Four translators and interpreters talk about the impact new technologies like generative AI are having on their work and future career prospects

Since ChatGPT burst onto the scene last year, stories have abounded about how AI will take the jobs of millions. In China’s creative industries, that process is already well underway. Generative AI models can, in a matter of clicks, produce intricate images, succinct copy, and even error-free code.

One industry that has operated under the shadow of technology since before ChatGPT was even conceived, however, is translation. Some thought Google and other translation software would be the end of human translators, but they survived. Now, the industry is changing again in the face of large language models. Here, four translation industry insiders working in English and Chinese describe how AI has changed their work.

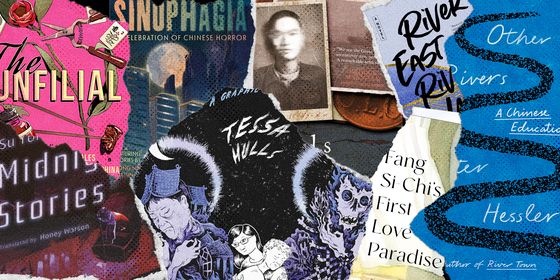

Dylan Levi King, translator of various Chinese authors including Jia Pingwa, and writer

As I started to establish myself as a translator, I had an image in my head of what their practice looked like: They sat in front of a word processor, with the original work cracked open beside them, and pounded out their interpretation. This is still how I usually work, but I’ve come to see I’m an anachronism.

When I met the Turkish translator Giray Fidan at an event in Beijing, he was taken aback that I did not employ computer-assisted translation tools. He pointed me in the direction of software that could maintain a personalized lexicon, plugging in automatically the translations of terms and phrases. If I wanted to go further, there were tools that incorporated machine translation more completely.

In fact, machines already do most translations. Translation agencies are more likely to engage polishers—people checking through machine translations—than translators.

Fewer are willing to admit their use of large language models than will talk about computer-assisted translation tools. This is down to a popular belief that large language models (LLMs, such as ChatGPT) possess an intelligence not claimed by other software. These translators are using the tools that they are told will replace them. That’s frightening to them.

They admit privately that ChatGPT is useful, however. They appreciate that instructions on tone and register and word choice can be prepended, and then modified along the way to produce a more appropriate translation.

The choice by translators to throw their lot in with the machines owes more to economic conditions than philosophical considerations. As pay rates went down in an age of global competition, very few translators could make a living without these tools. Augmenting outflow with machine translation was the only way to turn out the massive amounts of text required to keep afloat. The human translator got stupider while the machines got smarter. The replacement of most human translators with machine translation and LLMs has already happened.

My own practice is still anachronistic. This is partly a philosophical choice. It is deeply unfashionable, but I do believe that the promotion of LLMs and machine intelligence is helping to make us—individually and as a global society—stupider. But my choice is made easier by the fact that I am privileged to work mostly with literary fiction, whose translation rewards a degree of artistry that machines cannot yet be compelled to attempt.

I am working often with texts, like Jia Pingwa’s The Shaanxi Opera, which, because of their use of dialect phrases, classical allusions, and poetic language, are still unable to be fully parsed by most human readers, let alone LLMs.

I am lucky and I am cursed: The technology barons in charge of generative artificial intelligence development don’t give a damn about literary fiction, which means they’re just like most people in the world.

Wei Lingcha, translator, former director of the US office of the China Publishing Group

When I worked in the United States in 2018, I was asked to review a translated book about Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region. The phrase 塞上江南, a nickname for Yinchuan, capital of Ningxia, came up frequently. The phrase itself means that Yinchuan, a city north of the Great Wall, is so beautiful and cultured that it looks like one south of the Yangtze River—an area known as Jiangnan—where China’s most advanced cities have been for much of the last few hundred years. I looked it up on a translation app, and got a nonsensical answer: “plug in Jiangnan.”

Frankly, I have often been frustrated by translation technology. One of my friends works with a company that produces translation devices. On a visit to him at his company, he introduced me to one of their machines, which was quite cute and no larger than a human hand. I turned it on and gave it a go. Typing in the Chinese phrase 五大三粗 (an idiom meaning “sturdy and towering”), I asked the machine to render it into English. The result: “five big and three thick”—much to my amusement and somewhat to my friend’s embarrassment.

