Why China’s thrill-seeking livestreamers broadcast from ‘haunted’ locations

Wanted: brave soul to live stream from a haunted house. Must be “unafraid of listening to ghost stories in the middle of the night,” “a committed atheist,” and “a believer in science.” Payment: 1 RMB per minute, and perhaps a spooky experience.

The job advertisement, which recruited livestreamers to record themselves spending 24 hours in a “haunted” apartment for sale in Suzhou, appeared on Alibaba Auction on December 3 and quickly went viral. Twelve hours later, staff said they had already received over 100 applications from candidates as diverse as a physics teacher and a journalist. The hashtag, “Alibaba Auction responds to haunted house livestreamer job ad” had been viewed nearly 20 million times on Weibo at the time of writing.

It may seem like a strange profession, but China’s livestreamers have been exploring spooky structures for some time now, and making money from it. “The rule is that to enter the industry, you must first train your courage”, Da Ji, a 30-year-old “nighttime exploring host” who has worked as a livestreamer for four years, claimed in a podcast for Gushi FM in January this year.

Da Ji and her fellow explorers seek out old hospitals, abandoned villages, and other dilapidated structures to investigate, and provide a thrill to their followers. Their videos have earned hundreds of thousands of views on streaming platforms like Bilibili and YY TV. In one video, Da Ji explores an old brothel in Harbin that dates from the time of Japanese occupation of Manchuria. She enters the building in pitch darkness, armed with only a selfie stick, two phones, a portable charger, and a flashlight.

In another video she visits an abandoned village in Hunan province, hiking for 6 hours along the ridge of sheer cliffs to get to her destination. There, she found homes containing coffins and portraits of the deceased, and rotting meat left as offerings for the dead.

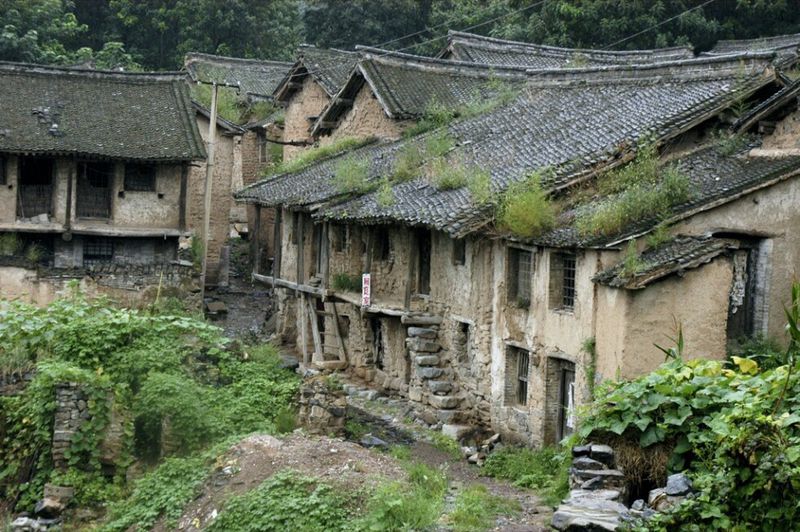

Abandoned villages are popular among spook-seeking livestreamers (VCG)

The old abandoned villages are big sellers, Da Ji claimed, because urban viewers enjoy the traditional architecture, and the ghost tales which often accompany such places. Many of the places explorers visit have spooky stories of the supernatural attached to them, or were the site of murders or other tragedies (though Da Ji avoids filming funeral parlors and crematoriums, and sites of “national disasters” like the 2008 Wenchuan Earthquake).

Though perfect playgrounds for intrepid, thrill-seeking livestreamers, “haunted” properties (凶宅 xiōngzhái), in which tragedies have taken place, can pose a problem for property owners and real estate agents once they gain their cursed reputation. In the past, the price of homes have plummeted after they became known as xiongzhai.

An apartment in Dalian, in which a 13-year-old boy is accused of having killed a 10-year-old girl, couldn’t be sold even with a 140,000 RMB discount. A property in a desirable area of Nanjing that saw an “unnatural death” received no bidders in 2018, despite a price cut of 1.6 million RMB on the original 8 million RMB listing. This may explain why the estate agents in Suzhou are willing to pay someone to livestream and prove the house isn’t haunted.

Or, perhaps, it was just a marketing technique. In March, an episode of I’ll Find You a Better Home, a TV show that focuses on the lives of estate agents, brought up the issue of how to sell a xiongzhai. After the episode aired, viewers went online to vent their frustration against agents’ uses of “haunted house” adverts to drive traffic to their site. According to The Paper, agents have been known to falsely label some online homes as “haunted,” and advertise them at a large discount with eye-catching spooky images, all to drive traffic to the other properties listed next to them online.

A historic district in Harbin was the site of one of Da Ji’s most popular broadcasts, which explored an abandoned brothel (VCG)

In the event that a buyer does wind up buying a “haunted” dwelling unawares, the courts have proven remarkably receptive to their complaints—though this may be in compensation for the lost property value, rather than any ghosts. In a case from 2017, a Mr. Zhang from Beijing successfully had his housing contract annulled and his money refunded after he discovered the apartment he bought was the site of an unnatural death under the previous owners. When Mr. Zhang took the matter to court, the judge ruled he should have been informed on the apartment’s xiongzhai status.

The “haunted” label may have weight in law, but Da Ji doesn’t believe in ghosts, and says her work isn’t about finding the supernatural. “My principle is, ‘Explore for danger, not for ghosts, and do away with feudal superstition,’” she claimed to Gushi FM.

Despite this, streaming sites have blocked videos like Da Ji’s, apparently suspecting them of promoting superstition. And even Da Ji admits to being creeped out from one video she filmed in the former brothel in Harbin: “When I filmed it, there was no noise; but when I reviewed the video, you could hear a girl crying.”

Cover Image from VCG