Once a constant companion of commuters and late-night listeners, radio stations in China are shuttering amid declining listenership and shrinking advertising revenue. But the medium’s core elements are reemerging elsewhere in new forms of listening.

Lucy Gu struggled to believe the news when she first saw it on social media last December: Hit FM (FM 88.7 in Beijing or FM 87.9 in Shanghai), her favorite radio station, was shutting down. It sounded like a rumor—until the morning of December 23, when the channel disappeared from her app. She assumed it was a glitch until she got into her car and realized FM 88.7 was gone there, too. She sat quietly in the car, letting the news sink in.

“The closure dealt a really big blow to me,” says Gu, a Beijing resident who had tuned in to the local station for 15 years. Whether driving or out for a run, the channel was a constant companion. Even in the age of streaming, Gu, now in her 50s, kept a dedicated app on her phone, just so she could listen wherever she went.

For many Generation X and millennial listeners, the channel was the first introduction to Western music and pop culture. Launched in 1999 as a domestic multilingual broadcasting service, Hit FM transformed into a station primarily airing pop music from Europe and the US in 2003.

“[The channel] was like a teacher,” says Conney Wang, a listener for over 20 years. “Immersed in its songs and DJs’ voices, I always got good grades on English in school—and I’ve always said the secret to speaking good English is listening to English songs.”

At its peak, Hit Music FM was broadcast to multiple large- and medium-sized cities across China.

“The list of frequencies [for different locations] alone used to take nearly a minute to read,” recalls Wang, now in her 30s.

But by the time it went off air, the station was broadcasting only in Beijing and Shanghai.

Wang and Gu are not the only ones to have had to say goodbye to their favorite channel in the past year. An unofficial count based on public closure announcements shows that more than 40 radio stations closed in 2025.

But while radio in China appears to be losing public attention, it is too early to conclude that the medium is fading entirely. Its core function—providing a stable, low-cost form of public connection—continues to thrive in the digital age, albeit in different forms.

Read more about radio in China

- The Rasping on the Radio

- Tangled Web of Wired Radio

- Arms Up! How Radio Exercises Live on in Modern China

The golden age of radio

The first radio station in China was established by American journalist E.G. Osborn in Shanghai in 1923. During the ensuing decades of war, radio served as a major and powerful propaganda tool, broadcasting rousing songs and inspiring speeches to mobilize and unite the Chinese people against Japanese aggression.

On October 1, 1949, the founding of the People’s Republic of China, broadcasters delivered live coverage from central Beijing’s Tiananmen Gate Tower, with radio stations nationwide carrying the program simultaneously. The over six-hour broadcast marked the country’s first large-scale live transmission.

Radio continued to play a fundamental role in the economic recovery and local governance in the decades following. At a time of poor transportation, low literacy rates, and limited newspaper circulation, wired radio was the most effective means of spreading news to every corner of the country, especially to remote rural areas. People would often gather around loudspeakers to listen to news, patriotic songs, and policy announcements from the central government. The number of local radio stations nationwide more than tripled between 1950 and 1960, reaching 145 by 1962.

During China’s “reform and opening-up” period of the late 1970s, as household radios and car audio systems spread, the listening experience became more personalized. Radio stations began developing programs tailored to different audiences and listening contexts, while content expanded to include news, music, traffic updates, sports, business, and culture.

In 1986, Zhujiang Economic Radio in Guangdong province pioneered a new format: continuous rolling broadcasts with live hosting and listener participation via hotline. The model broke from traditional script-led programs, giving hosts greater creative freedom and fostering stronger connections with listeners. In its first month, radios sold out across Guangzhou, the station’s hotline was flooded with calls, outdoor events drew crowds of 70,000, and listeners’ letters piled up in the corridors of the editorial office. Late-night shows following this model, where hosts answered questions about relationships—sometimes veering into racy territory—became especially popular in the 90s.

Closure and transition

By the 21st century, the battle for audience attention was in full swing, with radio contending with two more visually compelling media: TV and the internet. The number of traditional radio listeners fell from 683 million in 2018 to 610 million in 2024, while online radio audiences tripled over the same period. Radio’s advertising revenues also fell sharply from 15.6 billion yuan in 2017 to 6.7 billion yuan in 2023. Many stations—over 100 nationwide since 2023—have reportedly shut down to reallocate resources to digital and new media platforms.

