As the pandemic ravaged China in late 2022, a family struggles with the decision to send a dying elder to overcrowded hospitals

1/8

In early December last year, following China’s rollback of its strict pandemic controls, both my mother’s sisters—my eldest and youngest aunts—were infected with the virus in close succession. There was a third person living under the same roof as them—my maternal grandmother, or Waipo, a dainty, elderly lady who was already 95 years old at the time and barely weighed 70 pounds. Soon enough, she also came down with a persistent fever and cough.

Waipo’s frail health predated her catching Covid-19. She had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease two decades ago, at the age of 73, and it had ravaged all memories of her own self, and of her relatives. For a while, she could still walk; she could easily go on for some two or three kilometers before anyone could stop her. However, that too came to an end five years ago, when she broke her left leg and never quite healed from her injury. Thus, the confines of her world were reduced to those of her narrow bed and her wheelchair. There had been a gradual deterioration of her leg muscles. Her legs themselves were now just bones covered by a thin, rough layer of skin resembling sackcloth. She wasn’t really able to keep her back straight, whether she was lying down or sitting up, so walking was out of the question.

Waipo had one son and three daughters. However, Uncle suffered from lifelong disabilities derived from hearing issues since his early childhood. He relied on sign language for daily communication, and though he did a great deal at the household, he spoke very little. He left all relevant decision-making to his wife and sisters and kept himself busy in the family home, including watching over Waipo. Once in a while, Mom and her sisters came over for a few days at a time to give Uncle and his wife a brief respite from their routine, so that they could go for a walk and rest. This went on until early last year, when Uncle was diagnosed with advanced bowel cancer. His illness and his own surgery and chemotherapy kept his family busy. Eventually, it was decided that Waipo would move into the suburbs with my aunts. My mom also lived in the area.

The situation was not easy on Waipo’s three daughters. All three were already retired and had their own lives to live. My eldest aunt hopped on a bus every afternoon to go pick up her own granddaughter from school, more than 10 kilometers away. Mom was a breast cancer survivor herself and still reeling from her own round of post-surgery chemotherapy three years ago. In fact, Dad was in charge of cooking in our household, because it took little more than merely lifting an iron pot to sap my mother’s strength. Eventually, my youngest aunt stepped up to take care of Waipo. After all, she had no grandchildren to take care of, seeing as her own daughter was single and busy with her government job in the city. Auntie’s husband had also reached retirement age, and they were both in good health, with plenty of free time.

Not only was my youngest aunt the best candidate to take on Waipo’s care; she volunteered before her sisters could even bring it up. She tidied up their study room, where she set up a brand-new nursing bed, the kind of model that can automatically turn you over and sit you up, as well as Waipo’s wheelchair and stacks of diapers, changing clothes, bedding, and more. All this she prepared before Waipo’s arrival. Some may regard caring for the elderly as a burden and a drag, but Auntie had nothing but a joyful, warm welcome for Waipo when she finally did move in.

—

However, Auntie’s many hurdles also began before Waipo fell sick with Covid-19. Her father-in-law was in critical condition with the virus, so her husband had to go take care of him. This left Auntie alone with Waipo, other than some occasional support from my eldest aunt and myself, in lieu of Mom, whenever my work would let me.

On these occasions, I would stay at Auntie’s house, feeding Waipo a light fruit supper before we plopped together in front of the TV to watch the music channel—her favorite. Once, I asked my aunt whether she ever felt caged at home in her new capacity as a caretaker. Was she bored now that Waipo’s care kept her away from her past routine of painting and guzheng lessons? But Auntie replied: “No, not at all.”

She followed her words with some revelations of her memories watching over her father’s deathbed in the ICU—my grandfather, Waigong.

I was still in college at that time. Auntie had been tasked with taking care of Waigong that day, but he just stared at her. Auntie felt something was off, so she got her face close to Waigong’s and whispered into his ear, “Dad, is something the matter?” However, at this point Waigong had already been intubated, so he couldn’t speak. He could only stare at Auntie. It finally dawned on her then, Auntie told me. She leaned in again close to her father’s ear and said, “You want me to take care of the family, right, Dad?” Waigong nodded vigorously. My aunt was taken aback momentarily, but then she immediately cracked a smile and reassured the ailing, elderly man. “Don’t worry, Father. I promise you I’ll take good care of everyone at home. I’ll look after Mother and Brother.”

Two days after his youngest daughter left his bedside, my grandfather passed away in the early morning. Auntie said that though she never forgot her promise to her late father, she never had the chance to honor it when it came to Waipo. Then, Uncle fell ill and she realized that it was the perfect chance to finally fulfill Waigong’s last wish. Thus, for over half a year, Auntie devoted herself to Waipo’s care. Thanks to her dedication, Waipo put on some visible weight and Uncle found the strength in him to battle against cancer.

