Forget about Princess Di—the Qing court was rife with rumors that rival any modern royal scandal, from identity-swapped emperors and contested successions to imperial assassinations, some even verified

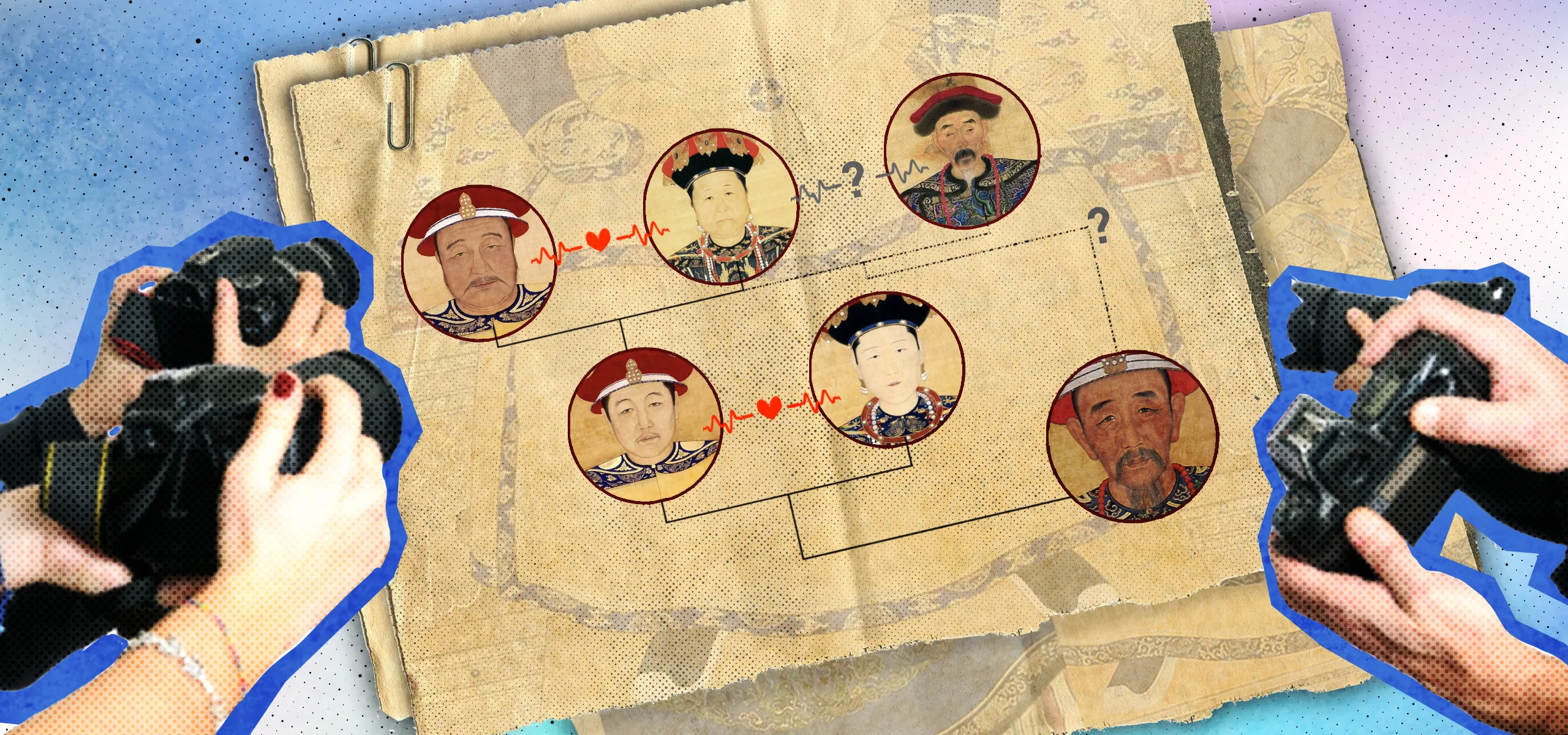

Recently, a centuries-old rumor has made a comeback online. It claims the Kangxi Emperor of the Qing dynasty (1616 – 1911) was the child of a Han Chinese general, swapped with the real emperor as an infant. Devoted netizens point to “evidence”: they compare Kangxi’s facial features with those of his ancestors in imperial portraits and scrutinize every detail of his complicated relationship with his father.

