From shelter hospitals to construction sites, hear from three ordinary people in quarantine in China’s biggest city

On April 13, 18 days after Shanghai began locking down neighborhoods in response to what has become China’s worst outbreak of Covid-19 to date, a number of communities let their residents outside the compound gates for the first time for reasons other than nucleic acid testing after reporting no new infections for over 14 days—though many were quickly ushered back in after this temporary reprieve as reports of new cases continued to mount in the ten-thousands across the city.

Over the past month, residents of China’s biggest city have shared experiences tragic, shocking, as well as hopeful as they battled food shortages and tried to get their voices heard. TWOC spoke to four migrant workers in Shanghai on how they are surviving lockdown when unable to work or isolate in safe conditions. As part of our collaboration with renowned podcast Story FM, we hear from three more Shanghai residents under quarantine in wildly different locations—on a construction site, in a hotel, and at a temporary “shelter hospital”—and how they got the assistance they needed.

My name is Xiaoyu. I am a university freshman.

My auntie is 50 years old, and she has been working in Shanghai for more than 30 years. She and her husband are both migrant workers from the countryside. My aunt’s husband is a low-level foreman in the construction industry, and she does cleaning jobs and other part-time work.

-1-

Lockdown on the construction site

2022 was an important year for my extended family. My aunt’s daughter got married during the Lunar New Year.

She’s my aunt’s only daughter, so Auntie was ecstatic to see her settled down. On February 20, I accompanied Auntie to Shanghai from our hometown in Anhui province. She was preparing to make a fresh start in the new year.

At the start of March, there were some signs that Shanghai was considering measures against the increasingly severe outbreak. My parents’ company closed down, and all the employees were required to stay at the office. That night, we had a video call with Auntie, who said all was well on the site.

However, the following evening, their construction site was shut down. Reportedly, someone there was a close contact of a Covid-19 patient.

Employees at my parents’ company could continue working as long as they had access to a computer. But once a construction site shuts down, the workers have nothing to do. And if they couldn’t work, they earned nothing, because they were paid by the hour.

What’s more, the middle-aged men you see on most construction sites are usually the backbone of a whole family. If the work dries up, an entire family loses its income. That’s the worst part.

-2-

Sudden quarantine order

On the ninth day after Auntie’s construction site shut down, the pandemic blew up in Shanghai. On the night of March 29, Auntie and around 20 other workers were told to go into centralized quarantine.

Since the construction site was already locked down, “centralized quarantine” simply meant they were asked to immediately vacate their dormitory and be taken to an unfinished building on the construction site itself. None of them disobeyed the order.

Imagine what it’s like: an empty room with no water, no electricity. There was dust all over the floor that hadn’t been cleaned up after the renovation. Auntie said the smell made her want to throw up as soon as she entered the building.

She doesn’t remember how she slept that night. There wasn’t time to grab any personal items, like a quilt, before leaving, so Auntie slept under a thin piece of cloth. She said that when she woke up the following morning, her mouth and nostrils were full of sand.

There was no breakfast that morning. At 1 p.m., there was a delivery of instant noodles. “How are we supposed to eat this without electricity or water?” the workers asked. But the noodle packets had been tossed at them over the wall. There was nobody to listen to their complaints.

When they couldn’t fight their thirst anymore, some workers began drinking water from a fire hydrant nearby. Auntie was reluctant at first, seeing how dirty the water was, but in the end she gave in.

They ate instant noodles for about three to four days. When Auntie called us, we asked, “Have you eaten? Is there still no food to eat?” She replied there were just two packets of instant noodles per day and nothing else.

She spoke as if this were perfectly natural, but I was shocked. It’s the 21st century, and it was in Shanghai. Wasn’t Shanghai a world-class city?

It was cold in Shanghai during those days. Auntie caught a cold, and she wasn’t the only one. But there was no medicine and no one to check up on them. The workers were unhappy but were afraid to say anything. They’d called up their supervisor, but their supervisor replied, “I’m also in quarantine. I can’t do anything.” No matter how many times they called, nobody would take responsibility.

