China’s next generation of factory owners, or “chang’erdai,” are stepping in, but slowing markets and shifting trade mean they must find new ways to keep their family businesses afloat

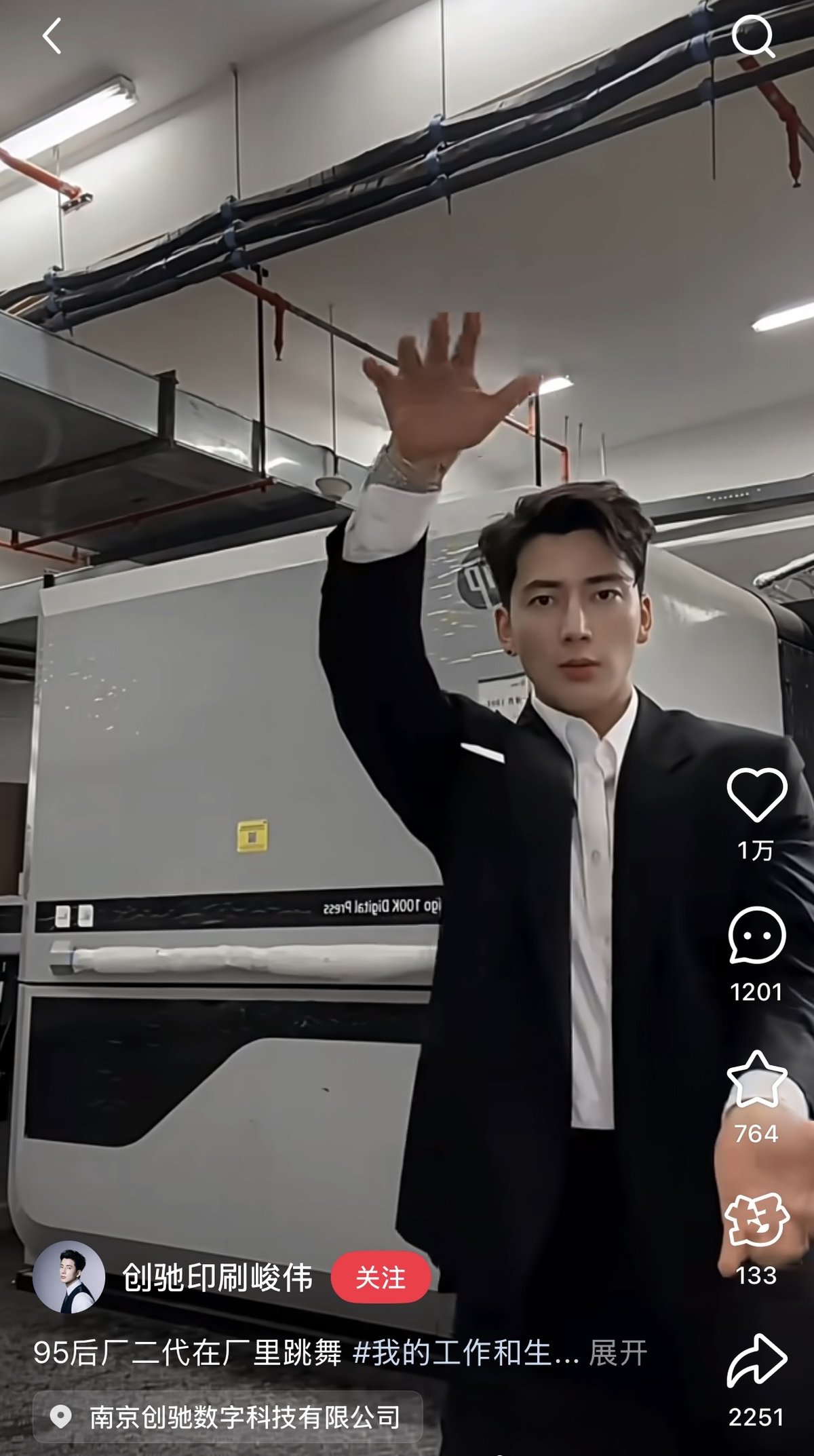

Junwei, dressed in a sharply tailored suit with his collar undone, sways a little awkwardly to a viral song on Douyin, China’s version of TikTok. With his polished looks and gelled hair, the 20-something could easily pass for another influencer. But at the center of the frame isn’t Junwei—it’s a massive industrial printer, while he dances off to the side on the gray factory floor. Junwei isn’t just chasing views; he’s fishing for clients for his family’s digital printing business, and his profile offers little personal information but a brief factory introduction, details about its equipment, and contact information. Even his handle—Chuangchi Printing Junwei—doubles as an advertisement, Chuangchi being the company’s name. With 110,000 fans on Douyin, he has successfully converted online traffic into both revenue and new clients for the printing factory.

