Once ridden with air pollution, the northwestern Inner Mongolia city is reinventing itself as a desert-lake tourism destination

Sunshades dot the beach, hiding the crowds of holidaymakers beneath. In front of them, various types of rafts and kayaks are bobbing on the azure water while a caravan of camel-riders marches along the sand. In the backdrop, there are the high-rise buildings, set off by a mountain topped with a huge sculpture of Genghis Khan.

By now, I’ve become fully convinced by the tourism slogan, “To view the sea from the desert, come to Wuhai, China.” I came across it as part of an advertisement for this former coal-mining town in China’s Inner Mongolia region in late September, and quickly booked a trip for my National Day holidays. Seaside and deserts both inspire romantic imaginings that relieve people from realities, making them popular holiday destinations. It’s rare, though, to find the two in one place—and it’s even from an inland city over 500 kilometers away from the nearest Bohai Sea in northern China.

This half-maritime, half-desert landscape—formed by the Wuhai Lake on the Yellow River, which adjoins the Ulan Buh Desert along its western bank—has grown popular in recent years, especially after the 2021 film Wuhai was shot there. It’s “surreal,” said Zhou Ziyang, director of the film, explaining in interviews why he chose a little-known industrial city as the setting of a love story, which ends in tragedy and inspires deep thoughts about human natures and desires.

Long plagued by air pollution from coal mining and coking, Wuhai is now working to rewrite its story. In 2022, the local government launched a cleanup campaign and began promoting the city’s striking desert-lake scenery as part of its new image. Dubbed by some media as “little Dubai in China,” Wuhai quickly became one of the top five niche travel destinations on the Alibaba-affiliated search engine Quark in 2024, boosted by the growing trend of “reverse travel”—avoiding crowded attractions. According to official data, the small city of just 560,000 residents received over 3.6 million visits in the first half of 2024, generating around 4.2 billion yuan in tourism revenue, both up over 40 percent compared with the previous year.

With two days to spare, I try delved into Wuhai’s surreal landscapes as well as real struggles.

Built on coal

Wuhai is a city founded on coal and by migrants only in the last century. According to local media Wuhai News, when the PRC was founded in 1949, the place where the city now sits was home to less than 500 people, who lived mainly by livestock farming and several small coal mines. As more coal was discovered in the region in the 1950s, technicians, workers, and farmers mainly from other northern areas followed to find work in the mines, with 22,000 newcomers arriving in 1958 alone; the trend continued in the following two decades, alongside national campaigns to promote central and western regions’ development.

Explore China’s hidden travel gems:

- 5 Offbeat Holiday Spots to Discover

- When Youth Tourism Meets Village Life in Altay, Xinjiang | Photo Story

- Viral Hinterland: The Famous Chinese County That No One Visits

Wuhai city was officially founded in 1976 by merging the existing Wuda and Haibowan, and taking the first character of their names. It is now the smallest city of Inner Mongolia, but once boasted a coal reserve of approximately 2.5 billion tons. This included more than 60 percent of the region’s explored coking coal, a key material for steelmaking and for smelting bronze and lead, paving the way for it to become a chemical industrial hub.

In the 2010s, after a golden decade of double-digit GDP growth, Wuhai’s economy began to slow as coal reserves dwindled and the country started exploring alternatives to fossil fuels amid rising environmental concerns. In 2011, the city was officially listed as a resource-depleted city by the National Development and Reform Commission, along with two other central government agencies. This prompted Wuhai to pursue economic transformation by upgrading its traditional coal-processing industries while also developing more eco-friendly sectors, such as renewable energy, grape growing and winemaking, and tourism.

Across the water to the sands

Wuhai’s outdoor tourism largely revolves around Wuhai Lake, a reservoir on the Yellow River established in 2013, which naturally becomes my first stop. When I arrive at 9 a.m., the lakeshore is bustling with tents and recreational vehicles. Visitors stroll along the shore, go fishing, feed the gulls, or take boat cruises on the water.

