When World of Warcraft ended in China earlier this year, players lost more than just a computer game

When 18 years of war and adventure came to an end, the final moments were of peace and retrospection. Gathered at the fortified main gate to their capital city, players waved goodbye to a world they would perhaps never visit again:

“Goodbye World of Warcraft! Goodbye, my youth! Goodbye, my friends!”

“Goodbye to all you familiar strangers!”

“May fate reunite us one day!”

Countless similar farewell wishes flickered on the screen, punctuated by automated system messages stoically announcing the inevitable: “server shutdown in 15 seconds, 10, 5…” Then, logout—one last time.

The World of Warcraft journey ended for thousands of Chinese players on January 23, when the licensing agreement between the video game’s US publisher Activision Blizzard and Chinese distributor NetEase expired, nearly two decades after the game first came to China.

At midnight, “when the servers were shutting down and you couldn’t even get to the screen with all your characters anymore; in that moment I did feel a little sad,” says long-time player Hu Jun, a 28-year-old office worker from Beijing, who took no screenshots of his last in-game moments because of the sadness he thought he’d feel if he ever looked at the images again.

Players like Hu didn’t just lose a computer game when World of Warcraft, a massive open-world multiplayer roleplaying game set in an epic fantasy universe, went offline. Hu estimates he had racked up almost 10,000 in-game hours leveling and equipping his main characters, fighting bosses and other players for rare items and achievements, and forging strong social bonds along the way, with some of those memories as treasured as anything in the offline world. With players no longer able to access their Chinese Blizzard accounts, which contain records of their personal histories of war and adventure, many are left with bitterness toward the publisher and a void in their lives, while others are ready to move on.

Hu was “down the hole (入坑),” as Chinese players like to say to emphasize the time-consuming nature of games like World of Warcraft, with the game for well over a decade. He first played the game in 2008, three years after its release in China. “I would watch my cousin play when I was still in middle school,” he tells TWOC. “Around 2010 he stopped playing and gave me his account, that’s when my World of Warcraft journey really started.”

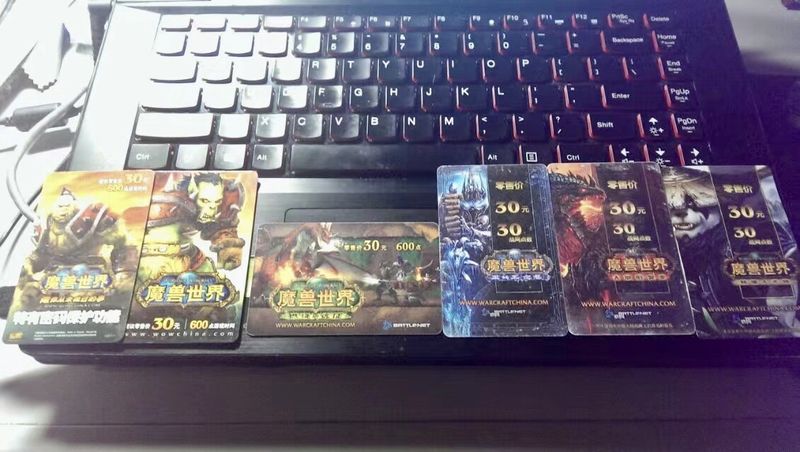

Around that time, some 12 million users worldwide were paying the monthly subscription fee to join a server, create characters, and play the game. Chinese users used to make up a large portion of the game’s player base, with many whiling away the hours in internet cafes on a flexible pay-per-minute scheme available in China. China’s World of Warcraft fandom was especially fierce around 2012 when Blizzard released the Mists of Pandaria expansion, a world inspired by Chinese history and culture full of dragons and other mythical entities, including a new panda-like playable race.

“Mists of Pandaria was when I started going to college, that’s when I was playing like crazy,” Hu recalls.

The expiry of Blizzard’s licensing agreement spelled the end for around half-a-dozen other games, including popular first-person shooter Overwatch, online card game Hearthstone, sci-fi strategy game StarCraft, and fantasy dungeon crawler Diablo. But World of Warcraft’s vast fantasy universe with almost endless possibilities for exploration and strong emphasis on building and advancing unique playable avatars over long periods of time (all linked to one, now inaccessible Blizzard account), is what makes this game’s demise especially heart wrenching, according to Hu and other players. “Each player in World of Warcraft inhabits their own unique world,” as one netizen puts it succinctly on the popular Chinese gaming forum NGA.

Choosing a faction, race, and character to play, then working through missions to gain experience and get up to the maximum level (level 70) in an online world populated by other players, is only the beginning. “We did multiplayer dungeons, we did player-versus-player battlegrounds, we fought other players in the open world with our guild,” Hu tells TWOC, referring to the coalition of players he joined in the game. There are also mini-games to keep players busy, like collecting and fighting pets (reminiscent of Pokemon), and a vast in-game economy based on the many professions players can learn and improve (like blacksmithing or tailoring) to create items for trading or selling in-game.

Even cosmetic items can hold sentimental value. Hu remembers that when he took a stint out of the game around 2008, he returned to find an in-game friend had made a purple shirt for his character to wear. “I kept that very shirt until the servers shut down,” says Hu.

