Saving China’s national animal from extinction has meant moving thousands of people and creating new industries

Gu Xiang has lived on China Panda Avenue for 15 years, but he’s never come close to China’s national animal. “I was born and raised in Sichuan, but I’ve never even seen panda poop,” the 35-year-old tells TWOC.

That hasn’t stopped the black and white, bamboo-munching bears from leaving their mark on his village, Maoshui—not just by lending their name to roads. In fact, Maoshui and its residents were moved to their current location in part to aide the conservation of giant pandas, most of which live in Sichuan province in China’s southwest. The village used to be deep in the mountains, and pandas would even occasionally roam around the neighborhood, Gu claims.

But since the Wenchuan earthquake in 2008, residents were moved to a newly built settlement sandwiched between Wolong National Nature Reserve and Sichuan Fengtongzhai National Nature Reserve, partly to make more space for pandas in their habitat. Though tourists now flock to the panda-themed town, where Gu owns a restaurant, the bears never turn up here.

In Sichuan, one of the most biodiverse provinces in China, protecting the habitat of the country’s most famous animal means altering the lives of thousands of people who call the area home.

Though giant pandas only became widely known outside of China in the 19th century, there are many references to the bears in Chinese history. The first known records date back to the Zhou dynasty (1046 – 256 BCE), when they were described as “貔 (wild beasts)” in the Classic of Poetry (《诗经》) and as “白罴 (white beasts)” in the Book of Documents (《尚书》). They were also recorded in ancient literature like The Classic of Mountains and Seas (《山海经》) from the Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE).

French missionary Jean Pierre Armand David is credited with bringing the panda to wider international attention when he brought a specimen back to Europe in 1869. Soon after, Europeans and Americans began hunting the animal, with the help of locals—Theodore Roosevelt’s sons famously killed one.

Deforestation and construction also destroyed much of the giant panda’s habitat, and formed barriers in its territory that left many populations isolated and reduced their chances of finding a mate. According to a survey by the Bazhong Forestry Bureau in Sichuan, for example, the construction of the Baocheng Railway between 1950 and 1980 destroyed around 100 square kilometers of panda habitat.

The panda population decreased quickly, and it wasn’t until 1962 that China’s State Council finally announced a ban on hunting them. By the time of China’s first national giant panda survey conducted from 1974 to 1977, there were 2,459 pandas left in the wild. The second survey, from 1985 to 1988, saw the number decrease to just 1,114. In 2008, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) classified giant pandas as “endangered” on its Red List of Threatened Species.

The decline eventually brought a reaction, with the establishment of Wolong National Nature Reserve, the country’s first giant panda reserve, in 1978. Wolong and subsequent reserves aimed to reduce the impact of human activity on the pandas, restricting activities including logging and farming, and many locals moved out of the reserves to new homes.

People Out, Pandas In

As of 2019, Sichuan has 95 nature reserves, mainly to protect giant pandas, covering 113,500 square kilometers—nearly a quarter of the province. According to Gao Fuhua, a 58-year-old writer who calls himself a “panda journalist” in Baoxing county (where David, the missionary, first came across giant pandas), 82 percent of the land belongs to the Giant Panda National Park that is home to 181 pandas. That leaves the county’s human population of 50,000 sharing the remaining 12 percent.

“Ecological migration,” as authorities call the movement of residents out of conservation areas, has been a key pillar of panda protection methods in Sichuan. In 1983, for example, 800 residents moved out of the Tangjiahe National Nature Reserve and into new villages built outside the park.

The arrangement forced locals to find new ways to make a living. “The local people made great sacrifices to the nature reserve,” says Diao Kunpeng, who has worked at the Tangjiahe Giant Panda Conservation Station for the past 10 years, and often gets complaints from locals who moved out of their homes. “People had lived there for generations and were used to hunting and collecting wild herbs to make a living,” he explains. The reserve prohibits logging, farming, and hunting, while locals can no longer forage in the mountains.

“The best quality tianma [the herb gastrodia elata] grows at high altitude in the mountains, which now all belongs to the nature reserves,” an ethnic Tibetan ranger named Bonao in Tangjiahe tells TWOC. “When I was young we often went to collect tianma; for many people it was considered their main income source,” she says, referencing how locals would sell the herb for use in traditional medicine.

The local government and NGOs try to bring area residents (which include many ethnic Tibetans and Qiang) into conservation efforts: employing them as rangers (like Bonao), for example, or training them to be guides for research teams. Authorities also encourage the region’s traditional honey bee farming, as it doesn’t require cultivation of the land and is environmentally friendly.

Where some people remain, as in the Wolong reserve in Aba Tibetan and Qiang Autonomous Prefecture, local authorities have strict rules on activities in protected areas. Wolong was designated a special administrative district in 1983, with the district authority granted power to punish crimes such as poaching and illegal logging (power normally reserved for provincial-level departments). Authorities also offer incentives for locals to protect the environment, such as subsidies for electricity if they limit the use of firewood.

Can people and pandas live together?

“Sichuan is a province with many people and very little land. It’s not easy to set up a pure ‘no-human’ reserve for giant pandas,” says Gao. “Is the ultimate goal really to cut off the relationship between giant pandas and the human community?”

