Magpies for happiness, cuckoos for sorrow, and cranes for longevity—learn the symbolism of birds in China

With spring in full swing, birdsong fills the air in much of China. And just like many plants and creatures in China, birds can represent a range of different qualities, from sorrow (the cuckoo) to longevity (the crane) and romance (mandarin ducks).

Here are some symbolic birds that often appear in Chinese poetry, literature, and tradition:

Magpie: happiness and good luck

The magpie is “喜鹊 (xǐquè)” in Chinese with 喜 meaning “happy,” and perhaps because of this name they are often associated with good luck. In Li Shizhen’s (李时珍) Compendium of Materia Medica (《本草纲目》), a 16th-century Chinese medicine volume, the renowned physician wrote that magpies are “smart and can report good news, so they are called xique.” Even earlier, in the Spring and Autumn period (770 – 476 BCE), author Shi Kuang (师旷) asserted in his Encyclopedia of Birds (《禽经》): “Magpies bring good news.”

In the Manchu-led Qing dynasty (1616 – 1911), magpies were even worshiped as divine due to their role in the creation myth of the Manchu people, who believed they originated from atop Changbai Mountain on the border of China and North Korea today. The Veritable Records of Qing Emperor Taizu (《清太祖实录》), a book on the formation of the Qing empire, records the legend: Three fairies were playing in Tianchi Lake, at the summit of Changbai Mountain, when a magpie holding a red fruit in its beak flew past. One of the fairies managed to snatch the fruit, and ate it. Before long, she became pregnant and later gave birth to a boy—the earliest ancestor of Manchu people.

In Manchu culture, magpies were revered: During rituals and sacrifices made to the gods, they would prepare food for the birds too.

Magpies also play an important role in Han mythology. In the story of legendary lovers Niu Lang and Zhi Nǚ, who were separated by a god named the Queen Mother of the West, and only allowed to meet once a year during the Qixi Festival (now a kind of Valentine’s Day in China). In the story, magpies gathered together to form a bridge over the Milky Way so that the lovers could be together.

Cuckoo: sorrow and depression

In Chinese literature, the cuckoo (杜鹃 dùjuān) is nearly always used as a symbol for sorrow. Countless famous poets invoked the bird in their works. For example, Tang dynasty (618 – 907) poet Bai Juyi (白居易) once wrote, lamenting his own living conditions: “What is here to be heard from daybreak till nightfall / But the gibbon’s cry and the cuckoo’s homeward-going call?” Li Bai (李白), another famous Tang poet, wrote the line: “Every time a cuckoo cries, my heart breaks into pieces.”

This reputation began with another legend. Over 3,000 years ago, in the region around today’s Sichuan province, there was a successful ruler named Du Yu (杜宇) who led his subjects to develop agriculture, and became known as “Emperor Wang (望帝).” But Du’s one shortcoming was his inability to control the floods, a job which he left to his chancellor Bie Ling (鳖灵). Bie was brilliant at it, and earned Du’s praise and a promotion. But instead of being grateful, Bie betrayed Du and usurped the throne.

Du went into exile, and died of depression soon later. After death, Du was reincarnated as a cuckoo bird, who cried all day and night.

Since then, cuckoo has been closely associated with sorrow, depression, and sadness. And the name of the ruler, Du Yu, became a byword for the cuckoo, often used interchangeably with the name of the bird in literature.

