rivers and lakes are dry.”

Given the hazards of hot temperature, ancient Chinese thought it was best to rest during the hottest days. One old saying stated: “A true man never makes money in the scorching sixth lunar month.” Even criminals sentenced to death were reprieved until after the summer months until “autumn executions (秋决)” began. Staying cool was clearly a serious matter in ancient China, but luckily they had some ingenious ways to avoid the worst of the heat.

Dressing for the weather

Bikinis were out of the question back then, but thin, translucent materials helped folk stay cool. A painting from the sixth century named Proofreading in the Northern Qi Dynasty (《北齐校书图》) by artist Yang Zihua (杨子华) shows scribes wearing loose-fitting robes with slip dresses underneath as they worked.

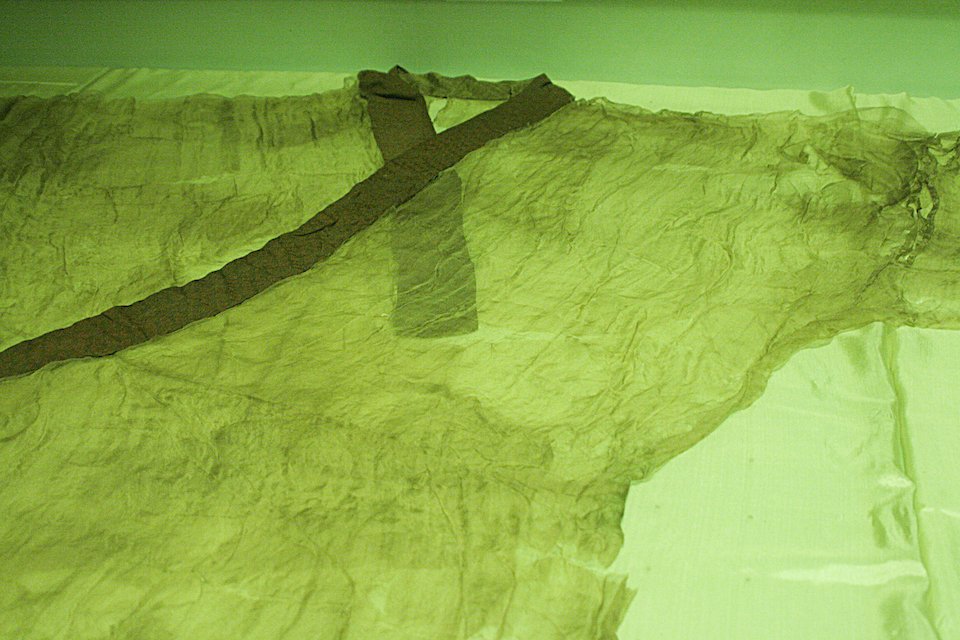

In 1972, archeologists unearthed a silk robe weighing just 95 grams from the Western Han dynasty (206 BCE – 25 CE) in the Mawangdui Han Tombs in Changsha, Hunan province. The thin yet durable dress was known as susha danyi (素纱襌衣), or “plain silk single robe.” The garment was named for its plain color and the fact it could be worn as a single layer with no other clothing.

However, the silk robes of scholars and officials were not affordable to most common folk. Instead, they might wear zhuyi (竹衣, “bamboo clothes”), which helped the wearer avoid sweating and didn’t stick to their skin. In addition, women sometimes wore jingyi (胫衣), which were long pants with an open crotch. Wearers would also don a long skirt known as a chang (裳) to cover up their genitals.

Imperial ice desserts

Like many today, Chinese of centuries past enjoyed ice cream and iced beverages to keep cool in the stifling heat of summer. But back in Zhou dynasty (1046 – 256 BCE), ice was a luxury held exclusively by the imperial court. According to the Confucian classic Rites of Zhou (《周礼》), the Zhou court established a specialized government department called the bingzheng (冰政, “ice administration”) where 80 employees known as lingren (凌人 “ice men”) took charge of the government’s ice store.