Construction sites are contracted out to many different companies. Unlike a company or a school, there’s no centralized management. Instead, they’re a collection of different parties drawn together by profit, and when there’s trouble, they dissipate as quickly as they come. People like my aunt and her husband were ordinary farmers, honest people who would always say, “Let’s just hang in there a while longer, and it’ll pass.” Until it didn’t.

The next time I called Auntie, she had such a high fever and a sore throat that she could no longer talk. I told her, point-blank, “I’m going to call for help on the internet. You can’t go on like this.” She still kept telling me she didn’t want to make a fuss. I asked her, “Auntie, is keeping your head down more important than your life?”

-3-

A cry for help

I posted a cry for help on Weibo. I didn’t write a draft, just typed:

“Please help the construction workers at the X Group. They have no water or electricity. They can only eat instant noodles when they’re hungry, and drink from the fire hydrant when thirsty.”

I wrote this at 1 p.m. By evening, the post had been read over 200,000 times and shared several thousand times.

I was touched by one young woman who was also stuck at home, who told me she had an extra quilt she could give my aunt. She called a taxi, and told the driver to take it to the entrance of the construction site for my aunt’s husband to pick up.

On the afternoon of April 2, Auntie said they finally had a meal delivery. It was cold, but it was better than nothing.

I think I was possessed during those few days. I refreshed my Weibo page every moment of every day to see if any more people had shared my post. By April 3, there were over 2 million views.

Yet by the 4th, there was no improvement to their condition. I was furious. I went into my WeChat groups, my WeChat moments, my QQ groups, and Bilibili. No matter what, I asked my friends and followers, help me spread the word.

I also called the subdistrict office, but the line was always busy. Later, someone on the internet told me that everyone at the subdistrict office had been put under quarantine and couldn’t help with anything.

-4-

A reply

By the evening of April 4, my story was trending online within Shanghai. There were almost 6 million views. We finally got a call from the Shanghai Center for Disease Control. They sent me a text message saying, “We are looking into your matter. Please wait for further updates by text message.”

Later, a manager at the construction site called me, saying. “We have learned about your aunt’s situation and the company has called an emergency meeting about how to manage these workers.” The next morning, a higher-level manager called me saying, “We are aware of your situation. Please stay put, and we’ll deliver supplies by this afternoon. Our company has made some errors in this matter…” They then proceeded to apologize. I think that if the authorities hadn’t put pressure on them, they wouldn’t have done this.

I didn’t do much. I just sent out a distress call. I wanted more people to know my aunt’s situation. But how can the others like my auntie, living on the margins of this big city, get their voices heard?

After my aunt got the help she needed, I posted another message on Weibo: “Thanks to everyone for your help. Please turn your attention to those who are in even more need than we are—those who have no ability or money to seek medical attention. Please help them.”

I hope we can pay more attention to the weaker members of society. Our society isn’t tolerant enough of people of my parents’ generation. They fall farther and farther behind the times. They will never come up to you to tell you directly, “I need this” or “I don’t need them.” They just accept everything as it’s given.

In my parents’ office, which is still locked down, there is a cleaning woman. Today, my parents got her some fresh vegetables, but she insisted she didn’t need it.

In the end, I had to physically shove it into her hands. Only then did she say, “All right, thank you.” The moment she held the vegetables, tears began gushing down her face.

Story FM: Xiaoyu’s auntie and the other construction workers have gotten help. But we don’t know how many other people like them are unable or afraid to ask for assistance.

With millions of people needing help, it’s inevitable some people will fall through the cracks. Today’s second speaker, Luo Su, contracted Covid-19 in mid-March.

In our imagination, as soon as you get diagnosed, someone will follow up with you to check where you’ve been, and come to take you to the hospital and disinfect your home at the earliest opportunity. But Luo Su experienced none of this. She wasn’t even one of the 25 million residents sampled during Shanghai’s citywide tests in early April.

This is her story.

My name is Luo Su. I was born and raised in Shanghai, and I’m one of the people who contracted Covid-19 in the current outbreak. After self-medicating, I am now testing negative, but still under quarantine.

-1-

Catching Covid at the gym

The week of March 11, there was no inkling of what was to come. We’d always thought we were safe in Shanghai.