So, even though she was now effectively trapped at home every day, mostly isolated from the world, my aunt said that she was rather happy with her lot. She’d finally been able to take on the heavy responsibility of looking after the most vulnerable members of our clan. She’d yet to tire of this alleged burden.

—

Now, Waipo was down with Covid-19. In her first week battling the infection, her body temperature oscillated between 38 degrees and 36 degrees, only dropping briefly when she took her medicine. Every time it wore off and her temperature went up, our family’s collective heart sank. We kept track of her condition in our WeChat group, with my aunt in charge of uploading nursing records daily: “Body temperature a.m. check: 37.8 degrees”; “I fed her two eggs and a bowl of milk porridge at 10 a.m.”; “Body temperature check at 2 p.m.: 38.3 degrees”; “She struggled to swallow her anti-inflammatory drugs, so we gave her a shot instead…”

On the 10th day of her fever, all Waipo could take was two spoonsful of water—everything else she refused. Auntie hurriedly call my mother, asking her to rush over and help. However, Mom was facing another family emergency. My paternal grandmother, Nainai had also been infected with the virus. Her high fever had never relented; her throat was irrevocably clogged with phlegm. Her condition declined steadily until she passed away on the night of December 25. At the time Auntie called, Mom was dealing with her mother-in-law’s burial arrangements.

Eventually, a family group call took place—on one end, my youngest and eldest aunts, now barely recovering from the virus themselves; on the other end, my mother. Being the middle child, Mom naturally had to pay heed to her eldest sister’s thoughts on the whole situation before voicing her own. Furthermore, as Waipo’s tireless caretaker, Auntie also took precedence over Mom on this particular occasion.

Dayi, my eldest aunt, said resolutely: “I’ve talked this through with Brother and his wife. Come what may, Waipo is staying here. We are not taking her to the hospital. Period.”

Auntie seemed less certain, and gave herself the floor before Mom could even reply. “What if this can’t be treated at home?”

Rather than answering directly, Dayi finally turned to Mom. In fact, my mother agreed with her. She thought Waipo was much too frail, what with being 95 years old and everything, to stand a chance at the hospital.

Dayi went on to share what she’d found online: “Hospitals are so crowded, apparently it takes hours now just to get a CT scan. Imagine parking Mother there for a full day while they stumble and fail to find the right treatment for her. She’d be done for, for sure.”

Mom said her mother-in-law never went to the hospital. She’d been under the care of my paternal aunt, who held Dad in great regard and respect as the eldest son and therefore followed his instructions on how to proceed should Nainai reach a critical condition. “If her time comes, let it be in the comfort of her family home.” When this moment came indeed, Nainai passed in the arms of her daughter at home.

Auntie is not a strong-willed person, and she found it much too hard to reason against her two elder sisters. In the end, she reluctantly and somewhat passively agreed that they would not send Waipo to the hospital.

2/8

Two days later, early in the morning, we rushed to our hometown in the mountains to proceed with Nainai’s burial at the family’s ancestral grave. It was just before noon when I received a message from my youngest aunt. After three consecutive days of refusing food and drink, Waipo’s belly had shriveled up; she could tell as much whenever she took her clothes off. “What should we do?”

For the past six months, Auntie had been Waipo’s main caretaker. Every couple days, I’d visit them, taking along some sweet treats I’d bought on the way. There, I’d chat with Auntie and listen to Waipo’s now unintelligible speech. Perhaps without even noticing, my aunt had come to trust me as much as she would her two sisters. Faced with her predicament, she was now pinning her hopes on me.

Deep down, Auntie probably never really gave up on the idea of sending Waipo to the hospital. With this call for help, she wasn’t so much asking for advice as she was trying to gather her courage—or rather, trying to convince herself.

I could understand why Waipo’s children were reluctant to send her to the hospital. Both Waipo and Nainai were well into their 90s; both suffered from Alzheimer’s disease. Nainai had been known to call her son “Father,” just like Waipo now would often mistake her youngest daughter for the eldest. Neither had even been able to speak clearly in the last few years; their speech had been reduced to mere indiscriminate noises. They’d lost all semblance of what we call “quality of life,” and they depended entirely on round-the-clock care from a healthy family member who could never, in turn, leave their side. One second away was all it took for them to go have a drink of water from the toilet or burn the sheets with a lighter; such actions were not unheard of from Alzheimer’s patients.

With each passing day, family bonds were further eroded by the intensity and fatigue of caretaking duties. This final Covid-19 crisis had only compounded the situation; my own aunts had been infected one after the next and couldn’t even take care of themselves. Taking our elders to the hospital would not only prove lethal for the elders themselves—it would also be taxing for their children. Faced with such dire straits, they felt it was best to self-medicate at home, minimize the risk to the family as a whole, and let nature take its course.