Every December, the ice administration would organize the collection of ice blocks from rivers before storing it in an underground “ice warehouse,” or lingyin (凌阴), insulated from the heat above ground. Only the most prestigious and senior officials were afforded the luxury of ice, and the emperor would gift ice cubes from his stores to those considered worthy. This was considered a huge honor for recipients, who would use the ice to cool their homes and to preserve or chill food. The practice lasted until the late Tang when officials discovered that saltpeter (which was being extracted from quarries in large quantities to make gunpowder) could be used to rapidly cool water and form ice. Since then, man-made ice became possible even in the summer

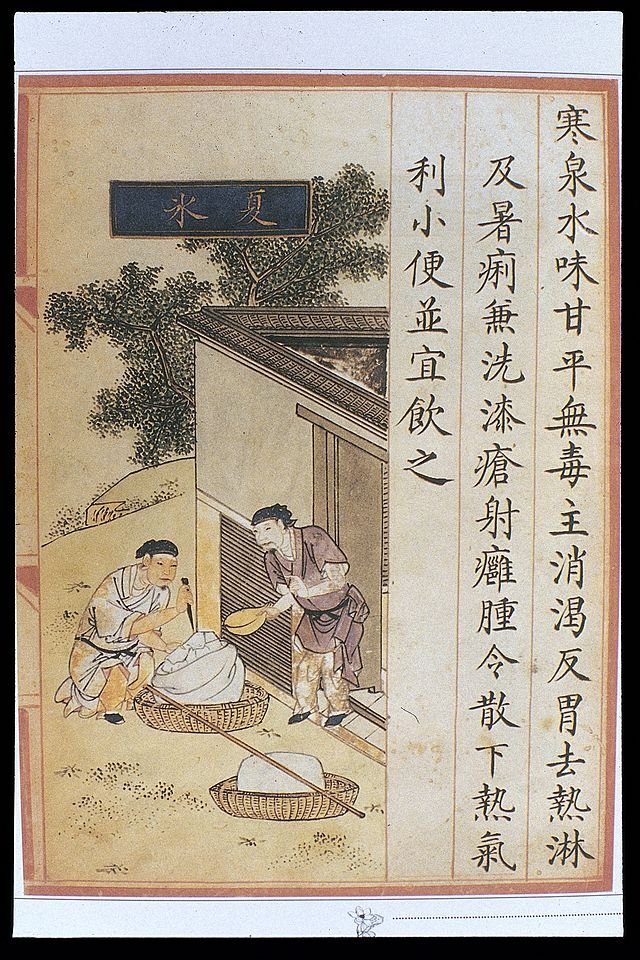

Also in the Tang dynasty, sushan (酥山), a frozen dairy product introduced from nomadic tribes to China's north, became highly popular. Sushan was a chilly drink made by mixing boiled buffalo milk with sugar or honey, then pouring the mixture into a container shaped like a mountain peak and storing it in the lingyin to freeze. In the Song dynasty (960 – 1279), chilled drinks made of fresh fruits sprung up across the country. One of the most popular, “lychee cream water (荔枝膏水)”, is still common today. It is made of lychees and plums mixed with cinnamon and cloves for a refreshing taste.

Cool architecture

Keeping cool sometimes required careful architectural planning. In ancient times, living quarters were often built around artificial lakes and reservoirs, and flowers and plants were added to increase the moisture in the air and provide shade.

During the Southern Song dynasty (1127 – 1279), the emperor often spent summers in his “green cold palace (翠寒堂)” where bamboo, lotus flowers and other plants were cultivated, and a large man-made waterfall ran to reduce the heat. Dozens of gold basins were filled with ice from the imperial ice store, and placed in the palace and the emperor's bedroom. The structure was so effective that Hong Mai (洪迈), a scholar, apparently felt so cold in the imperial palace in summer that Emperor Xiaozong had servants fetch him a coat, according to Song records.

There were even stranger ways to keep cool. According to the Miscellany from Youyang (《酉阳杂俎》), a collection of literary sketches from the Tang dynasty, Emperor Xuanzong once chilled two live snakes and had them sent to his overweight cousin King Shen, who couldn’t stand the heat in summer. King Shen wore the snakes around his waist as a cooling belt.

Even after all this, some still struggled in the heat, and instead took the attitude of the famous calligrapher Wang Xizhi (王羲之) who wrote in a work called “Today Is So Hot (《今日热甚帖》)”: “It’s so hot today, so why don’t we all just mind our own business? I am so exhausted, that any visitors to me will be rejected.”