However, Li Jiangang, an associate professor of audio journalism at Communication University of China, argues that the trend is not simply a response to the rise of digital media but reflects a more fundamental policy shift. At the national level, the government is repositioning radio’s role in the national communication framework. A May 2023 announcement by the National Radio and Television Administration stated that China’s broadcasting system would “actively advance the integration of radio and television resources and streamline operations.” From April 2024 to December 2025, 85 radio stations at the city level or above were taken off the air.

“China’s radio has increasingly been pushed to operate under market logic and efficiency-driven reforms,” says Li, “especially through media consolidation and platform-style management.” He adds that, in contrast, Western broadcasters like the BBC have long been considered part of society’s public cultural infrastructure, serving educational and public service roles. Their legitimacy, Li notes, does not depend on market performance.

Many radio broadcasts in China have also merged with other channels, frequencies, or digital platforms. On the same day Hit FM went off air, two other radio services under its parent company, China Radio International, were also shut down. The official announcement noted that listeners could continue to access international pop music through platforms such as China National Radio’s Music Radio or Yangshipin, an app run by the state broadcaster CCTV, among other new media channels.

“This is a systemic transition,” Li tells TWOC. “Against this broader backdrop, content redistribution is still being adjusted, and clearer information will likely emerge from the authorities this year.”