I had also been silently struggling with an urge to send Waipo to the hospital. Eventually, I called Auntie back. When I asked her what her plans were, there was silence at the other end of the line for a full minute.

When my aunt finally spoke again, she simply asked: “Can we just take her to the hospital?”

I was lucky to find an ally in Auntie. Perhaps after the sudden death of Nainai, I was just haunted by the nightmare of losing two grandparents, one after another. Yet, I was the grandchild, and I had to obey my elders, especially when it came to such an excruciatingly sensitive matter.

Even so, I still felt uneasy about risking the lives of Waipo and even other family members. I told Auntie: “We should try, as long as we can prepare for the absolute worst case scenario.”

She’d fallen silent again, as though she was weighing each possibility herself now. Eventually, she burst out in sharp, harsh sobbing at the other side of the phone. “I just don’t have it in me to do nothing, to simply sit down and watch her die like this…” For a while, her sobs continued until she regained a modicum of strength and I heard her voice again. “Alright, let’s give it a go. Even if we don’t save her in the end, at the very least we’ll have tried our best, right?”

That’s when I knew there was no turning back. We were now about to cause the biggest split our family would face that winter.

3/8

I hung up the phone and immediately rang up my parents to tell them about our idea of sending Waipo to hospital. Just as I’d expected, I was met with disapproval from both of them. Mom accused Auntie of taking things too far: “She’s making things difficult for a child.” Dad was more concise. “I do not support taking her to the hospital.” Mom doubled down: “This has already been discussed. Don’t let your aunt pester you with her nonsense.”

I remained silent.

As I drove my folks home from Nainai’s funeral, I still didn’t have it in me to defend either Auntie or myself. My one and only argument was that if Waipo were to pass away right after Nainai, arranging a second funeral would deplete their health. All I wanted was to buy the family some more time to regroup, even if it was just a night or two. “I just don’t want to see anyone else in this family falling down again.”

Much like I couldn’t get any support from my parents, Auntie couldn’t get any approval from her elder sister either. Lately, they’d been living together to manage Waipo’s care, and so Auntie told her about our conversation as soon as she hung up our phone call. To this, Dayi replied sarcastically: “Ah, yes, sure! Go, just go to the hospital, right away!”

My youngest aunt took this at face value, so she got down to packing immediately. My eldest aunt gave her a cold stare as she rushed searching for Waipo’s necessities—enough clothes for her stay, diapers, changing pads, water cups, all sorts of stuff.

When I parked downstairs, still with my parents in the car, Auntie asked her elder sister to help her carry Waipo from the bed to the wheelchair. Dayi scoffed at her: “I’m not following you to the hospital.” Auntie swallowed her retort as she put both her arms around Waipo, lifting her onto the wheelchair.

As soon as I put Waipo in the car, Dayi left us and turned around to leave. I tried to call her, but she didn’t even look back as she cut me short. “I’m going home.” Auntie tried to persuade my mother to go with us in the car, but she stood calmly with my father side by side on the road.

Nobody was arguing, and yet there was an invisible barrier between us. We were now separate factions.

I tried to excuse my parents. Surely Nainai’s burial preparations had exhausted them over the previous days. Guileless as she was, my youngest aunt actually believed me. She said goodbye to her sister and brother-in-law and immediately got into the car, where she covered Waipo’s head with one hand as she wrapped her injured leg with the other. All the while, she muttered: “Lean on me, Mom! Yes, right on my body, just like that. I’m holding you.”

From the rearview mirror, I saw that Waipo was pretty much unconscious. Though she probably couldn’t hear anything, Auntie kept telling her over and over again: “Mom, we’re going to the hospital right now. Be patient. We’ll be there soon and then you’ll get well.”

My aunt had not called Waipo “Mom” for a long time. In fact, she’d called her “Old Chen,” as if she was addressing an old friend. This maybe helped her grapple with the reality that Waipo lived her days in a haze of dementia where she could no longer remember their mother and daughter bond, let alone cherish it. The way my aunt saw it, calling for “Mom” and not getting any response would have exacerbated her feelings of sadness and loss. “Old Chen” being unreachable? Much easier to handle.

It took us an hour to drive to the hospital, and Auntie spent at least half of that time bawling her eyes out. She was like this wronged child that had finally seen her parents and wanted to vent all of her emotions to them, all at once.

She was the one who took care of Waipo all day, every day, Auntie said. She was the cook, the one in charge of changing diapers and bath time. “Why do I have to suffer from a guilty conscience after all the dirty work I’ve done?” Auntie had been by Waipo’s side day after day; she’d seen her grow weaker and sicker with each passing day, too. Finally, there was only a trace of life left in her, and she hung by this very thread. “This would be unacceptable to do this to a perfect stranger, let alone my mother. I really can’t—I really can’t let her fend for herself.”

