Livestreaming has boosted book sales in China via its massive online traffic, but does it translate into real gains for publishers, or just a short-term ploy to cash in?

There’s a popular saying in China: Knowledge can change one’s destiny. Now, a livestream can do the same for a book.

This became especially apparent in early 2024, when one of the country’s top livestreamers, Dong Yuhui, invited Abdulrazak Gurnah, the 2021 Nobel Prize in Literature laureate, to join him on his Douyin (China’s version of TikTok) channel. During their 100-minute conversation, more than 110,000 copies of Gurnah’s first Chinese-translated series, priced at 218 yuan each, were sold.

Around the same time, the Chinese literary magazine People’s Literature (《人民文学》) sold over 990,000 copies during a four-hour livestream, also hosted by Dong. Sales kept climbing even after the stream ended, eventually surpassing 1.2 million copies.

Yet neither of these can hold a flame to Chi Zijian’s The Last Quarter of the Moon (《额尔古纳河右岸》), another beneficiary of Dong’s channel. Since his recommendation, the novel has been printed in over six million copies—up from just 600,000 before Dong’s endorsement, according to the author.

Such sales figures have caused a seismic shock within both the literary world and the publishing industry. And while more publishers are embracing livestreaming to boost sales, it does not always ensure increased profits. Instead, the pivot seems to reflect a complex, and at times begrudging, struggle within the industry to respond to modern content consumption trends.

Read more about livestreams in China:

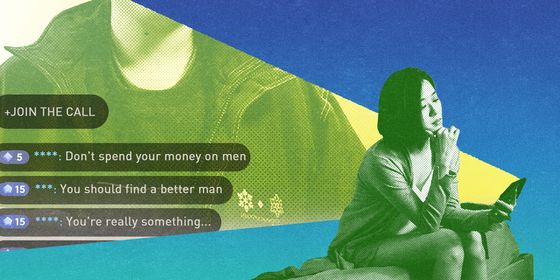

- Can Livestreaming Be the New Way to Solve Relationship Issues in China?

- The Boom of College Admissions Counseling in China

- DeepSeek Sells: How AI is Revolutionizing China’s E-commerce Landscape

In today’s China, book-related livestreams—either through partnerships with influencers or self-run channels—have become a mainstream marketing model. Authors provide professional content and works, while streamers play on viewers’ emotions to drive purchasing desire—together, they work to shift copies.

With their strong selling power and large fan bases, livestreamers can explain content in vivid, relatable language and stimulate audience engagement through real-time interaction.

“When I buy books through short video platforms or livestreams, a really strong recommendation from the host can give me an instant rush that makes me place an order right away. But when I shop on [online book retailer] Dangdang or [e-commerce platform] Taobao, I usually take time to read the synopsis and reviews carefully, sometimes even leaving the book in my cart for a while. It’s a much less impulsive process by comparison,” Chen Sasa, mother of a 7-year-old and a frequent book buyer for both herself and her daughter, tells TWOC.

Zhou Ran, a book marketing manager at a major Chinese publishing house, adds that livestreaming is also a powerful tool for gauging consumer preferences. “Since livestream hosts interact directly with readers, feedback is instant, and the relationship is more personal than that between readers and publishers—making [livestreaming] a more effective way to understand readers,” she tells TWOC.

This close bond between influencers and their audiences not only boosts the market value of featured books and publishing houses, but also rekindles viewers’ interest in literature and inspires a desire to read. In the comment section of Dong’s book recommendation videos, endless followers shared their feedback and sincere appreciation of the works he highlights.

“Because of Yuhui, I’ve read three paperback books, and I’m now planning to get The Temple of Earth and I. You have to understand—I’m a housewife with only a middle school education, and I haven’t touched a printed book in years,” reads one comment.

In April of this year, Dong even received a special “Communication Contribution Award” at the prestigious People’s Literature Award. As the citation noted, he has “repeatedly brought literature to readers, awakening the deep-seated yearning for books in countless lovers of literature.” Though it’s worth noting that Dong had helped People’s Literature magazine—also the award’s organizer—sell millions of copies.

Livestreamers like Dong have not only helped readers, but also breathed new life into struggling publishers. A Beijing-based children’s book editor surnamed Wu tells TWOC that her company launched their own channel after the pandemic and tried going live twice a week. However, building a following proved to be tougher than expected, and the stream results were underwhelming. Turning to well-established influencers saved the company from going under. “Now, we mainly rely on influencers to recommend books,” Wu says.

But impressive sales figures and cultural buzz don’t necessarily translate into good news for all publishers. Zhou’s company jumped on the livestreaming bandwagon, but pulled out soon after the costs of maintaining the channel became unsustainable.

