As the Han empire crumbled and the Yellow Turban Rebellion sought to overthrow imperial rule, the “Way of the Five Pecks of Rice” quietly planted the roots of a durable Daoist movement

As natural disasters, epidemics, famines, sky-high taxes, corruption, and warlords ran rampant across territories of the crumbling Han empire in the late 2nd century, the peasants began to do what they do best—rebel.

Millions famously took up arms in the Yellow Turban Rebellion (黄巾军, named after the yellow kerchiefs followers wore during battles), led by the Daoist healer Zhang Jue (张角), and tried to violently topple the Han regime in 184. But while Zhang Jue’s attempt to implement Daoist governance by force of a “celestial revolution” is well-known in Chinese history, another Daoist movement around the same time was more successful and perhaps more influential. Indeed, just six years after Zhang Jue and his army were crushed in 185, an independent Daoist state was established in Han territory which would last 25 years and influence the future of Daoism to the present day.

This religious movement, known as the “Way of the Five Pecks of Rice (五斗米道)” or “Way of the Celestial Masters (天师道),” was led by Daoist healer Zhang Daoling (张道陵) and later his grandson Zhang Lu (张鲁), and its legacy remains through Daoist followers today who adhere to the “Way” set out by the Zhangs and those who claim direct lineage from these leaders. Zhang Meiliang, who lives in Taiwan, claims the title of 65th Celestial Master today, while Longhu Mountain in Jiangxi province remains a sacred place for followers of the Way of the Celestial Masters on the Chinese mainland.

The grandfather Zhang began preaching to the masses after he had a vision of Laozi, the reputed author of the central Daoist text, the Dao De Jing (《道德经》), atop Mount Crane Call in the State of Shu (present day Sichuan province) in 142 and assumed the title “Celestial Master (天师).” The Extensive Records of the Taiping Era (《太平广记》), a collection of historical stories written in the 10th century, recorded the moment: “A heavenly man descended, accompanied by a thousand chariots and ten thousand horsemen, in a golden carriage with a feather canopy…At times the man referred to himself as the Scribe Below the Pillar, sometimes he would call himself the Lad from the Eastern Sea.”

Zhang Daoling appealed to those suffering from the vicissitudes of the era. The Book of Later Han (《后汉书》), a historical record of the era compiled in the fifth century, recorded that in the summer of 171, “a severe drought broke out, and locusts appeared in seven provinces,” then in early 177 “there was an earthquake, and the sea overflowed.” But while the Yellow Turbans called for followers to overthrow the Han empire and its capital, the elder Zhang offered a more individualized, spiritual, and inward-looking set of solutions to commoners’ plight.

Zhang Daoling maintained that a person’s physical illness represented the outer manifestation of inner depravity, which he offered to heal. Zhang’s faith-healing technique called on adherents to write down a confession of their sins (potentially responsible for their sickness), then throw the paper into a river and solemnly promise to the gods that they would never transgress again. For these teachings, followers had to pay rice, silk, or household utensils. The amount of rice was set at five pecks; hence the movement’s other name.