I work in the biomedical industry, so I’ve been inoculated with a vaccine that’s still undergoing clinical trials. After I’ve been vaccinated, I’m supposed to go for an antibodies check. My antibodies count was 228, well above the minimum threshold of 40. I thought I was quite safe as well.

I had surgery last December and put on a lot of weight during my recovery. Afterward, I really wanted to exercise, so I frequently took group classes at the gym. At that gym, all customers were supposed to get their health codes checked at the door, but in reality, they were quite lax.

On March 18, I went to a spin class. After that, the temperature in Shanghai took a nosedive, and I began to feel chills. I took a nucleic acid test at around that time, and my result was negative, but by the 24th my nose was quite congested and my throat was dry.

I joked to my parents, “Maybe I got Covid!” They said, “Don’t be ridiculous. That disease is not that easy to get.” I decided to self-monitor for a while longer. Back then, if you’d gone to your community and told them you think you caught Covid, they’d also think you were crazy. After I returned home on the 24th, I decided not to leave again.

The next afternoon, I got a call from the gym: “Someone from your class on the 18th has been diagnosed with Covid-19.”

I started panicking as soon as I hung up. Suddenly, I realized I no longer had a sense of smell. My parents tried to comfort me, “That’s just because you’ve had a cold for a few days.” But I suspect they weren’t totally sure either, so I told them, “Stay away from my room from now on.”

-2-

The whole family’s infected

I had trouble falling asleep that night, because next day, the community was sending us self-testing kits. I had a bad feeling, so in order not to infect other people, I decided to stay home and wait for the self-test rather than go to the hospital.

My father had planned to go with some relatives to sweep our family tombs on the 27th. Though he hadn’t had any symptoms, he decided to drive to the hospital to take a test.

The results came out a few hours later—positive. Immediately after that, our whole family of three was diagnosed with Covid-19.

The first thing we did after getting diagnosed was to call the pet shop to take our dog away. When they came, we all clung to him and cried, as if he was leaving forever.

I’m sure my dog thought we were acting strangely. “What are you doing?” he seemed to be asking us. There was a special backpack we used every time we took him out to play or to the grooming shop, so in his mind, that backpack meant we were taking him on an adventure. On that day, too, he dashed into the backpack as soon as we opened it. But when we handed the backpack over a pet shop owner, he began to bark. He could smell us getting farther and farther away from him.

We made preparations to leave our home. It felt like someone could arrive at any moment to take us away. My parents filled two cases with our personal items, but nobody had come for us by 10 in the evening, so we took our pajamas out of the suitcase and slept.

The day after we got diagnosed, we received some phone calls asking where we’d been in the last four days, but they didn’t give us any advice for how to treat our condition. I called up a doctor I knew, and bought some medicine they suggested.

By the fourth day, we were still at home. But my symptoms began to improve. I began to regain my sense of smell. When I opened my fridge, I could smell everything in it.

I used the self-testing kit and got a negative result, and immediately told the news to my community and the local CDC.

Yet during those couple of day, my mother began to lose her sense of smell. I knew then that I had infected her, because her symptoms were two days delayed compared with mine. At the time, I heard that they were running out of beds in shelter hospitals. By my reckoning, if nobody came to take us away, we would quarantine at home and recover on our own. The omicron variant is highly infectious and hard to detect, but it isn’t as virulent as other types of the virus. At that time, we weren’t too worried.

-3-

My parents leaving

If anybody could have beat this thing on their own, it was my mother. She’s a tough woman. Back when she worked in a state-owned factory, she’d been awarded the country’s highest honor for a female worker. Yet in my family, the disease affected her the worst.

In just four days, my mother lost 5 kilograms. Omicron can reduce your appetite, but besides that, she was constantly stressed out by reports of horrible conditions in the shelter hospitals. She wouldn’t show her worries to anyone else, so it ate away at her from the inside, making her thinner and thinner.

On the evening of the 29th, a doctor called to tell my parents to prepare to move to the Shanghai Geriatric Medical Center.