Junwei is far from alone. Across China, a growing number of young people—collectively known as “chang’erdai (厂二代),” literally second-generation factory owners—are turning to social media to showcase and promote their family businesses. Under the tag “chang’erdai,” they post everything from casual vlogs about daily life on the factory floor to elaborately staged short dramas detailing their parents’ rags-to-riches stories, racking up billions of views and feeding outsiders’ curiosity about the lifestyles of the wealthy and sparking interest in these young heirs’ paths to succession. The trend has even inspired a reality show on streaming giant Mango TV.

Read more about Chinese factories:

- Amid Snags in Global Trade, Chaozhou’s Wedding Dress Factories Battle to Survive

- In Southern China’s Once-Thriving “Garment Kingdom,” Business Fades Amid Urban Renewal

- Behind the Scenes at China’s Christmas Factories

China, dubbed the “world’s factory” after the turn of the century and having officially surpassed the US in manufacturing output in 2010, is now seeing its first wave of private factory owners edge toward retirement, nudging their children—post-90s and post-00s generations who, on average, grew up with better living standards and educational opportunities—toward the helm.

But in reality, what this new generation inherits is rarely a gold mine. With global demand for products cooling, domestic consumption sputtering, and geopolitical tensions fueling trade wars, many family factories are under strain. To keep them afloat, young successors are attempting to rewrite the playbooks: moving sales online, cutting out the middleman to reach customers both domestically and internationally, and building personal IP on social media—bold steps their parents might neither understand nor entirely support.

According to government data, there were over 6 million manufacturing companies in China in 2024. Researcher Zhang Zhipeng told the 21st Century Business Herald in 2023 that there are roughly 45,000 to 100,000 chang’erdai who have or are in the process of taking over their family businesses. For some, coming home to run these factories is a no-brainer.

“There was no special reason for me [to take over], just carrying on the family business, I guess,” says Ma Leimeng, who started to work in the family’s clothing fabric factory in Zhejiang’s Wenzhou city after graduating college in 2014. “With a family factory already in place, I get a better start than if I were just working for someone else.”

Ma, a graduate in e-commerce, began by handling random tasks at the company and gradually worked his way up to managing director. “You’re always clumsy with new things, so it’s a matter of learning day by day and asking questions. It’s not hard—it’s only a problem if you don’t want to learn,” says Ma.

His path mirrors that of many chang’erdai returning to family factories in provincial manufacturing hubs such as Zhejiang, Jiangsu, and Guangdong. But while many have documented the gnitty-gritty of learning the ropes and completing daily tasks online, some videos also show these next-generation owners waking up in sprawling mansions, wearing luxury brands, and driving high-end cars to work. This has only reinforced the stereotypes the internet has already pinned on them—that they are wealthy, pampered, and out of touch—even as they try to prove otherwise.

While Ma acknowledges the comfortable life his parents’ hard work afforded him, he also stresses the reality behind it. “Only those who’ve actually taken over know how tough it is. The foundation the older generation built can support you, but without your own effort, it won’t last.”

For Zeng Tian, who left her corporate job in Shanghai last year to help run her fiancé’s family’s glass crafts factory in Quzhou, Zhejiang province, these stereotypes are simply not true, at least not for heirs of small-to-medium factories like theirs.

“Every day his mind is full of orders and inventory, and he’s always slogging away in the factory,” says Zeng, adding that they sometimes get only one day off per month. Her fiancé, Ye, who requested use of only his last name, receives a monthly salary of 7,000 to 8,000 yuan from his mother, the factory’s accountant—just enough to cover basic expenses. He must also cover shortfalls out of pocket when advancing payments for certain orders.

Given the current economic climate, Ye’s parents even had reservations when he chose to take over the family business rather than continue his well-paying sales job in Shanghai’s new energy industry. But feeling that his previous company offered no long-term growth or career development prospects, Ye eventually returned to take over the family business in 2023—with Zeng’s encouragement. “Why sell for someone else when you can sell your own products?” she says.

However, they soon realized that the market is far more challenging than they had anticipated. According to World Bank data, the share of China’s manufacturing value added in GDP fell from 31 percent in 2010 to 25 percent in 2024. This fall is partly attributable to US President Donald Trump, who imposed sweeping tariffs on Chinese imports after taking office in 2017. Then, after the start of his second term earlier this year, he raised tariffs by as much as 145 percent on select Chinese goods and ended the de minimis exemption that had long benefited major Chinese e-commerce exporters like Temu and Shein. The EU also imposed tariffs on Chinese EVs and steel.

“In the past few years, as foreign trade declined and orders dried up, factories have been shutting down one after another…In our county, we’re now the only factory left making products like ours,” says Zeng.

For decades, export-focused factories like theirs have relied on foreign trade companies to place orders rather than work directly with clients. But “orders from foreign trade companies have plunged by more than half in recent years,” says Zeng. With the economic downturn, she and Ye have been trying to reach foreign importers directly to save on hefty commission fees imposed by middlemen. They have also begun supplying small sellers on Amazon and Temu, which offer attractive profit margins despite smaller order volumes.

