With PhD graduates outpacing available positions, young Chinese scholars face an uphill battle for jobs, resources, and recognition in an increasingly crowded academic arena

Nearly two months after earning her PhD, 29-year-old Anja Ren is still unemployed. Since March, the start of the job-hunting season, she has sent out more than 18 applications for faculty positions at different colleges—yet only three have replied. “Landing a job these days is hard,” she admits.

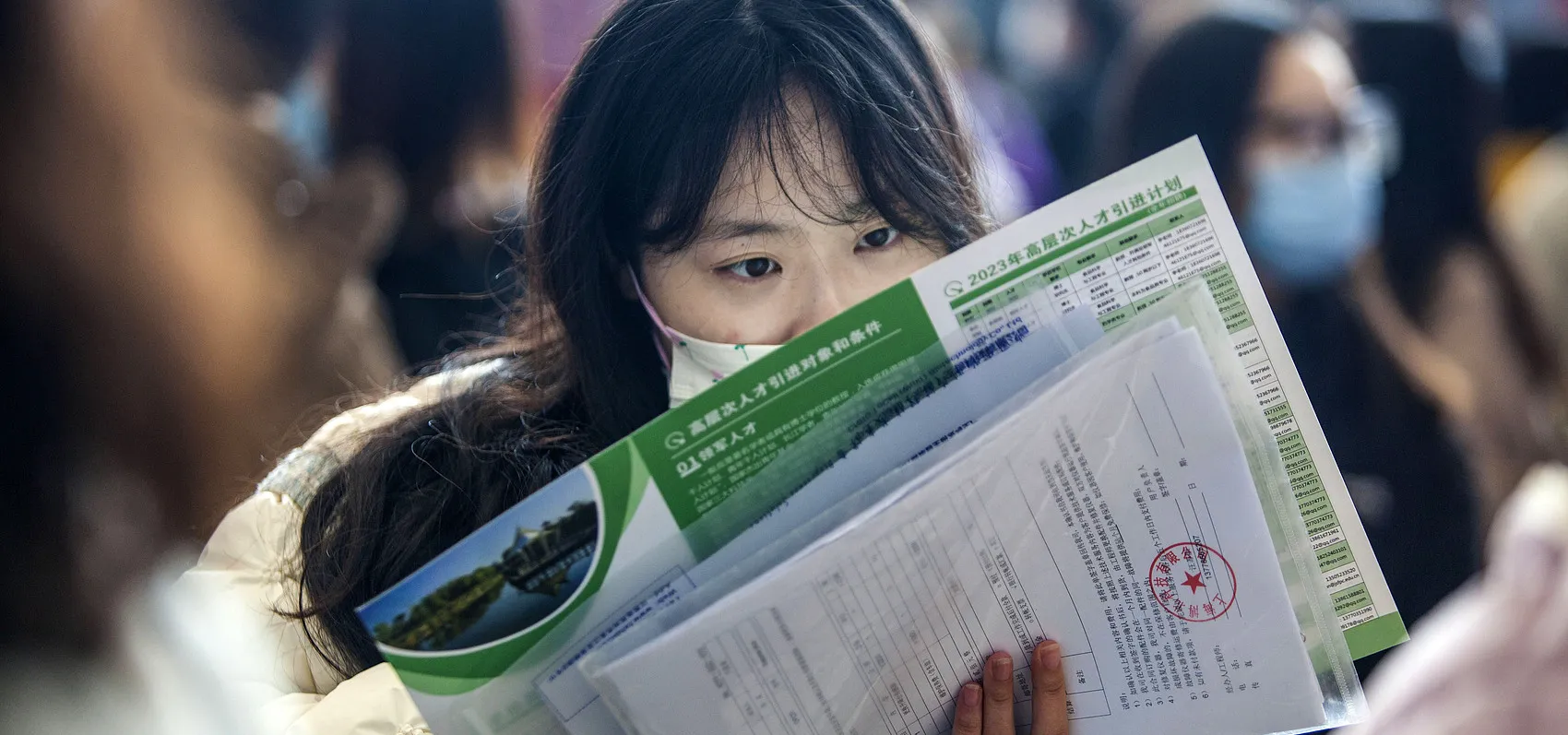

For China’s newly minted scholars, getting—and keeping—a job has become an unforgiving race. In 2024 alone, over 97,000 students in the country graduated with PhDs, almost double the number from a decade ago. Yet the number of positions at universities and research institutes has grown only marginally in the same period. As a result, the competition for academic jobs is fiercer than ever.