I remained silent in my role as a listener. I figured with nobody to talk to, she’d been bottling up all these words in her heart for a long while.

4/8

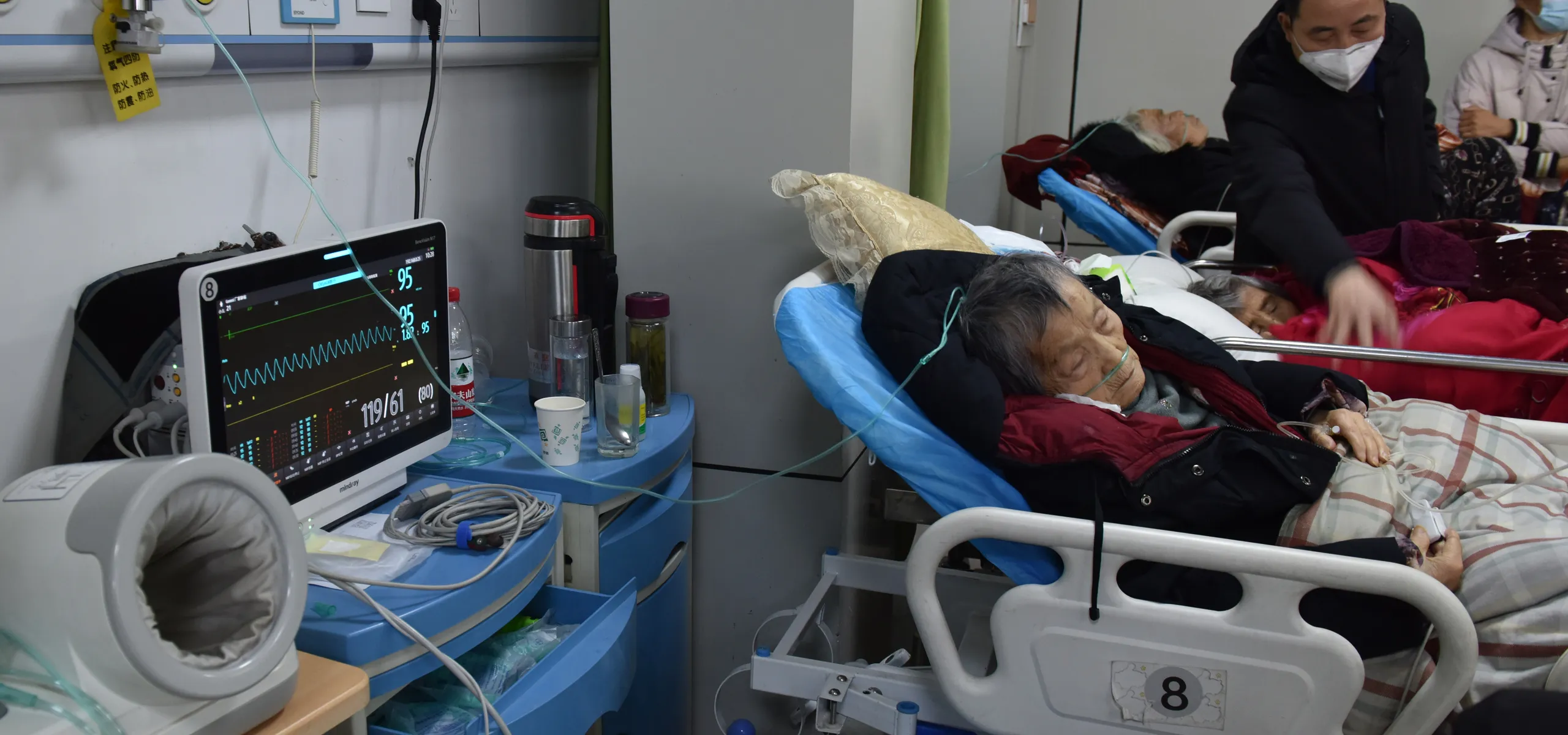

A painful day and a rough night tow were waiting for us at the emergency room of the hospital.

Both inside and outside of the ER, we were met by huge crowds. Every step we took in the hospital took what seemed like hours—from registration to every medical treatment, laboratory tests to infusions.

Most of the patients looked much like Waipo: pale and sickly. They sat on wheelchairs topped with colorful quilts; they were guarded by two or three family members, usually their middle-aged, sallow-looking children. Even for those who were not battling an infection or fever, staying packed for just a few hours in such an airtight, crowded, and noisy space would be sure to sap anyone of their energy.

We waited for three hours before finally getting Waipo’s test results, and even then the doctor just pointed out in surprise, “She is truly in critical condition, why did you come here?”

My aunt and I looked at each other. The doctor explained: “If you had come here just a little later, the patient would have faced cerebral death.”

I looked at my aunt again. I didn’t know whether we should feel thankful or guilty.