As China’s last imperial dynasty, whose official history is still in draft, the Qing has been a fertile ground for anecdotal accounts. Nearly every Qing emperor has inspired folk legends that often contradict official records. Here are some of the most widely shared—and most sensational—stories.

Kangxi Emperor: Secret Han agent?

The rumors making the rounds today on the Kangxi Emperor’s ancestry have far older origins than most think. According to the Draft History of Qing (《清史稿》), published in 1928, Hong Chengchou (洪承畴) was a general of the Ming dynasty (1368 – 1644) captured by Kangxi’s grandfather, Hong Taiji (皇太极), the leader of the Manchus who later founded the Qing dynasty. General Hong swore to never surrender, until Hong Taiji personally visited him in captivity and draped his own sable cloak over the general’s shoulders—an act that moved the general and persuaded him to give the Manchus a chance.

Discover the hidden stories of emperors in ancient China:

- Qianlong Emperor: The Worst Poet in Chinese History?

- Elixirs of Power: Chinese Emperors’ Quest for Immortality

- Ancient Snitches: How China’s Emperors Encouraged Informants

There had long been folk tales, though, that claimed Hong Taiji’s consort—later, Empress Dowager Xiaozhuang, Kangxi’s grandmother in real life—was the one who befriended and persuaded the general. Today’s netizens have spun the tale into an affair between the two, leading to a secret son. According to the rumor, when Hong Taiji’s grandson Xuanye (玄烨) was sent out of the capital to hide from a smallpox outbreak, the Emperor Dowager secretly swapped the prince, who succumbed to the illness, with her own son. He then became the Kangxi Emperor. Conspiracy theorists also point to an account from Korean envoys, describing the 9-year-old Xuanye as “robust as a 12 or 13-year-old” upon his return, citing as evidence of the princely swap.

There are nationalistic elements woven into this narrative. In the waning years of the Qing, many revolutionaries and reformers called for the overthrow of the emperors due to their Manchu ancestry and advocated for the establishment of a Han-led republic, arguing that Manchu rule had brutally oppressed the Han people and even destroyed their state. Today’s conspiracy theorists cite Kangxi’s vigorous promotion of Confucianism as “evidence” of his Han ancestry, and even historical events, such as an attempted coup led by minister Oboi’s clique, are said to be rooted in disdain for Kangxi’s disputed origins. The debate has recently drawn the attention of academics, including molecular anthropologist Yan Shi, who confirmed Kangxi’s imperial ancestry through genetic testing. Yet this scientific explanation has done little to dampen public appetite for speculation.

Yongzheng Emperor’s forgery

Conspiracies around Kangxi didn’t end with his death. Unofficial narratives also suspect his son Yinzhen (胤禛), later the Yongzheng Emperor, of scheming his way onto the throne. Since Kangxi never officially named an heir, his later years were marked by a brutal power struggle known as the “War of the Nine Princes (九子夺嫡).” The conflict only ended when the late emperor’s will, naming the Fourth Prince Yinzhen as the new emperor, surfaced three days after his death.

The atmosphere of plotting and secrecy created an ideal stage for rumors. The most popular claim holds that Kangxi’s original will named the 14th Prince as his successor. According to the theory, Yinzhen altered the text by modifying the characters “十四 (fourteen)” to “于四 (to the fourth).” This idea has been dramatized repeatedly in television series.

But a basic understanding of Qing history exposes a fatal flaw: Important documents like the emperor’s will would have been written in Manchu, Chinese, as well as Mongolian. Altering only the Chinese version would have been meaningless. Moreover, the character 于 would have been written in traditional form as 於 in 1722, making it impossible to modify from 十. In 2019, a replica of Kangxi’s will was displayed at the Beijing Municipal Archives, clearly affirming the Yongzheng Emperor’s right to succeed.

Qianlong Emperor: Was he even royal?

Theories about imperial parentage grew even more colorful in the third generation. Like his grandfather before him, the Qianlong Emperor was also given Han Chinese origins: In the martial arts novel The Book and the Sword, he is said to be the son of a Han official surnamed Chen from Haining, in present-day Zhejiang province. Author Jin Yong (金庸), also known as Louis Cha, was inspired by legends he had heard while growing up in Haining.