An employment winter

“I became determined to pursue a PhD after realizing my potential during my master’s program,” Ren says. But she never expected that finding a job after graduation would become such an anxiety-inducing challenge.

For job-seekers in China, 2025 has been one of the toughest years yet. As enterprises cut back on hiring, many undergraduates and master’s students are opting to pursue a PhD, hoping that a higher degree will give them a competitive edge in the job market.

Read more about higher education and careers in China:

- The Woes of China’s Liberal Arts Students

- Meet the Chinese College Grads Who Took Up Blue-Collar Jobs

- How a Fiercely Competitive Job Market is Forcing Graduates to Change Their Plans

Yet many quickly realize that earning the degree is less an escape and more a leap from one intensely competitive race into another. A survey published by Nature magazine in June 2025 points out, doctoral graduates vastly outnumber the available jobs in academia worldwide, with competition especially fierce in China and India.

According to recruitment website Zhilian, only 44 percent of Chinese graduates with postgraduate degrees received job offers in 2024, a 12.3 percent drop from the previous year. Even undergraduate degree-holders had a slightly higher offer rate, at 45.4 percent. The highly specialized training that doctoral students receive means there are few positions corresponding to their skills outside of academia, resulting in low employment rates. Even those who land a job often find out that the work does not require such a high level of qualification.

As competition heats up, universities are setting ever-higher bars for applicants, expecting PhD graduates to have published in leading journals or to have led significant research projects. Emma Huang, a 31-year-old PhD graduate in literature, knows the pressures all too well. Despite earning her degree from one of China’s top universities, she admits she is still lagging in the job market. “So far, I’ve only published one paper in a C-level journal—hardly enough to compete for faculty positions at top universities,” Huang tells TWOC. “To have a real chance, the only option left is a postdoctoral program, which would add more uncertainty to my future job search.”

The pressure to publish does not end after scholars enter the academic workforce. Over the past few years, top Chinese universities like Tsinghua University have implemented a “publish or perish” system for young academics. Those who fail to publish enough papers to secure an associate professorship within a prescribed time frame face dismissal.

These cutthroat trends are also trickling down from top-tier institutions. When Ren reached out to one of her former professors at the second-tier university where she got her undergraduate degree, she was surprised to find that even at such a little-known institution, holding onto a job was harder than before. “According to my professors, all new faculty are required to accumulate research scores based on the number of papers and research projects they have produced,” Ren explains. Her university introduced the rating system around 2021, hardly a unique one in China, and in the years since, the burden of endless evaluations has grown heavier.

Climbing the academic pyramid

For many PhD graduates, securing a coveted lecturer position is only the first step on a very high ladder.

The Chinese university system classifies academics into three main ranks: teaching assistant (typically a first-year hire) and lecturer at the bottom, associate professor in the middle, and full professor at the top. Promotion to a higher rank requires years of teaching and research, with strict benchmarks for evaluation such as publications in high-impact journals or significant project leadership.

There are also a parallel hierarchy of so-called “talent titles,” including the Distinguished Young Scholars Fund, the Changjiang Scholars Program, the Ten Thousand Talents Plan, and high-level recruitment schemes for overseas returnees.

These programs were originally intended to reward outstanding research and attract overseas-trained scholars back to China. Over time, however, talent titles have become means to gain resources and influence within academia. Gaining a talent title could mean easier access to grants and laboratories, or even fast-tracked promotions. As a result, many young scholars without a talent title feel locked out of opportunities, no matter how solid their research may be.

Driven by the relentless pursuit of prestigious titles, many university scholars find themselves sacrificing rest and personal time. “For a period of time during my PhD, I started having insomnia as my research outcomes couldn’t meet my supervisor’s expectations. This basically lasted for two years.” Ren tells TWOC.