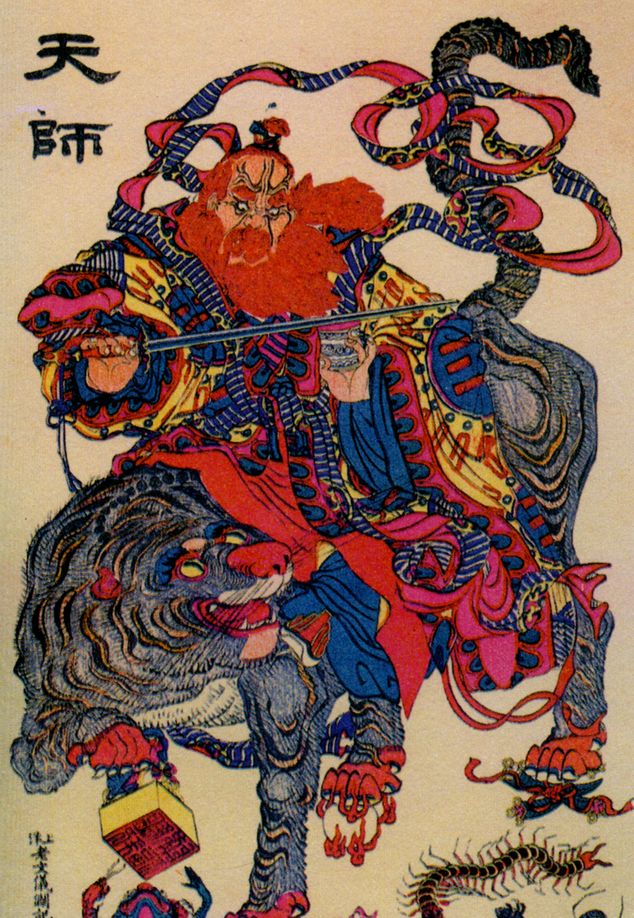

A painting of Zhang Daoling, who was later known as Zhang Tianshi (Celestial Master Zhang), driving away evil spirits (VCG)

Those who received this healing began to live together, forming a community with Zhang as its head. They would often bring their entire families, and farm and worship together. Under the grandfather Zhang, “commoners flocked to serve him as their teacher. His disciples came to number several tens of thousands of households,” according to Ge Hong’s (葛洪) fourth century text the Biographies of Deities and Immortals (《神仙传》). The congregation of followers and formalization of various hierarchical structures meant that “Zhang Daoling and his followers clearly effected a religious revolution…the social history of Daoism begins with the founding of the Way of the Celestial Master in the second century,” according to historian Michel Strickmann.

By the time leadership of this burgeoning Daoist community passed to Zhang Daoling’s grandson, Zhang Lu, via the elder Zhang’s son, Zhang Heng (张衡), the community had assigned specific roles and titles to adherents who came to the southwest in search of spiritual remedies for their troubles. New converts were known as guizu (鬼族, demon troops), possibly because they were still fighting inner demons, while older followers who had undergone training were called jijiu (祭酒, libationers) and took charge of religious teaching. Zhang Lu continued to emphasize the importance of cleansing the soul but modified the original healing technique: the name of the follower and their sins were written on three pieces of paper, with one burnt, one buried, and one submerged in water.

Initially this religious community blossomed within the confines of the Han empire, with Zhang Lu serving as a military official for Liu Yan (刘焉), regional governor of Yi province (present-day Sichuan). But even though Zhang’s Daoist movement was not as overtly violent or power hungry as the Yellow Turbans—who waged open warfare with the emperor—Zhang Lu seized his own territory by force when the opportunity arose in 191. At the behest of Liu, Zhang conquered the governor of Hanzhong, but then set up his own Daoist state in the area, rather than submit to Liu’s command.

Here he expanded the movement’s roles, while systematizing their practices into a bureaucracy for local governance. The libationers were made commanders of military units, and senior “great libationers” were simultaneously made military leaders and local administrators of the civilian government.

The Records of the Three Kingdoms (《三国志》), written by historian Chen Shou (陈寿) in the third century, records that “[Zhang] Lu took possession of Hanzhong, taught the Way of the Ghosts to the people, and called himself Lord of the Troops.” Zhang Lu attracted more converts by leaving rice and meat in “responsibility huts (义舍 yìshě),” where travelers or refugees were invited to eat their fill, and join the new state.

Though they were not bent on taking over the empire like the Yellow Turbans, historian Howard S. Levy states that Zhang Lu’s followers “abolished Han imperial institutions, killed official envoys and refused to tolerate the assignment of imperial magistrates to the Han-chung [Hanzhong] area.”