We spent the night in the ER. Waipo was plugged to a gastric tube via her nostrils, and her wrist was jabbed with an IV. Every 15 minutes, my aunt and I took turns handling a syringe to inject 20 ml of water into her gastric tube in an attempt to relieve Waipo from her severe dehydration. My aunt produced a hardcover notebook and a pen from her bag to record every time we got her water, changed her bottle, made sure she inhaled oxygen, and helped with the machines. The doctor’s orders were to inject Waipo with 2,000 ml of water that night, so we had to pump the gastric tube 100 times. Auntie made a large mark on the top column of the notebook for that 2,000 ml figure, wrote each time node in advance and proceeded to tick one check at a time. She looked as though she was conducting some serious experiment, or maybe a solemn ritual.

The next morning, Waipo was out of immediate danger and her condition had improved noticeably. However, now it was Auntie who was coughing violently after a night deprived of sleep. I was feeling dizzy myself. We got a couple calls from Mom and my eldest aunt to check on Waipo during this period, but that was all; they did not even bring up the possibility of relieving us at the hospital.

Auntie and I had run ourselves ragged over the past couple days. Ironically, this was precisely the situation that my parents had been worried about. However, I still think we made the right call. It was just really tough to persevere without the appropriate backup and supplies.

After the follow-up visit from the doctor that day, I offered to take Waipo home to complete the round of infusions. The hospital was strained for resources, and it was hard to get a bed. Elderly patients like Waipo required nursing care, which took up manpower. In short, the doctor was happy to have us take her home to relieve the burden on the hospital.

After getting Waipo’s medicine, I drove her and Auntie home. My aunt was so sleepy that her eyelids were twitchy, but she worried that I’d fall asleep on the road, so she still talked to me from time to time.

After relocating Waipo to her nursing bed at home, my aunt and I slumped into our chairs, seemingly free from our hefty burden. But this was a mere illusion. Our nerves were throbbing violently, and so were our heads out of sheer sleep deprivation.

Soon after returning from the hospital, I came down with a fever as well, and I was too ill to leave the house. My parents also got sick soon after returning from Nainai’s funeral. As for Dayi, she never returned to Auntie’s place to lend a hand. My youngest aunt was left to her own devices in her empty, three-bedroom house. Once again, Waipo’s care was all on her.

Those who left didn’t ask; those who stayed behind didn’t tell. Both parties pretended everything was fine. However, some two weeks after returning from the hospital, Auntie collapsed.

5/8

At quarter past nine that evening, I got a total of three voice mails from my aunt. She was concise, but her voice sounded weak: “Hey, I have a headache from hell. Could you come over and help me take care of Waipo?”

While I got dressed to leave, I informed Mom about the situation. She immediately sat up in her bed, and raised her voice over the video she’d been watching: “Why is she always dragging the child into her problems?”

All I said was that she could call Auntie herself. However, my mother’s expression tensed immediately after my aunt’s hysterical crying came over the phone. She finally calmed down enough to utter a few complete words. “My headache… Too strong… It hurts… Too badly.” Then, she started weeping hysterically again.

Realizing that the situation was serious, my parents and I drove to Auntie’s house together. On the way, we ventured that maybe Waipo was dying; maybe this was the reason behind Auntie’s hysteria. However, Waipo was not on her deathbed. If anything, she seemed to be in good spirits—eyes wide open, even raising her eyebrows at me a few times, muttering strings of monosyllabic words. My aunt, though, was a different story altogether. We found her curled up on her bed, head on the mattress, lights off. In the darkness, she looked like some kind of pitiful, lurking creature licking her wounds.

I rushed over to hug Auntie and held her head. Before I could even check on her current state, I realized that my hands were wet and slippery with the tears that still rolled down her cheeks. The fine lines around her firmly shut eyes had been scrunched into a tight net that made her look much older than her actual age. She was obviously still in pain, and yet the first thing she said to me was, “It’s 10 o’clock, isn’t it? Time to get your Waipo some water.”

I reached out to grab the thermometer that I knew was usually on the bedside table and passed it to my aunt, urging her to check her own body temperature. Meanwhile, I got up and headed to Waipo’s bedroom, where I carefully pumped water into her stomach tube, noted all the details in the hardbound notebook, and picked a few cotton swabs from the small box on the bedside table, which I wet and smeared on Waipo’s lips and tongue. I had long memorized the entire process; I was going through the motions.

My aunt had rarely suffered from headaches before. I checked her blood pressure; it was twice as high as usual. She gave it a look and said, “No wonder it hurts so much. It’s like a pressure cooker about to explode.”

“Why did your blood pressure spike like this?” I asked. “What did you do?”