All in-game achievements like killing a final boss or completing a long and arduous chain of missions are recorded account-wide and visible to other players through Blizzard’s achievement system, essentially as a high score not just for Word of Warcraft, but also for other Blizzard games. With Chinese servers shutting down, all this is gone—not deleted, since players were given the chance to secure their account data in a “digital urn” in case servers come online again one day, but inaccessible indefinitely.

It is impossible to say exactly how many daily Chinese World of Warcraft players were left at the end (Blizzard stopped publishing player numbers in 2015) but based on server population stats and other available data, they probably numbered in the low hundreds of thousands, out of an estimated global player count of around 600,000 daily players on average in the last 30 days according to ActivePlayer.io. That’s a far cry from the 1.6 million global daily players on average for Overwatch, but still much more popular than online roleplaying competitors like The Elder Scrolls Online (with an estimated 300,000 daily players on average).

In China, a significant outflux of players may have occurred around 2016 when the Chinese payment model changed from buying game time—30 yuan for 4,000 minutes—to a 75-yuan monthly subscription. The new payment model pushed away many Chinese casual gamers who were used to paying and playing flexibly, for example during their lunch break at an internet cafe. “Once you grow up, become part of society, have a family and job to take care of, you just don’t have the time to play so much anymore,” wrote one Chinese player in a 2018 article published on a Baidu blog analyzing the repercussions of the new subscription scheme. “75 yuan for one month, going online daily but then playing for maybe not even two hours; that just doesn’t pay off.”

The game’s player base may be shrinking, but those who remain are often extremely dedicated. Many have reacted with sadness, bitterness, and frustration now they can no longer access their characters or play the game they worked so hard to progress in. “Of course, there is this feeling of having lost something,” Hu says. “So many memories and experiences...”

Many Chinese players blame Blizzard for their loss. Foreign game publishers need a licensing agreement with a local partner to gain access to and stay in the Chinese gaming market, the second-largest gaming market in the world by revenue. Blizzard still has access to this market via its mobile game Diablo Immortal, which operates under a separate licensing agreement with NetEase and remains accessible in China.

Though the details of the dispute between Blizzard and NetEase that led to the end of their licensing agreement for Blizzard’s PC games remain contested, Chinese netizens appear to mainly blame the US game publisher. Comments on social media suggest they deliberately neglected PC gamers in favor of the more lucrative Chinese mobile game market, which has boomed in recent years.

Committed players can keep playing by creating a new Blizzard account and starting World of Warcraft from scratch on a non-Chinese mainland server. NGA and other online forums abound with guides on how to register a new account, how to buy a Hong Kong phone number for that, how to make a PayPal account to pay the monthly fee (now that Chinese mainland payment methods don’t work), and how to buy “booster” services that keep fast internet connections stable when playing on distant servers in, say, Japan or Korea.

“I just got done making a new account and started playing on an Asian server. Yesterday I hit level 70, and standing in the capital city with other players moving about around me, it feels like I’m back home,” wrote one player on NGA in early March. But not everyone shares this sentiment. “It’s so difficult to get over this feeling of losing everything on the Chinese servers, then you have to start from zero again on an Asian server…finding in-game friends or even just doing your own key quests; doing all this alone is just so tough,” writes another.

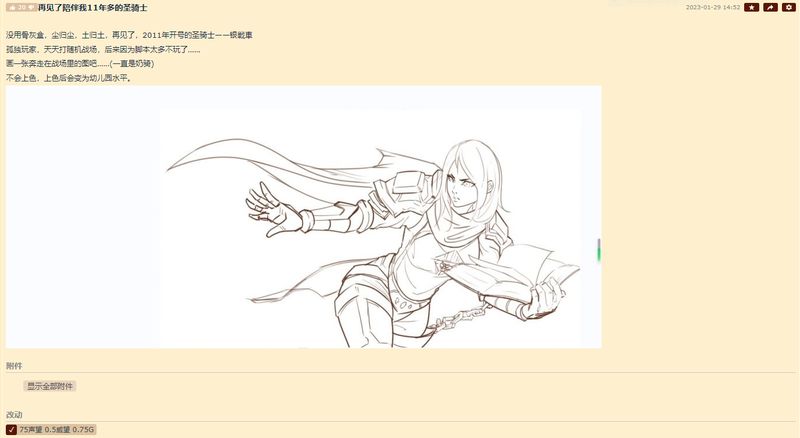

Hu’s journey is probably finished. “If it’s over now, then it’s over, what I cherish most are the memories World of Warcraft gave me, the friends,” he says. But others are still holding out hope that the Chinese servers may come back online again with some sharing (quickly-debunked) rumors that a new licensing agreement is imminent. Some revel in nostalgia, sharing screenshots on NGA of their old in-game characters or videos of their last few moments before server shutdown.

“On the last evening, I had already saved my main character’s progress through the ‘digital urn’ service and then made a [new] small character just so I could say goodbye to my friends and the world. What a pity, that moment felt like the youth I had spent playing this game was coming to an end,” one player born after 2000 who got into the game only five years ago and shared a video of his last in-game moments on Bilibili, tells TWOC.

The uninitiated may wonder why these players can’t just start another game, or find a new hobby, but, as one NGA user writes, after many years of warring, it’s tough to restart from nothing: “So many years spent collecting all that gear, toys...all linked to one account—forget about starting all over again.”