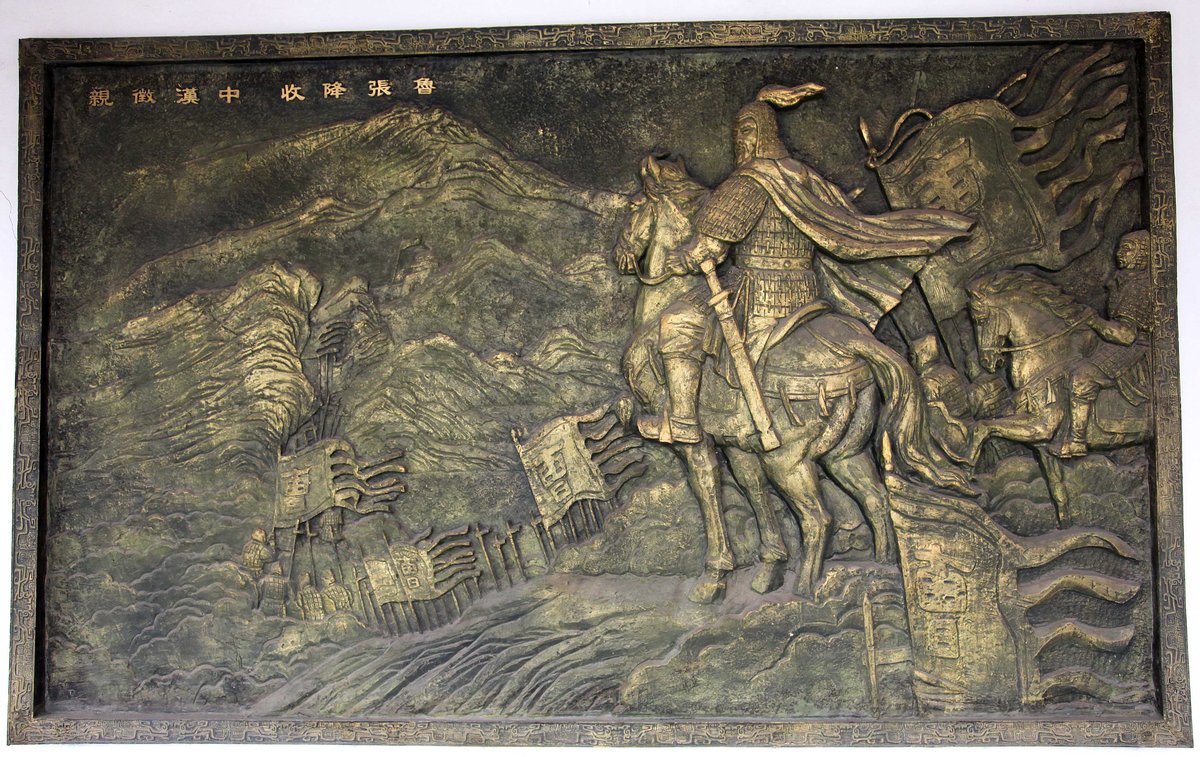

Despite this, Zhang’s state was a relative oasis of calm amidst the chaos as the Han empire came crashing down, until the warlord Cao Cao (曹操) marched on Hanzhong in 215. Zhang surrendered in the face of Cao Cao’s overwhelming military force. For his collaboration, Cao Cao awarded Zhang Lu various titles, and gave him the posthumous title Marquis Yuan when he died in 216.

Though Zhang’s independent state lasted less than 25 years, its legacy lived on. Zhang Lu wrote the Xiang’er (《想尔》), a commentary on the Dao De Jing, which made the text accessible to commoners. The commentary, which stated that a person’s body contained multiple spirits and qi, helped regular folk learn about the Dao (道, the way) themselves.

Likewise, many of the features of Zhang’s state, such as the institutionalized structure, its hierarchical focus that assigned the role of guide to leaders who transmitted the rituals to adherents, and practices such as the curing of illnesses through confession and the exorcism of malevolent spirits, became common features of subsequent Daoist movements. These religious beliefs spread to the north of China when, after the events of 215, members of the Hanzhong community migrated around the country.

The Way of the Celestial Masters did not end with Zhang Lu, and the lineage has passed on to 65 Masters who all claimed direct lineage to Zhang Daoling, though records of the line of descent were murky until the Song dynasty (960 - 1279) and there are still disputes over who the next in line is today.

Even today, the Xiang’er is one of Daoism’s most venerated scriptures and followers continue to practice rituals influenced by the Zhangs’ teachings, for example using special talismans to cure illnesses. Though the violent rebellion of the Yellow Turbans still gets more attention, Zhang Daoling, Zhang Lu, and their independent state established over 2,000 years ago has a legacy that lives on today. The Way of the Celestial Masters represents a crucial phase in the development of Daoism as a fully-fledged religion, expanding Daoism’s reach into wider society and making it accessible to the masses.