I didn’t know how conditions were at the Geriatric Center, and I was worried because my father had two heart attacks in the past. I asked the doctor whether they could make an exception. “Who asked you to get sick?” he snapped, and hung up.

I felt really guilty then, because I was the one who’d infected my parents. I cried and apologized to them. My dad said, “What’s there to apologize for? We’re family. We’ve lived through tougher times before. I’m sure someone will take care of us once we arrive at the hospital.” The minibus came for them at 10:15. The whole bus was full of elderly people, and I stood at my window and cried as I watched them drive away.

Then I got a call. “You will be sent to a shelter hospital,” said the person on the other end. I told them my test results had already returned to negative. “We’re only doing what we’ve been told,” they replied. At 11 at night, the community made me take another test, and the result came back positive the next day. When they took me away, I didn’t know where I was going and for how long.

By the time they dropped me off at my quarantine hotel, I’d hit rock bottom. They provided you with three meals per day, but I didn’t go pick up my dinner that night. At 8, when I called my mother, I said, “Mom, I don’t know when they’ll let me out. I don’t want to eat anymore.”

My mother is not a demonstrative person. That was the first time she’d ever shown emotion in front of me. She said, “You have to eat. Take care of yourself.” We were both crying when we hung up.

-4-

A Waiting Game

I didn’t find out until later that there was no doctor at the quarantine site. How long will I be here? What kind of treatment will I get? Where will they take me afterward? I had no answers. I could only wait and try to manage my own emotions. My parents were being taken care of, and my dog was being cared for at the pet shop, so I told myself I had nothing to worry about.

By the third day, my feelings had calmed down. To cheer me up, my friend told me, “Look at you, you have a bed to sleep in, a shower, and they feed you three times a day so you don’t have to queue up to order vegetables online. What’s there to complain about?”

I also feel kind of guilty. My living conditions are several magnitudes better than what I’ve seen online. All of Shanghai is running out of resources, and there are constant reports of medical workers getting infected. There are others, including elderly people, who need these resources more than I do.

On April 4, Shanghai conducted a citywide nucleic acid test. I felt hopeful, because one of the conditions for me to return home was two negative tests. But when I called them up in the morning, my quarantine site told me we weren’t included in the test. It was as if someone poured cold water over me.

I joked to my friend, “Maybe I’m no longer a Shanghai resident now that I’ve tested positive!”

I kept on testing myself. By my ninth day in quarantine, I’d gotten 16 negative results, and they finally did a centralized test for people in this quarantine center. It took three more negative results before they told me I was free to go.

Looking back, I believe everyone I called gave me all the information they had. I think it’s all a matter of personality. Some people will only give you what they know for certain. Others will go to any length to help you, will give you any sliver of information they can find.

I don’t blame any of them, because we’re all in this together. I’ve also panicked, been in despair; and they handle far more cases than I do every day.

But now the question is, what’s next for Shanghai? When will be allowed to go buy groceries as normal? When will be allowed to work? Once I return home, will it still be the home I left?

Story FM: On April 14, Luo Su returned home. She told us the most important thing for her to do now is to figure out how to retrieve her dog from the pet shop. Only then, will she truly feel like she’s come home.

Yet experiences like Luo’s are in the minority. Not all pet-owners can send their pets to safety, like she did. Our next speaker, Cara, tells us what happens when you can’t.

-1-

“It's not so awful as long as I have my cat”

