Four migrant workers in Shanghai share their lockdown stories of food shortages and being unable to work

At the time of writing, parts of Shanghai have entered their 15th day under lockdown to contain an outbreak of the highly infectious Covid-19 omicron variant. Residents have been asked to stay within their compounds, public transportation and most businesses have shut down, and food and other supply shortages were reported in China’s biggest city.

Much of the media coverage of the lockdown has focused on urban communities, inhabited by mostly middle class families, as they compete to order vegetables online and make literary memes about the pandemic. But what about Shanghai’s estimated five million migrant workers, many of whom live paycheck to paycheck, are unable to work during the pandemic, and reside in crowded factory dormitories or suburban villages with few resources to handle a sustained lockdown? TWOC spoke to four workers from different areas of China on why they came to Shanghai and how they’ve fared in the last half-month:

Xu Qiangwei, 21, car factory worker in Jiading district

In August of last year, after a 12-hour bus ride from Xinyang, Henan province, I finally arrived in Shanghai. There had been virus outbreaks in many big cities by then, but I chose Shanghai because I heard it was doing a good job in managing the pandemic. I came as soon as I saw a job ad from a labor-contracting firm online.

I dropped out after I graduated from middle school and went on the road with my father, who is a truck driver. I’ve been to Hunan, Hubei, Shanxi, and Yunnan. I have a brother who is two years younger who also dropped out and went to work in Beijing. When I first came to Shanghai, I worked in a makeup factory, making 7,000 yuan a month and paying 500 to 600 in rent. But I quit after two months because I only have a middle school education and couldn’t figure out how to fill out the order forms by hand and back them up on the computer. Last September, I joined this factory, making car parts.

In Shanghai, you can’t really have savings if you only make 7,000 a month. After I subtract rent, cigarettes, clothes, and personal expenses, there’s nothing left. Sometimes I have to pick up part-time jobs at the courier company if I’m broke.

Since the outbreak in early March, several workers have tested positive in the Jiading Industrial Zone where I work. Whenever there is a positive case, our factory would close for three to five days. We would be allowed to return to work only if everyone tests negative. Because of the pandemic, I only worked half a month last month, and haven't been paid yet. I've already spent all my money since this outbreak started.

On March 30, when one of my roommates and I were out doing a part-time job, he was notified by the Center for Disease Control that he had tested positive for Covid-19. He was taken directly to the hospital. Another roommate was also taken away to be quarantined.

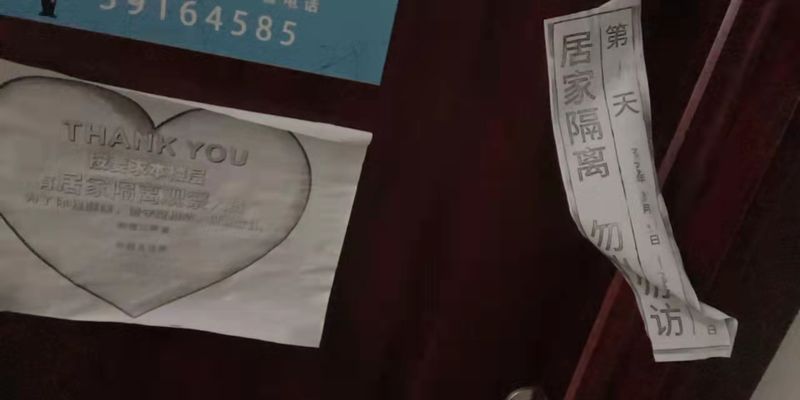

But no one ever took me or my third roommate away. Since then, we’ve been staying in the dorm with a seal taped over our front door. We only bought enough supplies for five days, because the Shanghai government said that the lockdown would end on April 5. I spent that time eating instant noodles. By April 6, I had no food or money left. The price of vegetables and daily necessities had doubled, and the price of takeouts soared to 100 yuan, which I could not afford. I went hungry for two days. I had to ask other workers for a little food. I heard some people say that we’re going to be locked down until May. If that happens, then I'll really starve to death.