“People might find it perfectly reasonable to spend 20 yuan on a cup of milk tea,” Zhou observes, “but hesitate to pay the same amount for a book—partly because the market is flooded with clearance sales offering books for 9.9 yuan, often with dubious copyright status.”

Multiple news outlets and media think tank studies have revealed that low prices on e-commerce platforms can lead search algorithms to favor pirated books, boosting their exposure and profitability. As a result, pirated editions often crowd out legitimate versions—a classic case of “bad money driving out good.” Still, for consumers like Chen, who has bought books through all mediums, pricing remains the most influential factor in whether she makes a purchase.

The livestream boom has further prompted e-commerce platforms to put more pressure on publishers to lower prices to attract consumers. This friction came to a head in May 2024, in the lead-up to JD.com’s annual mid-year “618” shopping festival. At the time, the e-commerce giant pushed publishers to sell their books at 20 to 30 percent of their original price, prompting 10 prominent Beijing publishers, including Tsinghua University Press and Peking University Press, to issue a joint statement refusing to participate in their deep-discount scheme.

“For many publishers—like ours—the costs, including royalties, are quite high,” Zhou explains. “When platforms keep driving down prices and raising commission fees, there’s barely any profit left for us.”

Although JD.com finally adjusted its promotion strategy, allowing publishers more autonomy in deciding which books to discount and by how much, the tension arising from what constitutes fair pricing for publishers and the competitive pressures of e-commerce platforms remains.

Meanwhile, this pricing war also has a direct impact upstream, influencing the number and type of new books publishers are willing to invest in. Qin Yin, an editor at a top publishing house in Beijing, told Economic Observer Network in May last year that the high upfront costs of publishing new works must be recouped through sales. This is especially true for some imported books, where publishers must also pay copyright royalties. In addition, licensing agreements typically only last three to five years, creating a tight timeline for many publishers. If the book underperforms—selling less than 3,000 to 5,000 copies during the term—the publisher is almost guaranteed to lose money, according to Qin. The result is that many publishers are turning to lower-cost alternatives, such as public domain works or reprints of previously successful books.

Behind these struggles lie a more concerning fact: China’s book market, despite its pivot to influencer-led sales, has been stagnant. In 2020, China’s book retail market experienced its first decline since 2001. According to OpenBook, a Beijing-based publishing industry research provider, the overall book retail sales further declined by 1.52 percent year on year in 2024. Physical stores, major e-commerce platforms, and vertical sellers all reported losses. Even the profitability of content-driven commerce (formerly short-video commerce), which was once at the helm of online sales, has decreased significantly.

Yang Wenxuan, the managing editor of publisher Huawen Tianxia Book, equated the health of the publishing industry to the nurturing of a tree during an interview with China Publishing Today last December. “Neither influencers nor group-buying communities want to promote new titles...they’re all ‘harvesting the crops’ rather than ‘planting seeds.’ With the cost of online traffic so high now, planting a tree is genuinely hard,” Yang said, “Each livestream session often requires hundreds of thousands, even millions, in investment.”

He added that, “While some publishing houses are seeing outsize growth, it’s merely a redistribution of market share. The overall ‘pie’ of the book market is shrinking and being re-divided. One company’s gain comes at the expense of another’s decline—or even demise.”

With the rise of e-books, reading apps, audiobooks, and short video platforms, all competing for readers’ eyeballs, printed books are no longer the primary medium for acquiring information or entertainment as they once were.

The latest China National Reading Survey, released in April this year, shows that the digital reading exposure rate in China exceeded 80 percent for the first time in 2024. Among those digital reading devices, reading on mobile phones accounts for as much as 78.7 percent. Meanwhile, the country’s overall digital reading revenue was 66 billion yuan, with the user base reaching 670 million. With paid downloads and subscription models, e-books are often more competitively priced than print editions, and platforms frequently run promotions to further lower costs.

In this rapidly changing digital sphere, the ways books are being consumed will be constantly changing. Whether the livestreamed book sales boom will remain is yet to be seen. Zhou’s company has decided to give livestreaming another shot amid shrinking sales—this time experimenting with personal accounts instead of the official corporate channel to potentially lower costs.

Dong, the top streamer in the book field, on the other hand, sells more consumer goods than books nowadays. During a recent livestream, featured products included his best-selling item, The Last Quarter of the Moon, swiftly followed by thick-cut milk toast, anti-dandruff shampoo for teenagers, and summer slippers.

Chen last ordered books from a livestream in April 2024—a five-volume series from Peking University Press via a WeChat channel. To this day, they remain uncracked.

How Livestreams Became China’s Newest Tool for Selling Books is a story from our issue, “Smart Nation.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.