Covering an area of 118 square kilometers, around 18.5 times that of Hangzhou’s famous West Lake, Wuhai Lake is much more of a tourist attraction. “[They] have relieved people here, especially farmers, from ice floods and damages,” my driver, surnamed Yang, tells me. In December 2021, a single ice flood, typically caused by ice blocks jamming the river, submerged five villages, two schools, and more than a dozen factories. Except millions of kilowatt hours’ clean energy from the project, which serves as a dam, sluice, and power station, the lake and surrounding wetlands have changed the deserts’ microclimate, making an optimal stop for over 100,000 migratory birds of more than 60 species on their way to the south in the winter, Nie Wenju, a deputy director of the project, told the Inner Mongolia Daily in 2023.

As instructed by the scenic area’s loudspeaker, I join the queue at the No.1 Wharf to wait for the next shuttle of sightseeing boats to the western bank, or the desert. At the cost of 99 yuan for a round-trip ticket, I embark on a boat with dozens of others after around half-an-hour wait, and step on the opposite bank another 20 minutes later.

Riding a boat to a desert is a novel experience—and even more striking, the closer the boat gets to the sand, the clearer and more azure the water becomes. Such striking contrasts are common here: people in colorful seaside attire stroll alongside those in cowboy hats, leather jackets, and boots. Meanwhile, visitors can enjoy an extraordinary variety of vehicles in one place, from rafts and kayaks on the water, to camels on the sand, and plastic boards and ATVs that let them race up and down the dunes—all available for an additional fee.

Around 2 p.m., I take the return boat and plan to try some local food, but Dianping shows most restaurants are closed for their afternoon break until 5. I settle for lemon tea and roasted gluten at the tourist center, then walk along the Yellow River that flows through the city.

By 4 p.m., the lake near the wharf grows busier, as tourists arrive to catch the sunset or attend evening desert concerts. I skip a second desert trip and call it a day. Unlike Dunhuang’s Mingsha Mountain scenic area, where a ticket allows multiple entries over three days, Wuhai Lake’s 99-yuan boat ticket covers only a single round trip.

A tourist city in the making

It might come as a surprise, but Wuhai boasts a small yet distinctive wine scene. Like other northwestern desert regions of China—such as Ningxia and Gansu, which lie along the Yellow River upstream of Wuhai—the abundant sunlight and large temperature swings between day and night have produced special grape varieties that are high in sugar and well balanced in acidity. Producing over 143,000 tons of wine annually, the city now features four vineyards and more than 30 grape-themed farms, many of which welcome tourists for grape picking, wine tasting, and other hands-on experiences. However, like many of these sparsely populated northwestern cities in China, all these sites are inaccessible by public transport.

Staying at a downtown hotel in this small city, I quickly realized that there were few sightseeing options nearby beyond the Yellow River and Wuhai Lake. The museum scene—often a major draw in more established tourist cities—is, to put it mildly, unremarkable: a wine museum that closed without official notice, and a calligraphy museum with no clear connection to the city’s history.

I opt to visit the Manbala Monastery, roughly 45 kilometers outside the city center, for a deeper look at the region’s spiritual culture. The long drive also offers a chance to glimpse the city along the way.

As we pass a mountain crowned by a giant bust of Genghis Khan—one I had noticed the day before near Wuhai Lake—my driver, Mr. Yang, chats about the controversial attraction. Built over eight years at 600 million yuan, the site includes a museum, though some local officials opposed the project as historically irrelevant. Aside from a legend that the Mongol Empire’s founder once passed through the area during an early-13th-century campaign against the Xixia Empire (in present-day Yinchuan, Ningxia), the city has no clear connection to him. At 89 meters tall—about the height of a 27-story building—the statue is the world’s tallest Genghis Khan monument and draws curious visitors, though reviews on Xiaohongshu (RedNote) are mixed.

