Yue opera, originated in Zhejiang and known for its gender-bending roles and progressive stage design, is building a feminist dreamscape for a new generation

F For Micky Wang, a 26-year-old Columbia University graduate with a connoisseur’s love for traditional arts, a trip home to China is a pilgrimage to indulge his passion: Yue opera, a 120-year-old, female-dominated theater genre popular in the Zhejiang, Jiangsu, and Shanghai regions. His first stop was the Nanjing Yue Opera Museum in Jiangsu’s provincial capital. There, he lingered with reverence before costumes once worn by legendary masters, before heading to the museum’s trendy café to order a milk tea inspired by Yue opera—prepared by a Yue opera singer as part of the museum’s strategy to engage the audience. With a drink in hand, he stepped into the courtyard and sat against the backdrop of the Qinhuai River to enjoy the timeless melodies of a live mini-performance by the Nanjing Yue Opera Troupe, just a few steps away.

Days later, on October 18, in his hometown of Beijing, Wang’s journey culminated in a trip to Peking University, where the troupe staged its new production The Weaver (《织造府》), a time-travel reimagining of Cao Xueqin’s (曹雪芹) Qing-dynasty classic Dream of the Red Chamber (《红楼梦》). Captivated, Wang savored the show, with the line from the protagonist Jia Baoyu, “only one sight and fall for one life,” echoing in his mind. As the curtain fell, his rapture was broken not by the din of the audience leaving but by the buzz of a nearby fan meeting in the foyer just outside the performance hall—a chance for a technical deep-dive with cast members and heartfelt praise for the troupe’s newest talents, many his junior. Wang later chewed over the details of his recent experiences: what he had witnessed wasn’t just entertainment; it was a century-old art form being reimagined for people his age, vibrant and in motion.

Read more about China’s traditional culture today:

- A Tiny Rural Community’s Grand Effort to Welcome the Ancestral God | Photo Story

- China’s Rare Woods: Bearers of Beauty, Toil, and the Supernatural

- Scent Across Time: How Traditional Fragrances Quiet the Clamor of Modern Life

Reimagining tradition

The phrase “一见钟情,” or “love at first sight,” often evoked the romantic tragedy of Jia Baoyu and Lin Daiyu in Dream of the Red Chamber. Their bond is rooted in myth: Lin, the mortal incarnation of the Fairy Plant, is fated to repay her cousin, once the Divine Attendant who watered the magic plant, with a lifetime of tears. Yet even this preordained love, set in a society where cousin marriage was customary, ultimately succumbs to the cruel machinery of arranged matrimony.

Now, the Nanjing Yue Opera Troupe is reimagining this century-old tale, boldly challenging traditional expectations of women as passive and obedient—a reinvention that fits naturally in a genre traditionally dominated by female performers. In The Weaver, the last in a trilogy of works the troupe has created, Cao, author of Red Chamber, steps into his own novel, reincarnated as Jia Baoyu. The opera takes its Chinese name, literally the “Imperial Silk Manufacturing Bureau,” from Cao’s birthplace, the Jiangning Imperial Silk Manufacturing Bureau, a facility run by his family that once supplied textiles to the Qing court. As the semi-autobiographical protagonist, Cao becomes haunted by the characters he has created—especially the women—engaging in witty conversations and soul-searching debates with them regarding the defining moments of their fate.

“We wanted to explore the inner lives of these women through a contemporary lens; as Yue opera steps into the new generation, the narratives should also keep up with the ideas and lifestyle of the young audience,” explains Li, who plays both Cao and Jia. “A time-travel structure allowed us to ask: If Cao Xueqin could travel into the world of his own novel, how would he have acted?”