There are more than 200 workers in my dorm building. We have never received any government supplies. The company that contracted us didn't give us any help either. The boss only told us to keep waiting.

There is another factory whose canteen is still open. We can go there and buy boxed lunches for 17 yuan during off-peak hours, though by then the dishes are cold. Even so, I can't afford it now. I even tried to volunteer as an epidemic prevention worker, because at least then they’ll feed you, but I couldn’t get in touch with the recruiter.

My family doesn't know about my situation. Frankly, I don't want to tell them, because it wouldn't be of any help. After this outbreak is over, I want to go home. At home, at least I won’t go hungry.

Hu Changgen, 50, security guard in Tangzhen town, Pudong new district

Those who say they will leave Shanghai after the outbreak are just talking out of anger. What are they going to do back home? Starve?

I am originally from Wuhu, Anhui province. I have been living in Shanghai for over 30 years because of the high salary and great job opportunities here. I once did odd jobs, then became a delivery driver, and now I’m a security guard. I make over 5,000 yuan a month, but this means I have to work for the whole month, from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m. every single day. I also need to pay 1,000 yuan for rent in a village in the east of the city. In the past, I used to be able to save 2,000 yuan a month. Maybe young people think this isn’t much, but I live very simply, so it’s enough for me.

On the night of March 27, I read online that Pudong district was going to lock down. We didn’t get any notification either from the sub-district office or our local village council. I rushed to the supermarket, which was very crowded. By the time I finally squeezed inside, there were no more vegetables left, so I just bought two bags of instant noodles. It was too sudden. If we’d gotten the message two or three days earlier, we could have stocked up. Also, several days before the announcement, some people claiming that Shanghai was locking down got arrested by the police for “spreading rumors.” [Editor’s note: The Shanghai Public Security Bureau announced it was investigating two men for this on March 23, though it made no mention of arrests.]

By April 6, I had used up all my gas. After skipping two meals, I borrowed an induction cooker from my neighbor but my pot didn’t fit the burner. So now we have a routine where I give my neighbor some rice and my neighbor cooks it for me. I eat two meals each day: one consisting of instant noodles, and the other consisting of rice. As a side dish, I eat one sausage per day in order to make my supplies last longer. I have half a bottle of fermented bean curd left.

As of April 12, I’ve gotten two deliveries of food supplies, including a crate of milk, a bottle of oil, a bag of bread, a pack of dried noodles, 150 grams of dried mushrooms, 138 grams of dried fungus, and 200 grams of snow fungus, but no green vegetables. On April 9, I received three sausages, and I plan to eat one per day. I tried to buy vegetables online several times but failed. I haven’t heard of any community group-buying around here, but I live in a small village where people aren’t very settled. A few days ago, I had to buy 15 eggs at 40 yuan from Shanghai locals, three times higher than the price before.

See this video on Douyin? [This is] a Shanghai local who can get supplies; they’ve already gotten three deliveries. Look how much there is and how good it is. But us non-locals can’t get much, just snacks and processed food and no vegetables. [Editor’s note: TWOC has found no citywide discriminatory food-distribution policy between locals and non-locals, but there are unverified reports online of some compounds and villages not distributing food to illegal tenants, non-locals, and residents of certain types of apartments.]

All in all, the epidemic has little impact on my life except for having no income this month, so I have to live off my savings. But it’s only temporary, after all. When the lockdown ends, I will go back to work. I still have a favorable view of big cities. In a big city, you can find better jobs, earn a higher income, and live more conveniently. But I hate discrimination against non-locals with all my heart. People like me, even if we work in the city all our lives, could never become locals. If there wasn’t a difference between local and non-local household registration, I could have become a Shanghaier 30 years ago.

Li Long, 26, day laborer in Chedun town, Songjiang district

My name is Li Long. I come from Luoyang, Henan province. Both of my parents are peasants, and I came to Shanghai to make a living because my family is very poor. I arrived on March 10 and have been looking for a job while picking up part-time work to make ends meet. I could make about 150 yuan a day by doing odd jobs such as waiting tables, providing security at events, and making deliveries. I used to drive a digger at a small quarry in my hometown and worked in an electronics factory after graduating from high school.