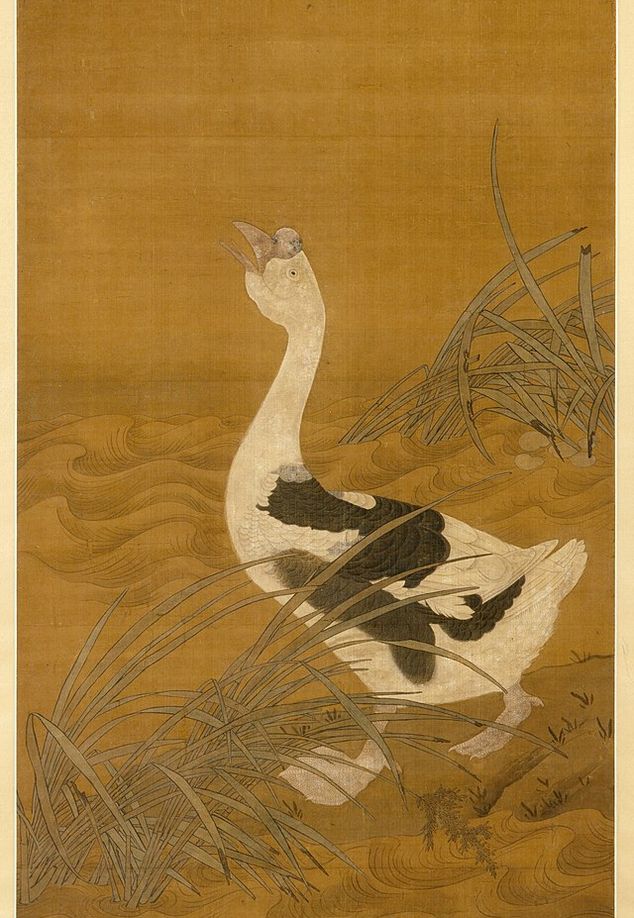

Wild goose: loyalty, integrity, and love

Among all birds, the wild goose (雁 yàn), probably has the most virtues in Chinese tradition. They are seen as benevolent, because they always fly in groups and the young and healthy birds don’t give up on the weak or old; they are disciplined, because a flock of wild geese can always keep formation; they are trustworthy, because they regularly and reliably migrate from north to south. And most importantly, they are believed to be loyal lovers that only have one partner for life.

Jin dynasty (1115 – 1234) poet Yuan Haowen (元好问) once recorded a story of a hunter who told him he had captured a wild goose and killed it. But another wild goose, who had managed to escape, flew back in search of its partner. After seeing the other goose dead, it uttered a cry, and dove straight into the ground head first in an apparent act of suicide.

Moved by the love between the pair of wild geese, Yuan wrote a poem named “The Tune of the Wild Geese Tomb (《雁丘词》),” which contains a line now familiar to many Chinese: “Can someone tell me, what love is supposed to be? That makes death a beauty as long as you are with me.”

Crane: longevity and nobility

In China, cranes (鹤 hè) are associated with longevity and are often referred to as “immortal cranes (仙鹤),” because the bird is often associated with immortal gods in mythology. In many legends and folktales, deities from heaven ride a crane to fly to the human world. For example, in the classic 16th-century novel Investiture of the Gods (《封神演义》), the immortal Taiyi Zhenren, a reincarnation of the first emperor of the Shang dynasty and teacher of Nezha, rides a black-feathered crane.

In Daoist culture, the crane is regarded as a messenger from heaven. When a Daoist priest dies, an immortal crane is said to come to take him to heaven. In Chinese, the phrase “ride a crane to the west (驾鹤西去 jiàhè xīqù)” is a euphemism for someone’s passing.

To compliment an elderly person who looks healthy and youthful, one can say they “have a crane’s gray hair and a child’s face (鹤发童颜 hèfà tóngyán).” A common gift for the elderly is a painting featuring a crane and pine trees, because of the idiom “pine and crane prolonging life (松鹤延年 sōnghè yánnián).”

Besides longevity, the crane is also regarded as a symbol of nobility and integrity. Ancient people often compared talented and virtuous individuals to cranes. Zhou Lüjing (周履靖), a Ming dynasty (1368 – 1644) scholar, wrote in A Book on Cranes (《相鹤经》) that “cranes walk in a disciplined way, just like a nobleman...its song is loud and clear, impressive as a talented person.” Indeed, during the Qing dynasty, the highest-ranked civil officials were identified by a crane motif embroidered on their robes.