Through this new portrayal, Xue Baochai—Jia’s other cousin and, in some readers’ interpretations, the often-reduced “feudal lady” in the tragic love triangle—comes to recognize her own yearning for freedom. She leaves the Grand View Garden, inhabited by the family’s unmarried women and Jia Baoyu, a symbol of rigid tradition. Meanwhile, Lin’s death is reframed not as the pure heartbreak of learning that Jia will marry another, as depicted in Qing scholar Gao E’s continuation of the novel, but as a conscious release after having fully experienced love. These deeply modern acts of self-liberation depart from the traditional romantic themes that have long dominated Yue opera classics, resonating particularly strongly with younger audiences.

“I’ve always loved Baochai, but many people misunderstand her, thinking she’s scheming or calculating,” says Xiao Siyu, a freshman law student at Peking University who watched the show on campus in October. “But in The Weaver, I’m happy to see her struggle as a woman. I feel the portrayal of Baochai’s inner world is exceptionally insightful.”

Though not everyone is pleased with this new take on Red Chamber. On the review platform Douban, where the show holds a modest 7 out of 10, reactions are divided. While most praised the performers, as well as the intricate staging and lighting, some viewers questioned the logic of Cao reincarnating as Jia Baoyu, while others felt the characterization strayed too far from the original novel. However, such criticism is hardly new: nearly all Red Chamber continuations and adaptations over the centuries have drawn debate, given that only the first 80 chapters of the novel survived and the plot remains unfinished.

The production team tells TWOC that they welcome different interpretations, noting that The Weaver offers just one possible take. Classics endure because they can be revisited and reinterpreted across different times, audiences, and perspectives. Li isn’t too bothered by the criticism either, choosing instead to focus on refining her craft. Wang, the longtime Yue opera fan, feels the same: as long as the singing is good, he’s satisfied.