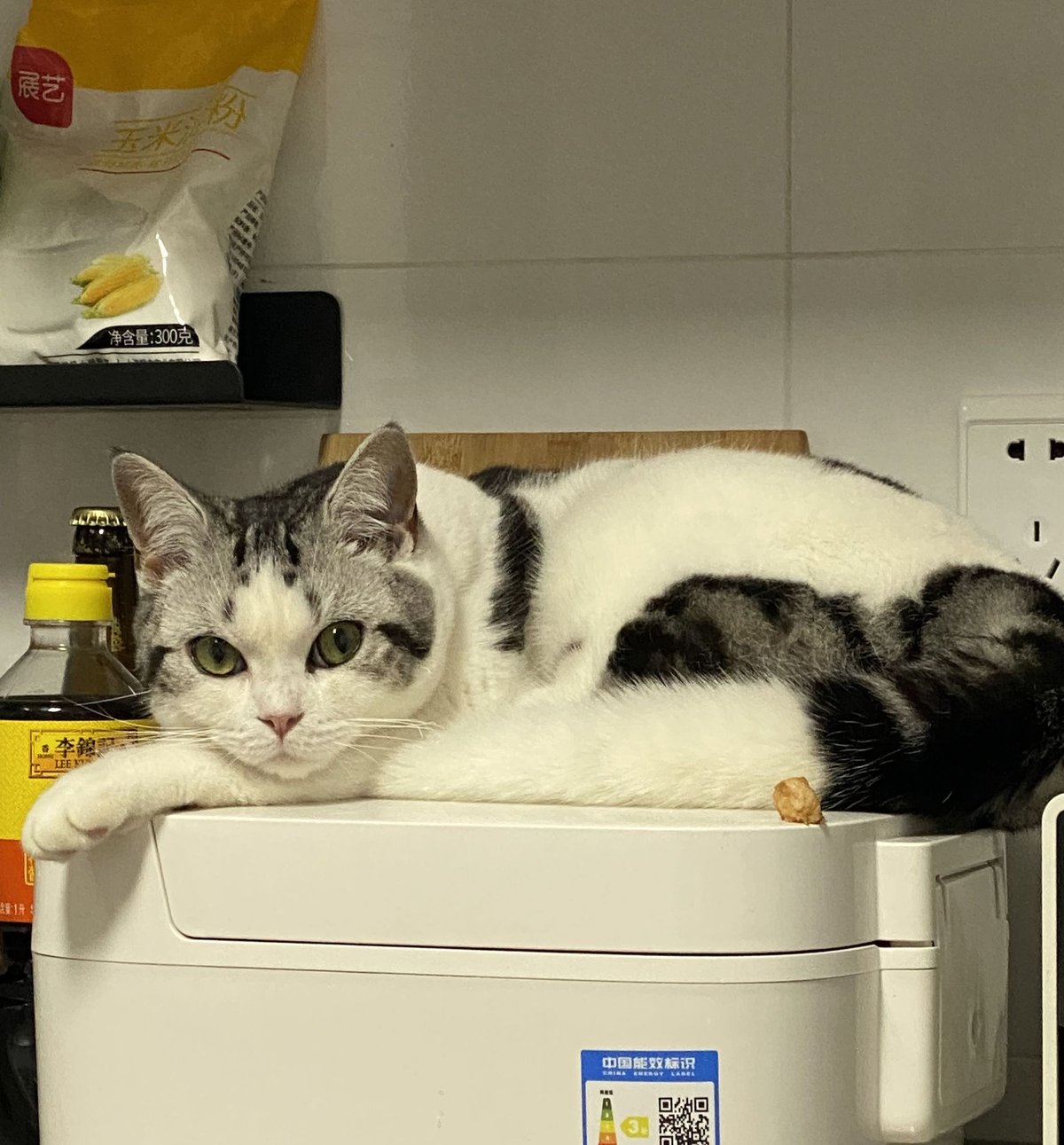

I have an American Shorthair kitten called Jiumi (酒米 jiǔmǐ), after a delicacy called jiumifan (酒米饭, “wine rice”) in my home province, Sichuan. It’s also pronounced similarly to 啾咪 (jīumī) a slang term for “I love you.”

She has a black and white coat with a big white patch on her back, as if she ran out of ink in the womb. She’s very sweet. Every night when I get home, she’s always waiting for me on the sofa. This one time, I went back to my hometown for a wedding and stayed overnight. On the home surveillance system, I saw her waiting on the sofa from 7 to 10 in the evening. That went straight to my heart. I thought, “The world isn’t such an awful place, as long as I have my cat. She’ll never abandon me.”

My company began asking us to work from home on March 10. At the time, I wasn’t too worried. I didn’t think I’d catch the virus, and if I did, I’d send my cat to stay with a friend in my apartment complex.

-2-

Diagnosis

I developed a sudden a fever on April 1, and got notified that my nucleic acid test showed abnormalities. They began testing me individually, and diagnosed me on the 5th.