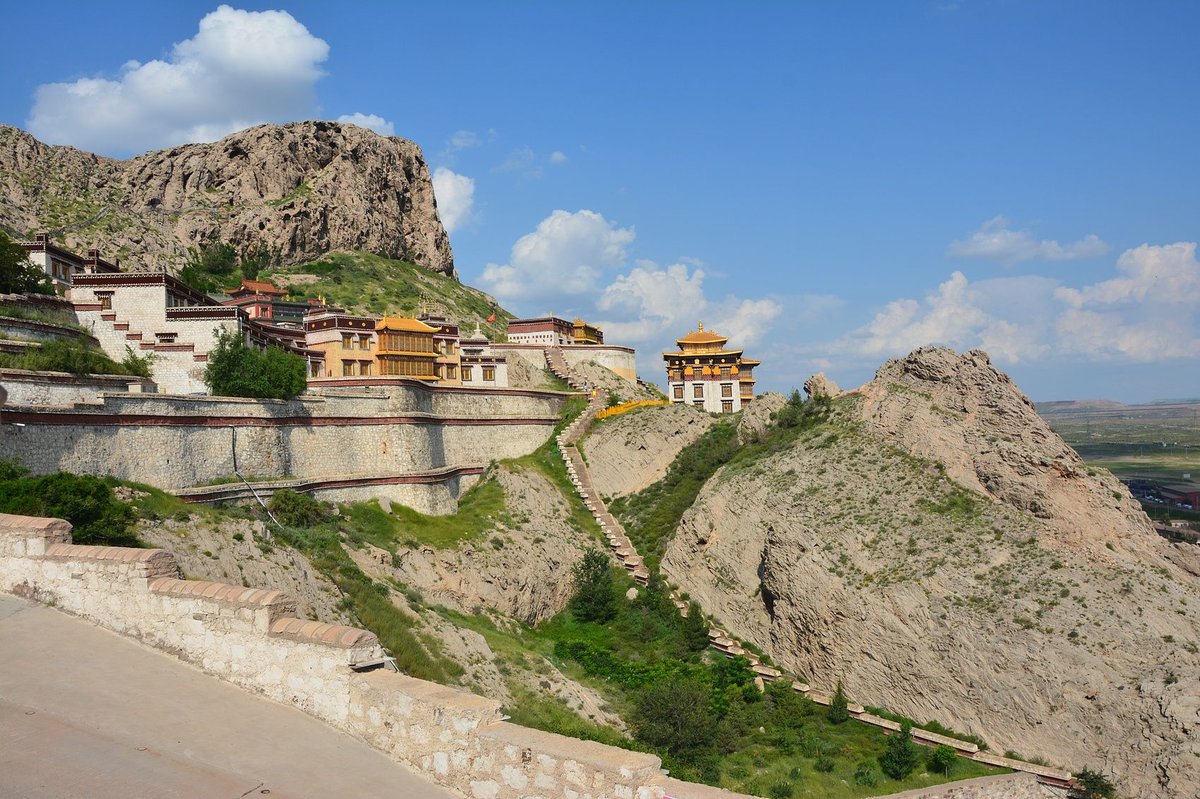

Driving up Tuhai Mountain, we finally reach the Manbala Monastery, perched on a cliff. First established in 1778 and belonging to the Gelug School of Tibetan Buddhism, the monastery is a small complex of gold-roofed white buildings with corridors, courtyards, and a large south-facing terrace. Open to visitors for free, it remains an active religious site and an institute for teaching traditional Mongolian medicine.

Bathed in architectural charm, with traditional Han moon gates, white Tibetan stupas, and sulede (Mongolian ceremonial spears), I turn south to take in the vast openness. White vapor rises like thick clouds from a few cooling towers at a distant power station. Scattered industrial plants across the barren land hint at the city’s deep-rooted industrial past. Emerging from that history, Wuhai is still searching for its identity before it can tell a story to more tourists. Could it be more than just a lake in the desert? With the news that Wuhai’s high-speed railway station was completed at the end of 2025—cutting the train ride from Beijing from 16 hours to seven—I plan to find out on my next visit.