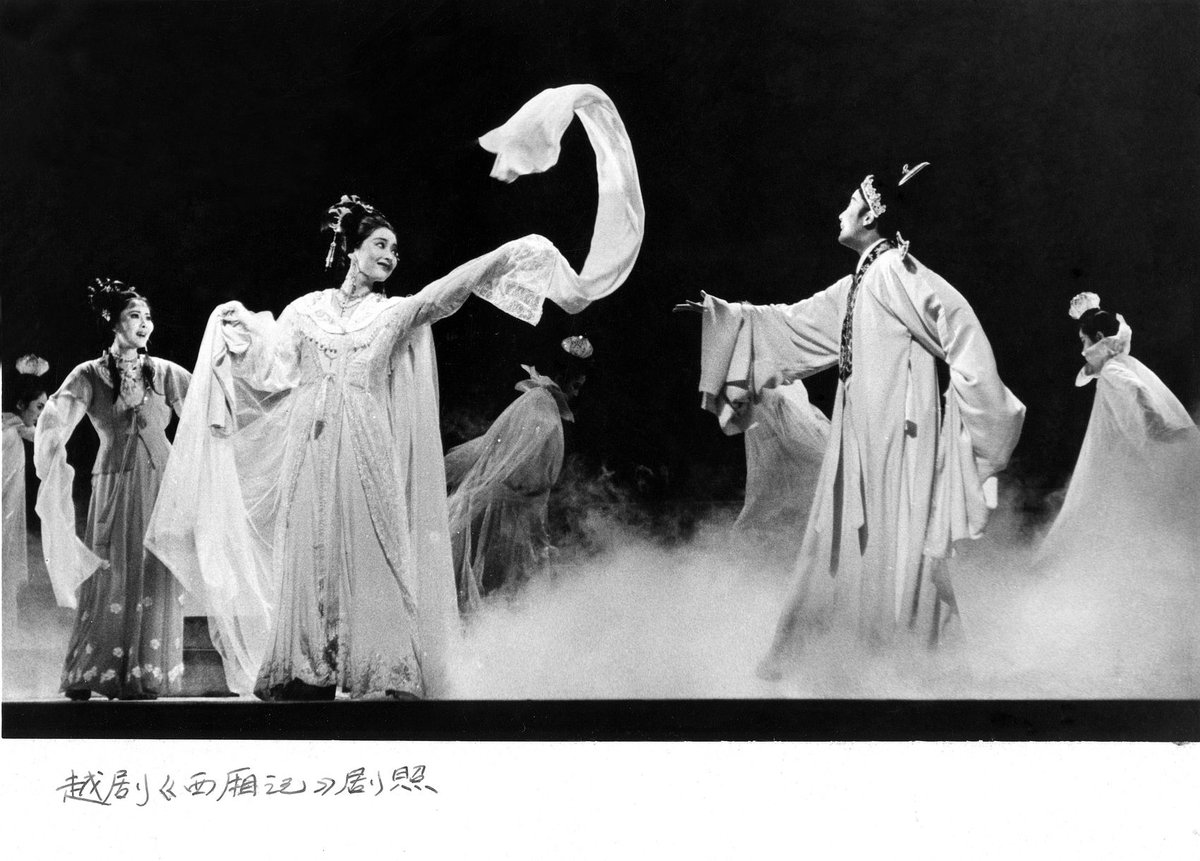

A feminine heart

Originating in Zhejiang’s Shengzhou in the early 20th century, Yue opera mostly focuses on traditional love dramas and “scholar and beauty” storylines, such as Butterfly Lovers (《梁祝》) and Romance of the Western Chamber (《西厢记》). Freed from the restrictions that once barred women from the stage during the Qing dynasty (1616 – 1911) and riding the boom of the entertainment industry in Shanghai and Tianjin’s foreign concession areas, Yue opera gradually evolved from a village pastime into an all-female tradition, gaining professional prestige. This, in turn, won the favor of an increasingly conscious and vocal female audience and their growing pursuit of agency in affairs related to love, counter to arranged marriages still prevalent at the time.

The feminist edge continues to thrive as audiences and actresses explore themes of personal growth, self-liberation, and modernity, pushing narrative and aesthetic boundaries of contemporary Yue opera.

In 2023, the Yue opera production of New Dragon Gate Inn (《新龙门客栈》), adapted from the eponymous 1992 wuxia film by the Zhejiang Xiaobaihua Yue Opera Troupe, became an overnight sensation with its pay-per-view livestream on Douyin, priced at just 9.9 yuan. A clip of the curtain call, featuring a one-armed spin between the lead actresses with a tender, transfixing gaze, went viral, introducing the classic tale to a new generation and expanding Yue opera’s audience. A Douyin livestream of the troupe on August 6 garnered over 9.25 million views, with nearly 4,000 viewers leaving more than 14,000 comments in real-time.

Xiao, the Peking University student, was also captivated by the online buzz two years ago while still in high school. The actress’s elegant and vibrant reinterpretation of the male character left a lasting impression on her, so when she learned that the Nanjing Troupe would be performing at her university, she signed up without hesitation.

Seeing a live Yue opera performance only deepened her fascination with the art form. She joined Peking University’s Yue opera society the same week after seeing The Weaver. At the orientation, she began learning about the rich history and cultural significance of the art form’s most distinctive convention: the nü xiaosheng (女小生), or “female scholar” role.

This tradition, in which actresses play charming male leads, lies at the heart of Yue opera’s unique connection with its audience, reframing classic romantic narratives, often penned by male scholars in feudal China, through a distinctly female lens. While celebrating ideals of love and freedom, many of these tales depict male actions, such as persistently following their love interests, that, by today’s standards, would be considered harassment.

According to Chen Tian, a professor at the School of Drama, Film, and Television Studies of Nanjing University, the nü xiaosheng role resolves this problem: “Visually, the nü xiaosheng role appears more delicate and slender, carrying a youthful, boyish charm. Psychologically, the tension between same-gender performers creates a safe emotional distance between the male and female roles...In Yue opera, the nü xiaosheng represents the idealized male figure in the minds of female audiences, stripped of masculine coarseness while retaining a gentle, feminine grace.”