Social media has become invaluable for reaching clients. This, in turn, has meant that within China, many chang’erdai have become influencers, spinning the stories behind their factories into personal brands. Makers of finished products such as toys, purses, and water bottles sell directly on Douyin and Xiaohongshu, offering lower prices than resellers. And when Trump reignited the trade war earlier this year, the so-called “Chinese warehouse TikTok” trend—where Chinese workers shot videos to expose the origins of major international brands’ products—highlighted how foreign buyers could directly connect with manufacturers.

Many factories have since followed suit, posting videos on TikTok to showcase their production processes and finished products, as well as opening TikTok Shops to sell straight to consumers. China Newsweek reported in October that 42-year-old chang’erdai Chen Xing, from the major Zhejiang manufacturing hub of Yiwu, now sells laser hair removal devices via TikTok, earning approximately 5 million US dollars a year. The businessman described how the platform gives him direct access to consumer feedback and greater pricing freedom, easing the pressure the previous generation faced from clients to slash prices.

Chen’s success is not easy to replicate, however, as online trends shift rapidly. The formula for virality—if attainable at all—is also often very different for each brand, and with more people entering the field, it’s increasingly difficult to stand out. Ma points out that direct B2C sales don’t work for all factories, especially those that only manufacture source materials or components rather than finished goods. “New clients we know nothing about, especially in foreign trade, are very risky to work with,” he says, cautioning about fraud and potential cash flow disruption when doing business with clients from social media.

Despite these risks, Zeng is clear about the benefits of having an online presence. “Your account serves as a kind of social business card. If you’ve already posted over 100 videos and a potential client comes across your TikTok, seeing all the content you’ve created naturally builds trust. That’s why I think this is about more than just generating traffic,” she says.

She’s been building the factory’s overseas social media accounts over the past year, but has yet to gain significant traction or attract consistent orders. This has created some friction with her future in-laws, who are more result-oriented.

“At my previous company, work and personal life were clearly separated. But in a family factory, you can’t separate the two,” says Zeng. “My fiancé finds it even harder to communicate with his parents than I do. That whole [first] year, there were arguments almost every day, over things big and small.”

Intergenerational conflict is common among chang’erdai and their parents, with the new upstarts often having different approaches or perspectives that their elders are unaccustomed to. “For example, we, the new generation, think the customer comes first—whatever the client asks, we need to make changes immediately,” Zeng explains. “The older generation, however, feels that for a small cross-border e-commerce order, there’s no way they’re going to go back and source new materials.” It took her a year to convince her in-laws that Amazon orders are worthwhile.

Ma has also struggled to convince his parents to be more aggressive in launching new products. These frustrations are echoed on social media by other chang’erdai. A popular post on Xiaohongshu details one of the biggest issues facing chang’erdai: The older generation isn’t willing to relinquish control. On paper, chang’erdai are the new bosses, yet their parents still treat them like children.

Zoe Xie, a 25-year-old from Guangdong, is all too familiar with the struggle to be taken seriously, especially as a woman in the traditionally male-dominated manufacturing industry. After graduating from Johns Hopkins University with a degree in biology this past summer, she joined her father’s company, Precise Direction, which produces high-end, tech-integrated furniture for villas and hotels, catering to many overseas clients.

“People see that I’m a woman and that I look very young, so they immediately assume I’m inexperienced and just there to chit-chat and provide emotional value,” says Xie. “Even some translators don’t take me seriously when I was abroad attending conferences.”

She has resorted to dressing more professionally and equipping herself with a deep knowledge of the company’s products, determined not to let others’ prejudices stand in the way of helping her father realize his dream of building a large, highly automated industrial park—something he’d been planning for more than two decades. And while her parents never expected her to take over, and supported her in pursuing her own dreams, she finds the job gradually growing on her.

“My parents’ vision impressed me. They’re nearly 60 and decided to build a new factory in such a tough market. It’s an undeniably risky move,” says Xie. “I felt it was necessary to go back and help them, to support their dream.”

The new 79,000-square-meter park is set to open in 2026 and will closely echo the priorities outlined in China’s latest Five-Year Plan, which emphasizes technological upgrading, smart manufacturing, and higher-value production.

“Our new factory will be about four times the size of our current one, but the number of employees on site will likely stay the same,” says Xie.

She mentions that while about half of their clients are from the US, the tariff war didn’t affect them much. “Factories in Southeast Asia don’t have the technology to produce our products. Our clients say we’re still their best option even with the tariffs,” says Xie. “Factories like ours would probably take them another 20 years to catch up.”

She plans to build the company’s social media accounts and websites to reach and take on a more diverse range of clients after the park opens. “I don’t have to focus only on Europe or the US, because we also have clients in the Middle East and Africa. Expanding to different markets lets us avoid relying on a single region and reduces our dependence on tariffs or a single country’s policies,” says Xie.

Having watched numerous videos posted by other chang’erdai, Xie is determined to create content with a more serious bent. Still, she acknowledges that building a large following is already an achievement in itself.

“Every chang’erdai has to find the succession path that works best for them,” she says.