On March 25, one person in our building showed an abnormal result in a nucleic acid test. The next day, none of us were allowed to leave the building. The door at the end of the hallway was locked from the outside. I live in a four-bedroom apartment with three other families—eight people in total—who work in an electronics factory nearby. I pay 25 yuan per day. We all share one bathroom, which doesn’t have any shower facilities. I usually shower at the public bathhouses, but now I have to boil water to clean myself as best I can because I can’t go out. The epidemic prevention staff told us that [the lockdown] would only last for five days, so I only bought some instant noodles to eat. Who knew the lockdown would still be going on?

I keep telling my parents that everything is fine with me, because they are getting old and I don’t want them to worry. However, I’ve used up all my savings, because I can’t even do odd jobs now. My landlord says it’s okay not to pay him for now since I don’t have any money, but I feel bad about it, because I already owe him 500 yuan. I spend most of my time sleeping or watching movies. I want to get some exercise, but there is not enough space in my room. The volunteers have delivered groceries twice since the lockdown: the first time only a carrot and a potato, and the second time a bag of mantou (steamed buns) and a bag of baozi (stuffed buns). I’ve been relying on the instant noodles over the past half-month, and yesterday some volunteers sent me another box of instant noodles. That’s all the food I have left now. I really hope that we can end the lockdown soon, so I could make some money to support myself and my family.

Liu Zhongzhi, 53, truck driver who transports cargo to Shanghai

I’ve had 32 years of dealings with Shanghai. It’s my second hometown. In 1990, I joined the army. After I retired from the army, I began transporting imported goods from warehouses in Jiangsu province to Shanghai. I earn about 10,000 yuan a month on average.

I am currently in Hai’an city, Nantong, Jiangsu province. In mid-March, I took a shipment to Shanghai. At that time, there were some positive cases in the city, and I thought their epidemic management was relatively lax. I had a hunch that the roads in Shanghai would be closed, so after this trip, I decided to stop working.

As expected, Shanghai closed down on March 28 [Editor’s note: Parts of the city east and south of the Huangpu River were locked down on this date and were expected to reopen on April 1]. Vehicles entering and leaving Shanghai need passes and various formalities. For a small logistics company like us, it’s very difficult to apply for passes. Recently, Nantong has also locked down. We’re all just sitting at home watching our savings dwindle away.

In addition to having passes, people returning to Jiangsu from Shanghai need to isolate for 11 days at home and do three rounds of nucleic acid testing. They want to prevent us from bringing back the virus, like how you wash vegetables several times before you cook them. At the moment, the government has adopted a one-size-fits-all measure allowing no flexibility for logistics workers and vehicles. That’s what you do when you have no better option. Our clients at the foreign trade warehouses also can’t find trucks to take their goods right now. Even when they offer a high fee, we’re afraid to accept the job because of all the paperwork involved in leaving and getting the company’s permission to come back to Jiangsu. I might as well enjoy life at home and improve my cooking skills.

I can’t transport goods, so my income is zero, but I still have to pay for insurance and parking spaces for several vehicles. The year before last, I also stayed home for two months during the outbreak in Wuhan. Driving trucks is tiring and unprofitable. If there is an epidemic, I just rest and recuperate and eat dumplings made by my wife. It‘s better to live a peaceful life. Money is not too important.

After the epidemic, I want to change my career, but I can’t. I don’t want to transport to Shanghai. It’s bitter and tiring, and I have few happy memories of it. The roads are blocked and the people are rude. Some people force the driver to unload the goods without tipping or doing anything to help, but in order to live, I have no choice but to do it. The people in Shanghai are privileged by their location; they can rent out their apartments, play mahjong, and enjoy life. After the pandemic, I hope Shanghai locals can travel to other places and learn about the quality of the people there.

Additional translations by Yang Tingting (杨婷婷) and Iris Xinyi Jiang (姜辛宜). Edited by Hatty Liu.