Li Xiaoxu, who played Jia Baoyu in The Weaver, describes her male character’s gaze as “gentle, full of feeling, and devoid of aggression.” Growing up in a family that cherished the art form, Li immersed herself in Yue opera from a young age. Her professional journey began at the Jiangsu Provincial Drama School, where she auditioned for the role of Jia Baoyu—a character she found deeply compelling.

Her rigorous training to master the “Four Skills and Five Methods”—singing, recitation, acting, and combat, along with precise techniques relating to the use of hands, eyes, body, rhythm, and footwork during performances—has allowed her to transcend imitation and embody a refined, artistic version of masculinity.

In 2019’s Wuyi Alley (《乌衣巷》), the first installment of the Nanjing Troupe’s “Jinling Trilogy,” the story follows the layered love affair between noblewoman Xi Daomao (郗道茂) and the two sons of the famed calligrapher Wang Xizhi (王羲之). Li plays both male leads, transitioning seamlessly between characters with distinct vocal styles and textures. In Phoenix Terrace (《凤凰台》), the trilogy’s second work, she portrayed the poet Li Bai (李白)—a role that earned her both the 30th China Drama Plum Blossom Award and the Shanghai Magnolia Award, China’s highest theatrical honors.

A new stage

Li believes Yue opera’s relatively short history compared to other traditional Chinese opera forms is an advantage. Without the weight of centuries-old conventions, it has freely absorbed influences from Shaoxing opera, Peking opera, and spoken drama. Her own specialty, the Bi School, founded by artist Bi Chunfang and popularized in the 1950s, is known for its bright, robust vocals and comedic flair.

What makes contemporary Yue opera particularly compelling is also the immersive experience it provides. Environmental elements—compact layouts, integrated lighting, and enveloping soundscapes—increasingly adopted in recent productions, transform the stage, which sometimes extends into the audience area, into a dynamic space that dissolves the traditional boundaries between performer and spectator.

Unlike many other traditional opera forms that are slowly losing ground due to aging performers and audiences, Yue troupes in Hangzhou, Wenzhou, and Nanjing have increasingly promoted young actresses to leading roles. These performers—many born after 2005—infuse their roles with fresh interpretations while innovating new forms of fan engagement.

Unlike the polished distance in commercial idol culture, Yue opera fosters genuine closeness. Post-show conversations with the artists often blend technical discussion with personal encouragement. “The relationship between us is more equal,” Wang observes. “Fans don’t feel belittled.”

When Xiao attended the fan meeting at Peking University, she found the performers’ youthful faces nearly indistinguishable from her classmates’. “They look so young, yet deliver such mature artistry on stage,” she observes. “Exchanging thoughts with them about the roles and the shared challenges in our lives as young women makes me reflect more deeply...It’s encouraging to know that our generation has a voice within the troupe—that they can speak to our tastes and needs in new productions.”

Wang, who jokingly calls himself a “rare specimen” in the largely female fanbase, also feels that this women-centered culture offers a model for how men can show respect and understanding in their relationships with women.

Even fan practices like “shipping”—the act of supporting or imagining a romantic relationship between two characters—are viewed not as a modern distraction but as a continuation of tradition. “The idea of shipping has been around since the early days of Yue opera. Back then, we simply called it a ‘golden duo (黄金搭档),’” Li, the head of the Nanjing Troupe, explains. “I actually see it as an affirmation of the leads’ rapport and chemistry.”

Troupes nurture this bond with the audience through immersive events, such as a 68-yuan package featuring a mini-show and a drink prepared by cast members, transforming Yue opera from a museum piece into a living part of youth culture, where stardom meets fandom. Many of these actresses also run their own social media accounts to engage directly with their fans.

Inspired by these experiences, Xiao has signed up for a Yue opera performance class through her student society this semester. She hopes to experience the enduring appeal of this feminine art form firsthand and, schedule permitting, attend more performances. For her, it’s a cultural tonic—a refreshing companion to her unfolding academic life as a young woman.

The All-Female Opera Reimagining Freedom, Love, and Fantasy is a story from our issue, “New Markets, Young Makers.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.