Auntie rubbed her temples for a bit before she disclosed her worries that Waipo wouldn’t live through the night. The more my youngest aunt dwelt in these thoughts, the more frightened she became. She’d wanted to turn to her sisters, but their previous attitude intimidated her; she was reluctant to call her husband, too. He was busy with his father, now fighting a high fever as well. At the end of her tether, my aunt fell into a vicious circle of fear and worry that eventually exhausted her nerves, and her blood pressure skyrocketed.

Mom sat by Auntie’s bed and chided her. “Really, you are asking for trouble.” The way my mother saw it, this was all due to our insistence on sending Waipo to the hospital. The gastric tube from the hospital was yet another worry to add to our plate. Plus, had we kept Waipo at home, my eldest aunt would have stayed around to lend a hand, so that Auntie didn’t have to brave the storm on her own.

Dad followed suit. “Waipo is very elderly already. She may pass away at any time. How can you not be mentally ready for this already? Why did you get yourself into such a state?”

Auntie wouldn’t budge.

Honestly, I completely understand my folks at that moment. They didn’t think they were being harsh at all; in fact, they were behaving the way any rational, calm adult should have. They saw Auntie as this somewhat impulsive naïve creature who could be easily deluded by emotions.

“Okay, okay!” Auntie suddenly let go of her hands, and her messy hair fluttered about. “It’s all my fault! I was the stubborn one who set on sending Waipo to the hospital! I insisted on playing savior! I gave myself a good scare! Yes, yes! It’s all on me! I brought it all on me!”

It was obvious that she was peeved.

“Have you seen her suffer? I have. Have you seen her hands all stretched out at night, just like she was trying to grab something from the ceiling? I have! And, I know that she wants to live. She really does! When she’s running a fever, she looks at me with this longing in her eyes. I keep my eyes on her every single day, I keep track of every single detail about her daily routine. Those eyes of hers, I am telling you—that’s not her usual gaze. Her eyes are telling me that she yearns to live.”

My aunt grew increasingly agitated with every word, and it didn’t take long before her headache took over again and the tears streamed down her face. Her voice broke and I rushed to stroke her back repeatedly, reminding her to take deep breaths. Though the migraine did eventually subside, Auntie was now listless on her bed. Her eyes seemed hollow from all the pain she’d endured. Still, she turned to my parents and said: “If you’ve also noticed it, you’ve got no business to insist on being rational.”

6/8

Following Auntie’s emotional breakdown, I now had to spare a couple hours daily to drop by her place and keep her and Waipo company.

Mom had softened quite a bit, too. Sometimes she joined me on my visits; she would talk to Auntie too. However, she still had to save face, so she’d make a point of mentioning my aunt’s “betrayal” from time to time.

Just like that, a week went by peacefully. As we gradually left the whole incident behind us, we thought that Waipo’s condition had actually improved quite a lot. Then, trouble returned.

I’d just visited to help with Waipo’s treatment. Everything seemed normal: Waipo was even somewhat chatty in her own limited way. In the afternoon, though, Auntie called all of a sudden and the trembling in her voice immediately made us realize that the situation was far from good.

Just as we rushed over, my aunt called again, this time with the camera on. On the mobile phone screen, we got to see Waipo’s convulsive, uncontrollable trembling seizing her entire body from her hands down. I could tell Auntie was terrified. She kept repeating: “Call an ambulance. Call an ambulance.”

Mom didn’t reply. I turned to look at her and I was just as aware that she was hesitating again on whether we should take Waipo to the hospital now. Once again, I stood up and gave her a push. “Mom. Mom, let’s call an ambulance.”

This time, I caught the panic in my mother’s eyes. As it turned out, Auntie had a point—rationality went out the window when you really saw the end approaching.

Mom nodded to me first and then to Auntie on the screen, signaling her agreement to send Waipo to the hospital.

The ambulance whizzed her directly into the ER, unconscious and with a fever reaching 39 degrees. The doctor said that her situation was “critical.” Not only did Waipo’s condition not improve in the slightest after being rushed to the hospital; Auntie’s headache came back. It was, as she described it, “like a hand scratching around inside her skull.” At a certain point, she was in so much pain that she lay on the bench outside the emergency room, eyes closed.

Finally, for the first time after their initial fallout, my eldest aunt met her youngest sister again. However, she didn’t have a single greeting or expression of sympathies to spare. She watched the scene from a distance, like a stranger. Meanwhile, Auntie had to be checked in for medical treatment herself. The doctor checked her test results and concluded that they’d need to infuse several bags of medicine into my aunt to temporarily lower her blood pressure.

That night, Waipo got her medical infusion in the ER, while Auntie got hers in the infusion unit upstairs. One mother, two daughters, and not one cared for the other. My mother had thrown her back out on our way to the hospital and could neither sit nor stand in the ER, her face pale with pain. When I told her to go back home, my eldest aunt saw her chance to leave, claiming that she also suffered from back pain.

In the end, just like the first time, it was just Waipo, Auntie, and me left in the hospital.