I wasn’t able to send my cat to my friend’s apartment as planned. The CDC told me that if my community agreed, I could quarantine at home. For Jiumi’s sake, I asked my community for permission to do this, but they refused.

At that point, I began to panic. I kept calling them to explain I had a pet. They insisted, “Your pet must be positive.” I got angry. It felt like I was talking to a stone wall.

I felt they had no right to come and take away my cat. Plus, she’s so little. She’s less than a year old. I didn’t care about myself, but I wanted to protect her. Even if they took me away, or punished me, I couldn’t let them harm my cat.

The community workers told me over the phone, “Think carefully. Is your cat more important than a human life?”

I’d read news about pets being harmed in the name of disease-control. I asked an online group of pet owners what I should do. Someone gave me the phone number for the Xuhui district CDC. They were quite friendly, but they didn’t give me a definite answer either. They just said, “In principle, nothing would happen to your pet.”

I was still worried. If the residential committee came in to take my cat away, I wouldn’t be able to do anything, since by then they’d also have taken me away. Jiumi, though, just kept eating and drinking. I told her, “Little cat, look at all these people worried about you! And what are you doing?” But she didn’t care. When she slept, she slept like a log.

The next day, I called the residential committee again. The person who answered the phone was quite rude. I decided to record this conversation for evidence.

A friend posted the recording of my call on Weibo, asking if anyone had a similar experience. Unexpectedly, the recording got shared tens of thousand times. The next day, someone from the subdistrict office called me and said they agreed to let me send my cat to a safe place.

-3-

A sigh of relief

The hardest part of the journey was from my apartment to the entrance of the compound. You need to let the residential committee know, and find a volunteer willing to take the delivery. There are not many people willing to deliver pets, especially from households with positive cases.

I called some pet-transportation companies, but they were overbooked. In the end, I used the Meituan delivery platform and added a tip of 50 yuan. I waited three hours before someone finally agreed to take the delivery.

I let out a sigh of relief.

I got transferred to a shelter hospital two days after sending Jiumi away. Even to this day, there are people still commenting under the Weibo post or privately messaging me asking how my cat is doing.

The groomer who is currently taking care of Jiumi at the pet shop has sent me some updates. “She’s very cute, and very active. She gobbles up all her food like a little tiger, and when she’s done, she takes a nap and snores away. When she wakes up, she’s full of beans again, and when she’s in heat she’ll start yowling.”

I think a lot of people who were worried for Jiumi were also worried for themselves. Nobody thought something like this would happen to them. They hoped that my experience would bring them some comfort. If I was able to send my cat to safety, that means there was hope for them.

Jiumi at the pet shop (Courtesy of Cara)

To this day, Shanghai has no clear rules about what to do with pets during the pandemic. Many communities still have the conservative attitude that pets are carriers of disease. I think everyone is worried that their community will harm their pets.

My suggestion is that as soon as you get diagnosed, remove your pets to a safe place, because you don’t know when you’ll come back. At home, your pet could run out of food, or they might tip over their own water bowl and run out of water.

Contact a pet shop ahead of time, and see if you can find a volunteer in your community’s chat groups for the crucial journey between your apartment and the community entrance. If you really have no other option, you can leave them at home, but make sure you leave enough food and water. You can turn on the tap a little so that it drips, and then your pet can drink from it if they run out of water or overturn their bowl.

Lock your door when you leave, and don’t give the residential committee your key. The people who come and disinfect your home are supposed to ask for your keys first. They have no right to break into your home.

The Xuhui CDC also told me I had the right to refuse disinfection. In that case, you are supposed to open your windows, or contact them to disinfect your home after you return.

I never thought this could happen to me, until it did. I hope everyone has the courage to go and defend their rights.

We haven’t done anything wrong.

Translated by Hatty Liu. Text has been edited for brevity and clarity.

___

This story is published as part of TWOC’s collaboration with Story FM, a renowned storytelling podcast in China. It has been translated from Chinese by TWOC and edited for clarity. The original can be listened to on Story FM’s channel on Himalaya and Apple Podcasts (in Chinese only).