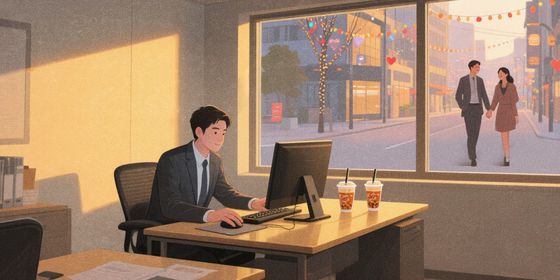

Chinese youth are identifying with the struggles of the protagonist in Lu Xun’s “Kong Yiji,” as they face unemployment and limited job prospects despite their education.

China’s younger generation has adapted an old literary character for a new dilemma: Kong Yiji (孔乙己), the protagonist of a short story by the same name by renowned 20th century writer Lu Xun, is a learned scholar who is unable to find work due to his impractical skills. The character has recently gone viral in China’s cyber community among highly educated youths, who relate to his struggles with unemployment and academic limitations.

Lu Xun’s story is set in the early 20th century, when the imperial examination (科举 kējǔ) system had just been abolished. Kong is one of the poor intellectuals who had studied the classics for most of their lives but failed the examination. Despite carrying himself with a scholarly demeanor, he lacks the ability to make a living and is unwilling to engage in physical labor to make money. Lu Xun used this character to illustrate the obsolescence of people educated through the imperial examination system and the tragedy of Chinese intellectuals in the late Qing dynasty (1616 – 1911).

Calling themselves “modern Kong Yijis (现代孔乙己 xiàndài Kǒng Yǐjǐ),” many of today’s youths have similarly spent most of their lives struggling for a diploma, only to end up jobless due to a recent shortage of work for young college graduates. According to the Communist Party Youth League, the number of students graduating from college is expected to hit 11.58 million this year. Most will have studied under quarantine and lockdowns for three years due to the pandemic, only to face what they call “unemployment upon graduation (毕业即失业 bìyè jí shīyè)” during the “toughest graduate season ever (史上最难毕业季 shǐshàng zuì nán bìyèjì).”

In Lu Xun’s story, one scene set in a tavern portrays customers wearing long shirts, who are upper-class people allowed sit down to drink, while lower-class people wear short shirts and can only stand and drink outside. Kong Yiji, as a failed scholar, is the only person wearing a long gown in the scene, yet he drinks his wine standing—the contradiction reflects his pathetic fate.

Similarly, many young netizens are now struggling with the dilemma of facing unemployment or accepting menial jobs or low-paid gigs that are not commensurate with their qualifications. They use “Kong Yiji’s long gown (孔乙己的长衫 Kǒng Yǐjǐ de chángshān)” as a metaphor for their “academic shackles that cannot be removed (脱不掉的学历枷锁 tuōbudiào de xuélì jiāsuǒ).” The Kong Yiji meme began with a small group of people sighing online: “A high education background is like a pedestal I cannot step down from, and a long gown Kong Yiji cannot remove (学历是我下不来的高台,更是孔乙己脱不掉的长衫 Xuélì shì wǒ xiàbulái de gāotái, gèng shì Kǒng Yǐjǐ tuōbudiào de chángshān).”

Netizens soon termed this kind of writing “Kong Yiji Literature (孔乙己文学 Kǒng Yǐjǐ wénxué)” and created increasingly cynical quotes about today’s education sector. One quote in particular gained popularity: “If I had not received an education, I could have found other work to do, yet I insisted on getting an education (如果我没读过书,我可以找别的活做,可我又偏偏读过书 Rúguǒ wǒ méi dúguò shū, wǒ kěyǐ zhǎo bié de huó zuò, kě wǒ yòu piānpiān dúguò shū).”

Some graduates who were brave enough to take off their long gowns and accept blue-collar jobs shared their experiences on social media. One wrote, “Low-level jobs do not require lofty degrees. Only when I changed my education background to ‘high school graduate’ could I find a job washing dishes (找底层的工作不要高学历,只有把学历改成高中毕业才有了一个洗盘子的工作 Zhǎo dǐcéng de gōngzuò búyào gāo xuélì, zhǐyǒu bǎ xuélì gǎichéng gāozhōng bìyè cái yǒule yí gè xǐ pánzi de gōngzuò).”

As a result, graduates have begun to question the value of “involution” and striving for higher education. Rather than “education being second to none (万般皆下品,惟有读书高 wànbān jiē xiàpǐn, wéiyǒu dúshū gāo),“ as was the saying in Kong‘s lifetime, some netizens today go so far as to declare that “education is useless (读书无用 dúshū wúyòng).”