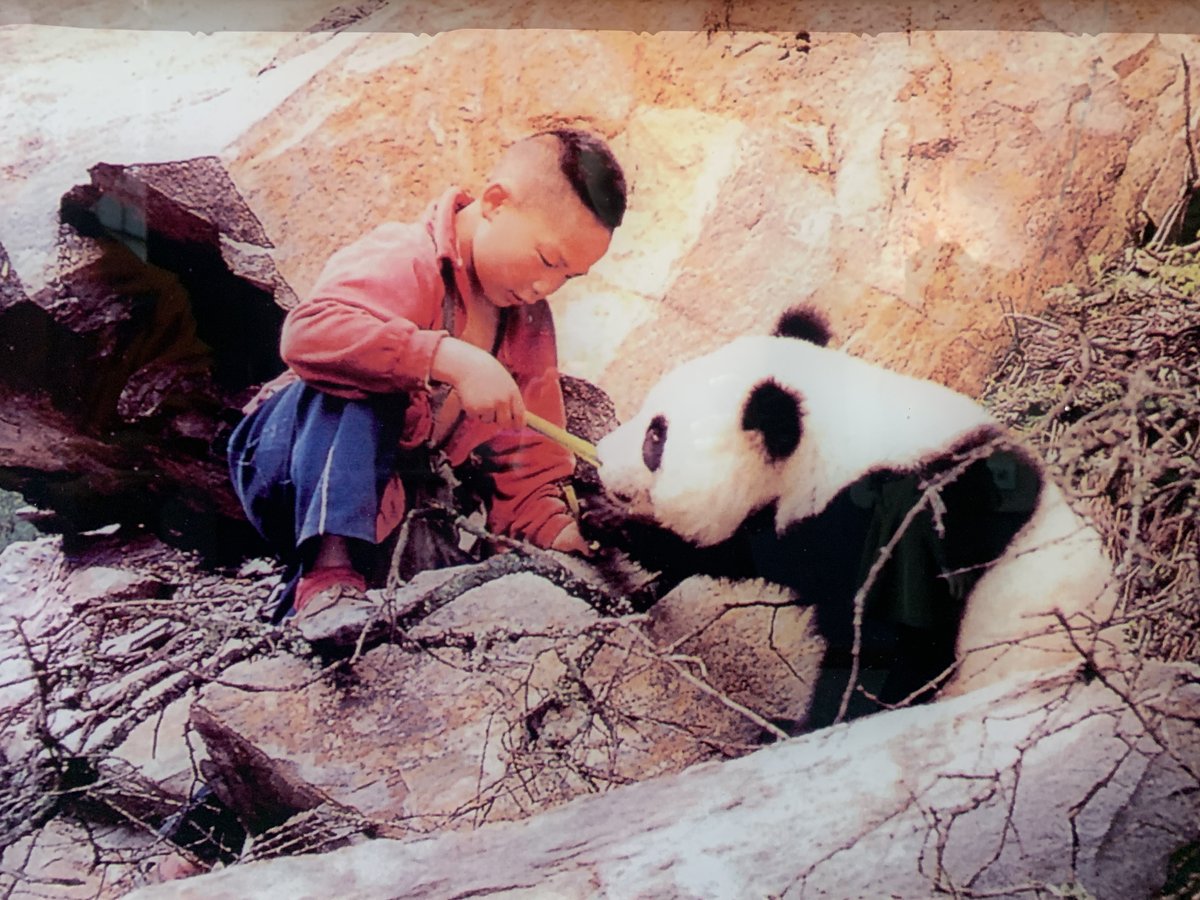

In a church in Baoxing county, built by a team of missionaries that included David, photos from the 1980s show local Tibetans playing with wild pandas and feeding milk to the cubs. Gao believes this is the ideal relationship for pandas and humans: if people stop hunting pandas and protect their habitat, local residents won’t have to move away from the territory.

Rather, conservation can bring benefits to local communities. Sichuan’s giant pandas helped generate 370 billion yuan from ecotourism in 2022, almost a quarter of the province’s GDP. Villages near reserves try to attract visitors by playing up their panda credentials with giant panda images and elements all over town. Baoxing received over 142,000 tourists during the Labor Day holiday from April 29 to May 3 this year.

For Luo Zhongchun, a 44-year-old guesthouse owner in “David New Village,” a merger of several villages near the panda reserves constructed in 2013 and named after the 19th century missionary, the panda boom raised her income and aided her village’s recovery from an earthquake in 2013. Luo was a farmer before that, but “after the earthquake [the authorities] rebuilt our house and constructed roads for us. Gradually our village became a tourism spot, so my family decided to run a guesthouse as many of my neighbors did.”

In 2014, the Baoxing county government and the China Foundation for Poverty Alleviation (CFPA), an organization affiliated with China’s State Council, launched a post-disaster reconstruction project to promote the panda-themed tourism industry, mainly by encouraging locals to set up guesthouses. They also built the Panda Culture Communication and Education Centre which now houses two giant pandas in captivitiy. By 2018 there were 42 guesthouses in David New Village, which received around 10,000 visitors during the three-day Labor Day holiday that year.

Finally, wild panda numbers may slowly increase again: The Ministry of Ecology and Environment announced in 2021 that they no longer considered the bear endangered in the wild, with the population exceeding 1,800. The IUCN reclassified giant pandas as “vulnerable” in 2016, an improvement on “endangered.”

That doesn’t mean pandas are likely to be seen roaming around Baoxing or elsewhere any time soon, though. Most of them are now living far away from humans. “It’s true that many Sichuanese may never see a giant panda, but that won’t stop us from protecting them,” says Gao. “Has anyone ever seen a dragon? No. But we never doubt the importance of the dragon to Chinese people. The same goes for giant pandas.”