—

Auntie was finished over at the infusion unit in the early morning and seemed to regain some of her energy, so she sneaked in to check on Waipo while the ER doctors and nurses were out. Waipo’s fever had subsided under the effect of her medication, but she was still unconscious and her eyes were closed.

With her own hand just barely free from the infusion needle, Auntie stroked Waipo’s forehead before bending down to press her forehead close to hers. This had been a small, intimate ceremony for mother and daughter every day, every morning. Auntie greeted Waipo by her bedside, their foreheads touching ever so gently to mark the start of a new day.

However, this time their affectionate ritual was followed by a soft apology. “Mom, I’m sorry.”

Later, I found that this was a turning point for Auntie. She finally realized that while her sisters’ previous decision may not have been right, it was still the most sensible. As she gradually healed from her own health emergency, my youngest aunt realized that there was more to her sisters’ choice than cruel realism—it was also the one inevitable, helpless course of action left for them.

—

Faced with the rampant spread of the virus, the hospital did not allow relatives to visit or even stay by the bed of their inpatient loved ones. In this second hospital stay, Waipo was cared for by several nurses, and our family enjoyed a peace that we’d long lost.

The hospital tried to persuade us to take Waipo home with us. They had no beds, so she couldn’t be transferred to the general ward. However, the hospital couldn’t just kick her out, either. They could only send the doctor to “advise” her relatives to take her home.

This time, though, Auntie and I were willing to be selfish. Waipo staying put in the hospital granted her medical care, something that we could no longer guarantee for her at home. There wasn’t another person in our family who wasn’t either sick or barely recovering from Covid-19. If Waipo was the garrison our family guarded, our army had long been wiped out.

It’s not like Auntie really got a break from her migraines, either. She didn’t want her daughter to know, nor was she willing to burden her husband with her care, so she went to seek treatment at several hospitals on her own. At that time, my cousin had yet to test positive; she was busy with work and far away from home. Moreover, she was the baby of the family, so nobody expected her to come help, let alone blame her for being absent. Auntie’s daughter was regarded as a kid who had no business meddling in the affairs of adults.

So, we kept pretending we didn’t catch the hospital’s hints. Even though the doctor’s attitude toward us was extremely cold every time we went to check on Waipo’s condition, we all planted this polite smile on our faces. After all, Waipo was safest in their care.

7/8

And then, just when I assumed Auntie had found peace with her decision, she proved me foolishly wrong.

Three days before the Lunar New Year, I went to Auntie’s place to pick up some stuff. I hadn’t been there since Waipo had been admitted to the hospital. Everything remained unchanged, other than the fact that someone had drawn back the long, hanging gauze curtains that filter sunlight out from the living room and turn it into a dark, gloomy space.

As it turned out, Auntie was sitting on the sofa right next to the curtains, with her gaze fixated on the mobile phone in her palm, even though the screen was locked. As I changed my shoes, I knew something was wrong with her. She hadn’t even acknowledged my presence.

The room was awfully quiet, and I was afraid of startling her. So, I called her softly as I approached the sofa, one step at a time. After the third call, Auntie seemed to finally snap out of her spell to look at me. Even then, she still seemed somewhat stunned. “Why are you here?”

“Mom told me to come pick up this and that,” I tentatively said. “I just arrived.”

“Ah, that’s right. Right, right, right.” My youngest aunt started to get up, but then fell right back into her daze. She asked, “Are you in a hurry for work? Busy?”

I shook my head. No, not busy. I’ll just go straight back home later.

Then, Auntie looked at me and asked, “Could you stay for a bit to chat?”

It was the first time in my life she’d ever asked me anything like this. Our relationship this month had undergone subtle changes as we fought side by side. In my eyes, Auntie was no longer just my elder; she was also a comrade-in-arms, a friend. So, I took off my coat, sat on the sofa next to her, and poured her a fresh cup of hot tea.

These days, she told me, she kept herself busy thoroughly washing Waipo’s sheets, quilt covers, and pillowcases. In fact, she dried them just as meticulously, as she made sure to point out on the balcony at the end of the bedroom directly in front of her. “Look at that quilt. It’s been hanging there for a few days already.”

That’s when I understood. “Auntie” I asked. “You still want to bring Waipo home, right?”

She replied with a question of her own. “You reckon she wants to come back home?”

I had other concerns in mind, though, and I didn’t try to hide them from her. “Who’s going to take care of Waipo if you bring her back?”

My aunt looked at me silently for two or three minutes. Then, she mentioned that she’d just been talking to a friend in hospice care about our family crisis. Auntie’s friend refused to dish out any judgment and simply asked her, “Is your mother suffering right now?” My aunt gave it some thought before replying that, though she couldn’t be as comfortable as she was at home, at least she was getting medical care. Auntie’s friend went on to ask a series of questions—was Waipo intubated? Was she getting daily infusions? Was she hooked up to an oxygen machine? Was she bedridden?