Reconnecting in new places

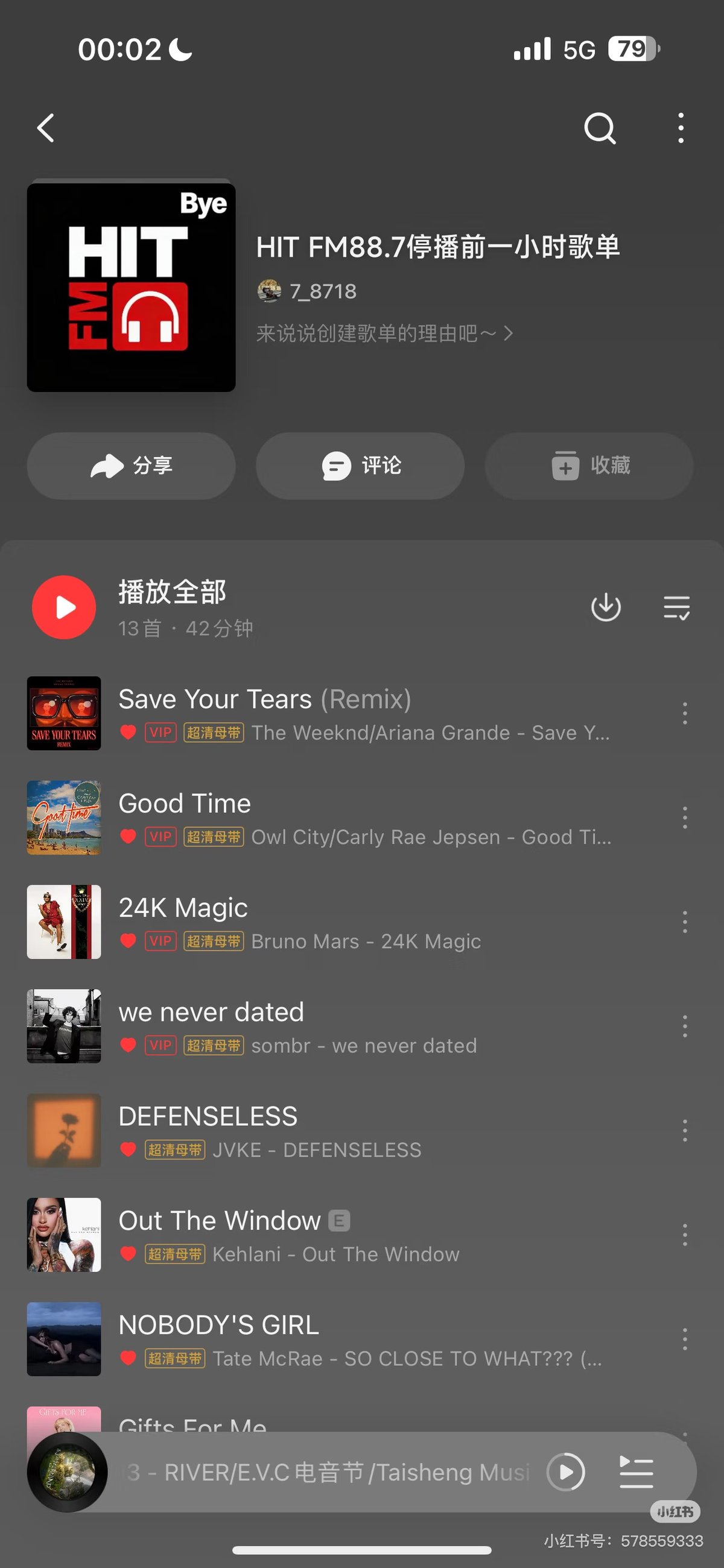

While many listeners are aware of public radio’s struggles in recent years, channel shutdowns still feel abrupt, often announced just days before taking effect. In Hit FM’s case, rumors had circulated online prior to its closure, but the official notice came at 9:44 a.m. on December 22—less than 24 hours before the station went off air at midnight, as Owl City and Carly Rae Jepsen’s “Good Time” played its final notes.

“Hit FM wasn’t just about Western pop music, but also the DJs—the emotions and sense of connection they carried. When all of it suddenly disappeared, ‘loss’ was the only word that could describe how I felt,” says Gu.

Many listeners have also taken to the internet to reminisce about the shutdown. On Douyin, the tag “Hit FM shutdown” has drawn more than 1.37 million views. Li, the professor, believes that this wave of collective nostalgia reflects radio’s overarching power: its ability to bind people together, whether they listen alone or together. As a low-interference, continuous, non-visual medium, radio slips easily into the rhythms of daily life. When a station goes silent, it’s more than just content that disappears—it’s a quiet companion and public voice that leaves too.

But as individual channels go dark, many listeners are discovering that their preferred form of entertainment hasn’t vanished completely—it has just taken on new forms.

This January, more than 150 longtime listeners from across the country met at a Beijing music bar to reunite with Hit FM’s four former hosts in person. During the event, they spent the afternoon sharing memories and playing games. Some attendees even brought their children, an indication that the radio’s emotional imprint extended beyond individual listeners and into family life. In the event’s closing moments, one of the former hosts remarked that although the station has ended, their passion and love for music would never fade, and that they would find other ways to meet again.

“I truly feel like I’ve found my community,” says Gu, who attended the event—her first fan gathering. She now follows several former Hit FM hosts online, watches their livestreams when she has time, and interacts with them on digital platforms. Many such hosts, after being pulled off air, have since migrated to platforms such as Xiaohongshu, NetEase Cloud Music, Ximalaya, Xiao Yuzhou FM, and WeChat livestreaming.

Wang, meanwhile, says she has yet to find a replacement for the station, but has turned to online recordings of past Hit FM programs.

Platforms have begun to recognize the enduring value of such connections formed over decades. Bilibili recently launched a “Radio Host Support Program,” inviting radio hosts from major stations to join the video streaming platform. According to public statements, it plans to invest billions of yuan in cross-industry collaborations, production support, and operational assistance to encourage the creation of video podcasts and music radio programs—an effort to ensure that the music and voices that accompanied generations of listeners do not simply fade away.

The future of radio

For many late millennials and younger people in China, radio was unlikely to have played a formative role. Nevertheless, these listeners are forming a similar sense of connection with new audio formats, such as podcasts.

“What podcasts mean to me might be what radio was to older generations,” says Manga Zhang, a 29-year-old who has logged 1,284 hours of listening on podcast platform Xiao Yuzhou FM. Like radio audiences before her, she tunes in during her commute and feels a strong connection to the hosts. She once wrote to a show, and eventually appeared on it as a guest. “To me, what makes podcasts special is exactly that—a genuine, human-to-human connection.”

Industry estimates suggest that last year, the number of podcast listeners in China exceeded 150 million, with the majority aged 25 to 40.

Public radio, meanwhile, continues to prove itself a valuable tool in emergency contexts, with the construction of an emergency broadcasting system explicitly included in the national 14th Five-Year Plan (2021– 2025). During a 2022 typhoon that struck off the coast of Shandong province, 35 emergency messages were broadcast, reaching over 3,000 individuals. Following the alerts, more than 400 vessels returned to port, reducing economic losses by an estimated 1 million yuan.

“I believe the value of radio doesn’t lie in traffic or audience numbers, but in providing a stable and trustworthy form of public connection,” Li, the professor, concludes. “Radio has taken on different roles and appearances—such as car radio, emergency broadcasting, and service-oriented media aimed at specific groups. This reflects that it will remain part of a broader public system.”