Another consequence of the system is the rise of academic misconduct. With the number of publications directly tied to employment and promotion, academic fraud has become widespread. “To land a postdoc in Beijing, you’re expected—though it’s never stated outright—to have three C-level journal papers from your PhD,” Huang explains. For many young scholars, these demanding quotas are simply out of reach, fueling a shadow industry of ghostwriting and pay-to-publish journals.

Beyond research and publishing, Chinese PhD students often have to handle a variety of administrative and non-research tasks. Supervisors, often acting as project managers, assign students a variety of administrative tasks, even personal businesses. This is partly due to the traditional hierarchical culture in academia, where PhD students need endorsements from senior scholars to publish papers and accumulate achievements.

Some extreme cases of exploitation have ended in tragedy. In 2018, Yang Baode, a 28-year-old pharmacy student at Xi’an Jiaotong University, took his own life after long-term exploitation by his PhD supervisor. Among other abuses of power, she had asked him to clean her house and wash her car, and refused to let him study abroad.

To stay or leave?

As the number of PhD graduates in China continues to grow, the difficulty of finding academic positions has driven some to seek alternative paths.

The most common approach is to accept a position at lower-ranked institutions in developing regions and provinces. These universities have lower barriers for recruitment and offer faster promotion tracks and lighter teaching loads. Ren, who published only one paper in a minor journal during her PhD, focused on second-tier colleges in smaller cities from the outset, knowing she had little chance of landing a position at a top university. “I thought the application would be easier, and at second-tier colleges, you can somewhat escape the ‘publish or perish’ pressure,” says Ren.

However, lower-ranked institutions pay lower salaries, and scholars find themselves lacking in funding, equipment, and meaningful projects, making it harder to achieve promotions. “Choosing a position in a remote region often means half-abandoning your research career,” Huang claims. “There are limited opportunities for academic exchange, which makes it hard to build networks, and the chances of moving on to a more prestigious institution later are slim.”

Other PhD graduates venture into the broader job market. Some municipal governments and private sectors have launched incentive programs to attract high-level researchers and support regional development. For example, the government of Taiyuan, Shanxi province, offers PhD holders a talent subsidy of up to 530,000 yuan. Top-tier scientific talent may also receive a one-time housing allowance of 1 million yuan.

While these offers are attractive, some students find it hard to accept stepping away from academia after investing years into getting a doctorate, and may face stigma for doing so. “To be honest, a lecturer’s title doesn’t only look good on your CV. It can boost your appeal on the dating scene, too,” Pan Ying, a 33-year-old PhD student in biological sciences, tells TWOC. “It also means long summer and winter breaks.”

Pan had worked in the private sector for four years after getting her master’s degree. Having always dreamed of getting a PhD, she applied to a doctoral program in the UK but realized academia wasn’t the right environment for her as soon as she began her research.

Yet PhD training is almost entirely geared toward producing academic researchers. “The focus of most doctoral research is often highly theoretical and not very practical,” she explains. “If I hadn’t had four years of work experience before starting my PhD, I might have faced difficulty finding work after graduation as well.”

Currently, some Chinese universities are taking steps to help PhD graduates transition more successfully into the job market. For example, institutions like Shanghai Jiaotong University have introduced professional-oriented doctoral programs, distinct from traditional research PhDs. By assigning industry mentors and tailoring projects to practical applications, these programs aim to better equip students for careers beyond academia. Additionally, a number of PhD graduates are also opting to take the civil service exam.

As the value of a PhD in the job market diminishes, some have chosen to give up pursuing a PhD, while others argue that a doctoral degree is about more than just career prospects. “In China, there has long been a cultural reverence for academic degrees. During my postdoctoral studies, that dream lost some of its luster, but it didn’t make those four years any less valuable,” says Pan. She believes that pursuing a doctorate honed her ability to think logically and systematically, cultivating a disciplined perspective for understanding the world.

“Another unique quality of a PhD is the courage to push your own boundaries and see how far you can go,” Huang explains. “Now I know that even in an unfamiliar field, I can still succeed. That’s what makes the experience so compelling.”

Additional reporting by Lin Zhilu

Some names in the story have been changed to protect the interviewees’ privacy.