The tale is recorded in detail in the Unofficial Anecdotes of the Qing Court (《清朝野史大观 》), a 1917 collection of political legends and alternate histories. According to the account, while still a prince, the Yongzheng Emperor was close friends with Chen, whose son was born on the same day as Yongzheng’s daughter. The prince allegedly arranged for the two families to swap kids. Later in life, after learning of his true origins, the Qianlong Emperor visited the Chen family four times during his Southern Inspection Tours.

As Yongzheng already had several sons before Qianlong’s birth, this tale makes little sense. It was likely inspired by Qianlong’s genuine friendship with the Chen family and perhaps encouraged by their descendants and Haining locals for bragging rights.

The identity of Qianlong’s mother was even more disputed—all possibly owing to an administrative error. A posthumous edict issued in the name of Qianlong’s son, the Jiaqing Emperor, listed Qianlong’s birthplace as the Chengde Mountain Resort, contradicting numerous poems and official records that placed his birth in the Yonghe Palace. The next emperor, Daoguang, hurriedly issued a correction to the edict, adding that the Grand Councilors who made the mistake were punished.

As the Streisand Effect tells us, the quickest way to spread a rumor is to try to quash it. Already, there’d been whispers about Qianlong’s maternal lineage: A document from the Yongzheng era identified his mother, Consort Xi, as a Han woman called “Lady Qian.” Records from Qianlong’s own reign, though, referred to her as Lady Niohuru, a Manchu aristocrat. Now, the confusion over his birthplace fueled even more legends. One alleged that Lady Qian was a Han commoner who had a brief liaison with the Yongzheng Emperor at the Mountain Resort, but for political reasons, he arranged for the noble Lady Niohuru to adopt their son. Others suggested that the two were the same woman, and that Lady Qian was given a noble Manchu identity to elevate Qianlong’s status.

Adding to the mystique, the modern scholar Hu Shi (胡适) recorded another version in his diary in 1922, allegedly told to him by an old servant at the Mountain Resort. Supposedly, Qianlong’s mother was a southern woman nicknamed “Silly Elder Sister,” who cared for the Yongzheng Emperor when he fell ill. Hu’s diary put the legend into wider circulation and inspired numerous novels and TV dramas. The story of how a Han consort became Lady Niohuru is the central plot of 2011’s hit series Empresses in the Palace.

Emperor Guangxu’s poisoning (actually happened!)

Not all unofficial historical accounts are baseless. The long-circulated rumors regarding the death of the penultimate Qing emperor, Guangxu, were ultimately proven by science.

On November 14, 1908, the 38-year-old Guangxu Emperor died abruptly. A mere 22 hours later, his aunt Empress Dowager Cixi—who had dominated the Qing court for nearly half a century—also passed away. While the emperor’s death was officially put down to a sudden illness, the suspicious timing and the widely-known power struggle between the emperor and his aunt quickly fueled rumors that Guangxu had been poisoned. They were even repeated by Puyi, the last emperor of China, in his autobiography From Emperor to Citizen. Apparently, eunuchs had told him Guangxu had been in normal health just one day before his death, but deteriorated rapidly after taking a dose of medicine.

In 2008, modern technology finally unveiled the truth. Experts discovered abnormally high concentrations of arsenic in the late emperor’s hair, clothing, and remains. The total amount of arsenic in his body significantly exceeded the lethal dose. The findings were announced to the public in November that year, with experts saying they believed the Guangxu Emperor was deliberately poisoned (though they did not specify by whom). Surprisingly, nobody has put forward alternative theories—perhaps due to the complicated legacy of Cixi, or because any other explanation would be boring after all this trouble.

From power struggles to secret births, why do Qing court rumors maintain such enduring appeal? There could be many explanations: the incomplete nature of official Qing records, popular resistance to cultural suppression by the Qing court, and the influence of nationalism, both among late-Qing Han intellectuals and today’s netizens.

Yet perhaps the most fundamental reason lies in human nature—we inherently find dramatic storytelling more attractive than rigorous facts. As Jin Yong stated in the afterword to The Book and the Sword: “Historians, of course, dislike legends, but fiction writers love them. Moreover, any legend unfavorable to the imperial family would never find its way into official history.”