It dawned on me that the machine may work well with sentences on a scientific subject. I made it translate a second sentence: “水是由氢气和氧气组成的.” This time the machine worked perfectly: “Water is composed of hydrogen and oxygen.” My friend was relieved.

ChatGPT, however, represents a major breakthrough in AI. I’m confident it will become widely used by almost everyone in the foreseeable future. The reason: it’s based on texts and big data in the English language, sufficient and scientific enough to lead to pretty effective solutions. Amazingly, ChatGPT’s translation results match the original text in style. It can choose to be academic or colloquial as the need arises.

A domestic version of ChatGPT has recently been released. Again, I typed in 塞上江南 and asked for its English translation. The result: “the southern part of the Great Wall.” Much better. But it was still not faithful to the actual meaning.

I’m no technology geek, but I believe ChatGPT and its variants in China will be conducive to translators’ daily work in the future. But if you’re looking for creativity, forget it.

Ana Padilla Fornieles, translator of Chinese, English, and Spanish

Nowadays, AI is a trending topic and a looming menace for many professionals across different fields. Will this technology really mimic and surpass your skills, and then rob you of your job? The answer is not one-size-fits-all, but long before AI came to be, we professional translators were already facing our alleged impending doom with widely available multilingual machine translation services. Google Translate launched in 2006; fast forward to today and…we’re still here.

Machines never quite replaced us, though they did, and still do, provide plenty of hilarious gaffes. Case in point: the other day, just for fun, and as I approached penning this piece, I put the word 中国 (China) on a certain browser’s machine translation service and set it to translate into Spanish. Where I expected to get a straightforward, no-nonsense “China,” I got “porcelain.”

This is not to say that I don’t harbor my own fears and suspicions about AI and the future of our industry—quite the contrary. It’s also worth mentioning that I haven’t used AI at all, neither for personal nor professional use. In that way, I’m blissfully unaware of the threat that might be heading my way. However, I would hope that if these technologies are here to stay—and it certainly seems they are—we will be allowed to coexist with these new realities and make them work for us.

Nobody questions a surgeon’s use of their tools and medical equipment to mend a patient in the operating room. A plumber, understandably, won’t fix your pipes without their trusted toolbox, either. Translators, however…The general public regards us as walking dictionaries, including for highly specialized vocabulary. You’re a moment of hesitation away from people doubting your knowledge if you can’t name an obscure botanic term in each of your language pairs at their random request.

National public examinations to become a translator in Spain are still carried out yearly, banning the use of any tools, from dictionaries to even computers for typing. It’s just you, a sheet of paper, and a pen. Ironically, the anachronism of their ways is a reminder of the issues we often encounter in our daily professional lives.

A translator using a series of tools—yes, machine translation included—to either optimize their time and resources or perhaps start dissecting a complex sentence? Sacrilege!

Translators have all probably met the customer who turned down our services because they were “too expensive.” After all, the customer will argue, that their cousin who studied a language course could do the same job for a fraction of the price, or they can feed the assignment to whatever machine translation tool for free. Translators often experience having their tools used against them, to cheapen and undermine their training and skills, yet we aren’t supposed to use them to our benefit, as well as with our expertise.

I don’t necessarily fear AI and its iterations so much as the people (and corporations) wielding them. In the name of “productivity” (code for “money,” of course), they have typically shown little to no regard for the very work they aspire to streamline out of its wonderfully human complexity.