At this point, Auntie turned to me and asked me all of a sudden, “Does that qualify as suffering? If we hadn’t taken her to the hospital, we wouldn’t be talking about this daily ordeal we’re putting Waipo through. Intubation, poking and prodding her endlessly with needles, a breathing mask on at all times, no food, no drink.”

“Auntie,” I chimed in, “with her fever the way it was, she’d have suffered if we’d let her stay at home, and she most likely wouldn’t have survived.”

Auntie suddenly grew agitated. “Had she died, like your Nainai, wouldn’t it have been better? All her suffering up to this point, in vain. She can’t recover. What a waste of time.”

As Auntie spoke, the pity in her eyes mirrored my own. “Are we too selfish? It’s not like we ever asked her for consent when we shipped her to the emergency room to rot there.”

“Auntie.” I placed my hands on her slightly trembling knees, as if to pin down her agitation. “Waipo cannot speak. Waipo cannot think. She only has us to make decisions for her. You’re fixating on her feelings, but our decision can’t depend on that alone. You say we’re selfish, and I’m not saying you’re wrong. What I’m saying, I guess, is that we couldn’t help it.”

In fact, when I decided to back her plan to send Waipo to the hospital, each and every reason I had to offer was “selfish”—I couldn’t bear the thought of letting go of Waipo, even though it had been two decades since the last time she ever called my name. I was still reeling from losing Nainai. I wanted my parents to enjoy a brief respite, too, and I hoped to achieve that by having Waipo linger a few more days. And, last but not least, I didn’t want Auntie to be filled with regret and guilt after all she’d done for Waipo.

“Actually, Auntie, on the day we had Waipo admitted, I waited for you to go to the registration desk and said something to her. I told her, ’Waipo, I’m sorry. I’m so selfish, and I miss you so much. All I can do is have you stay here for a while until the moment comes.’” All of a sudden, I could feel the warmth from my own tears welling up. “Auntie, blame yourself for actions in your past. We are not Waipo, so we cannot take her suffering on us. Each of us has a burden to carry. We cannot do everything. We can only try and make sure her last days are as comfortable as possible.”

My aunt looked at me with a dazed expression for a short while, then replied, “You mean, we should try and relieve her pain?”

I nodded.

Auntie had never really considered this option; it was perhaps a bit too bold. She asked worriedly, “But, would it be life-threatening?”

I replied that even if she were to remain intubated, Waipo just didn’t have much time left all the same. “Her lungs are infected and her heart is really damaged too. The doctor said that her life is at risk at any given time, every day. We can wait and wait for her to drag on, delaying what’s bound to come, or…”

Now, Auntie was following me. “…Or we could let her spend a few precious, final days in the comfort of her home.”

I nodded again. This was probably the very last thing we could do for Waipo.

8/8

In the end, we didn’t get the chance to carry out our plan. Waipo passed away in the hospital.

Auntie had talked it through with her brother-in-law and her two sisters. We wanted Uncle to finish his last round of chemotherapy, so we intended to have Waipo’s tube removed after Lunar New Year. Then, we’d take her home and remain by her side for her last few days, all together. However, on the night of the second day of the Lunar New Year, we got a call from the hospital. Waipo was now on her deathbed.

We rushed to the hospital, only to bid our farewell to Waipo via video call. She had on a heavy, bulky breathing mask that covered her face from her chin to the space between the eyebrows, including most of the surface of her tiny cheeks. The doctor told us she hadn’t opened her eyes for a whole day now. I called her name, and so did Auntie. After a few attempts, Waipo finally gave us a glimpse of her black eyes through the screen. It dawned on me then that this was really the last time she’d ever look at me.

Twenty minutes later, Waipo took her last breath. The doctor reassured us that she had not suffered in her final moments; one last, light gasp and she was gone, resting in peace. How great it was to know that her struggle had finally come to an end.

Auntie still took the initiative with all things concerning Waipo’s funeral arrangements. She had yet to recover from her recurring headaches, so she tended to everything from the hospital. The funeral also kept the three sisters in constant contact. Perhaps because they were consumed by their sorrow, their feud came to an end. They sat together, took their time, and talked to one another in a calm, rational manner. They also continually deferred to one another. “It’s up to you, do as you see fit.”

Waipo is probably happy to see this all from heaven. I hope she can remember her life now; I hope she’s gained back all her memories of her children and grandchildren. But I also hope that she’ll be able to forget it all, shed her past and start over from scratch. In fact, it shouldn’t make any difference whether she remains my Waipo or not, wherever she is now, as long as she is free and healthy. Whatever comes next for her, I want her to gallop into the vast world, with nobody to hold her back.

Written by Yin Xi (殷夕)