Shi Hang, former Chinese interpreter

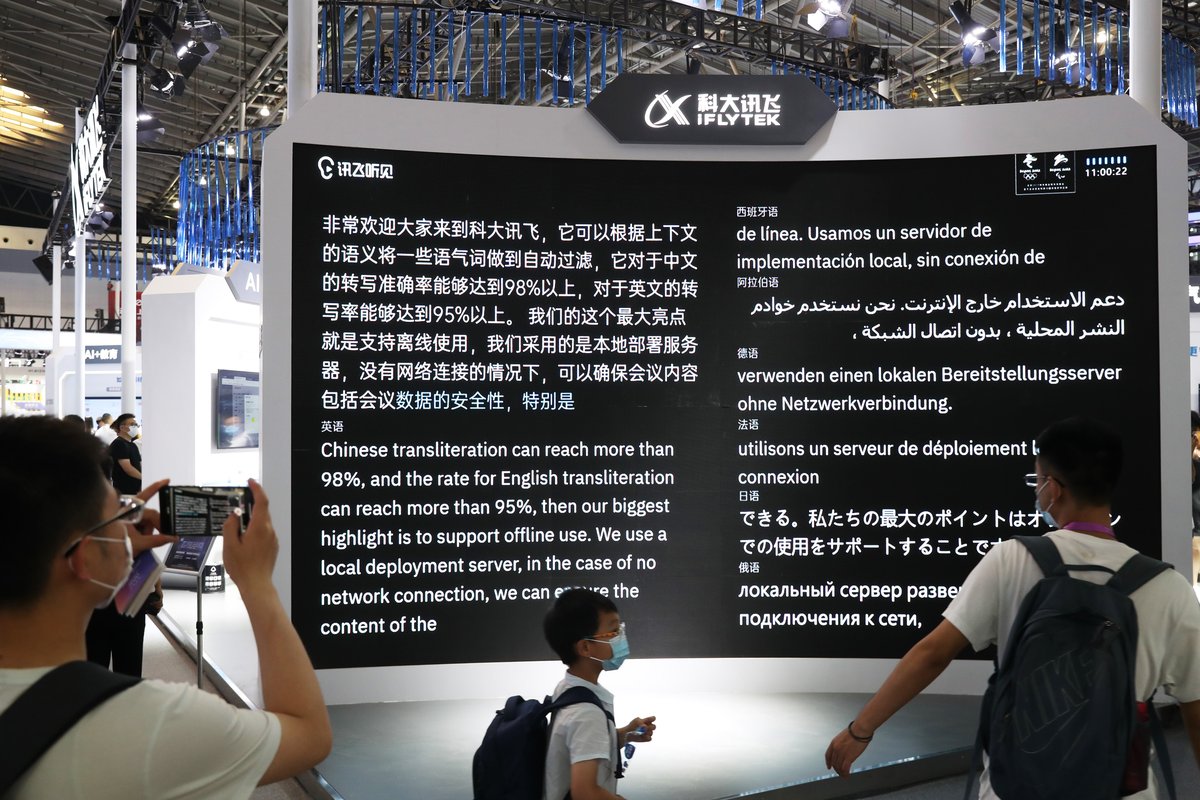

About seven years ago, I began to notice the AI trend when the tech company iFlytek launched its AI products. Despite the development of technology, I don’t believe interpreting, including simultaneous interpreting, can be fully replaced by AI. This is because interpreting involves the fundamental logic of human learning—we gradually gain knowledge through experience and feeling. For machines, however, it often means a simple analysis of information without any judgment on values.

Moreover, in the realm of diplomatic relations between two government leaders, trust in humans surpasses trust in machines. Whether it’s for conferences or negotiations, humans can analyze and interpret the nuances of communication. I place greater trust in human emotion and intuition. There is a natural ethical trust between humans, as machines lack conscience.

If we contemplate using AI for translation, we must be prepared to invest a significant amount of money in training the AI with vast amounts of text. When comparing the cost of training AI to the expense of hiring a person for the job, which do you believe is higher?

Although I’m no longer part of the industry, I do believe that in some contexts, AI can assist translators. At high-end conferences, interpreters can consult LLMs like ChatGPT for background knowledge as part of their preparation. Recently I’ve also switched from my search engine to ChatGPT.

Occasionally, when I need to perform a translation, I use an AI tool to translate the text and then proofread it myself. This method has certainly streamlined my workflow and enhanced my efficiency.

I recognize that my former interpreter colleagues might disagree with me doing this, but it’s the reality we face, and we must confront it. During my studies at École Supérieure d’Interprètes et de Traducteurs in France, one of my instructors often remarked that the only constant in this world is change. Thus, as everything evolves, we need to embrace these shifts.

Having contributed to training courses for translation and related studies, I’m convinced that while AI aids translation, one still needs to actively learn languages. Solely relying on machines when abroad is not prudent.

However, given the proliferation of AI products, it raises the question: Will students continue to be drawn to study translation?

Editor’s note: Ana Padilla Fornieles, Dylan Levi-King, and Wei Lingcha are all regular TWOC translators and contributors

Will ChatGPT Really Kill the Chinese Translation Industry? is a story from our issue, “Online Odyssey.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.