State-sponsored documentary “In Wuhan” stirs debate on the role of media in hard times

The seven-episode documentary series In Wuhan, jointly produced by online streaming platform Bilibili, CCTV, and production studio Figure, has polarized audiences with its portrayal of life at the epicenter of China’s battle against coronavirus since its release for free online streaming on February 26.

Chronicling the sacrifices and stories of delivery workers, volunteer cat feeders, medical staff, neighborhood committees, and chefs cooking up the city’s signature reganmian noodles for charity, In Wuhan states in its synopsis that it seeks to “show the love and pain, gains and losses, melancholy and expectations of ordinary people,” and promises to “warm and inspire” audiences.

However, a sizeable segment of the audience does not want to be warmed nor inspired. In the comments section of IMDB-like movie review website Douban, which hosts over 300 million active users per month, audiences have given the film every rating from one to five stars, leaving the average score a mediocre 6.8.

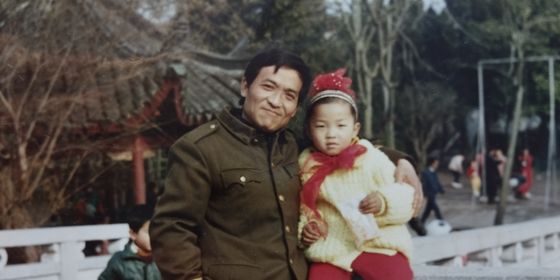

A still frame from “In Wuhan” (2020)

Many viewers are split on ideas of what the role of the media should be during a pandemic, inciting a verbal brouhaha in the Douban comments section of how to understand political documentaries and their relation to the complexities of truth.

The most cynical of Douban users denigrated In Wuhan as damage control for the blunders of the city government in January, during which officials suppressed news of the outbreak and failed to take action until the Spring Festival migration had spread the virus across the country. A Douban user who gave the film a one-star rating wrote, “When the epidemic is over, please don’t be moved, don’t sing praises. Instead, be angry, as performing such tributes only covers up scandal.”

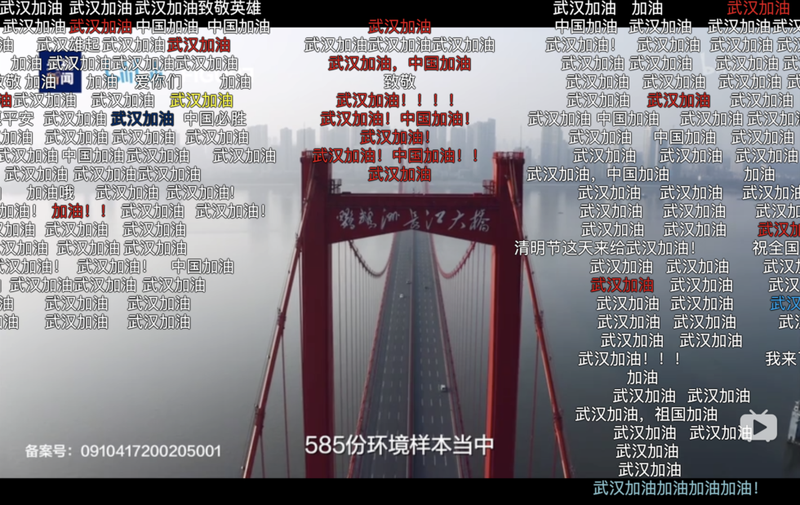

Others debated the merits and elisions of the film’s primary focus on heartwarming stories, palpable in scenes such as when 26-year-old delivery driver Wu You rides his electric scooter over a Wuhan highway bridge at sunset, rushing medicine and groceries to strangers who have asked for help online. The episode’s ending track begins to croon, “The sun will soon be shining on your face.”

A Douban who gave the film three stars lauded its successful dramatization of people’s lives, enough to make “an iron man shed tears,” but concluded, “If you cannot air the darkness, you should at least express the shades of gray… and have some responsibility to society, the masses, and future people to record the truth. Not simply make a promotional film.”

Some skeptical Douban users balked at the “inspiration porn,” hyper-aware that the documentary series aligns with government strategy in which the media’s primary role is to bolster political stability. As Chinese authorities continually regulates TV content in the direction of “social harmony” (for example banning TV shows that are “too entertaining” or contain “foreign elements”), it also prescribes that state media should be mostly uplifting. In a 2013 editorial published in the People’s Daily, party members were implored to use new media to “exert positive energy.”

A still frame from “In Wuhan” (2020)

But is it so bad to feel good? Heroic stories are also a component of reality, and some conclude that frontline workers and volunteers are deserving of public recognition. One netizen dismisses critics of the film as cynical “Douban Youth,” who think “everything is fake” except “CNN, Fox, and The New York Times.” (According to research firm iResearch, over 80 percent of Douban users are under the age of 35, concentrated in cities and coastal regions, and over half of users have a college degree, contributes to this conception of the platform’s elitism).

The film’s director and producer, Zhang Yue, a veteran reporter who cut his teeth at Southern Weekend, explains the series came together not as an order from above, but through personal resolve. When news of the city’s lockdown broke on January 23, he assembled a team of 16 crew members, mostly of the “post-90s” generation, to travel to Wuhan, and he underwrote the millions of RMB invested in the documentary series along with Bilibili.

Zhang also rejects the idea that their production had “special shooting rights” on location, giving the example that when their car’s license to travel in Wuhan expired, he bought an electric scooter and placed the camera in a delivery box, posing as a delivery driver in order to go onto the street and shoot.

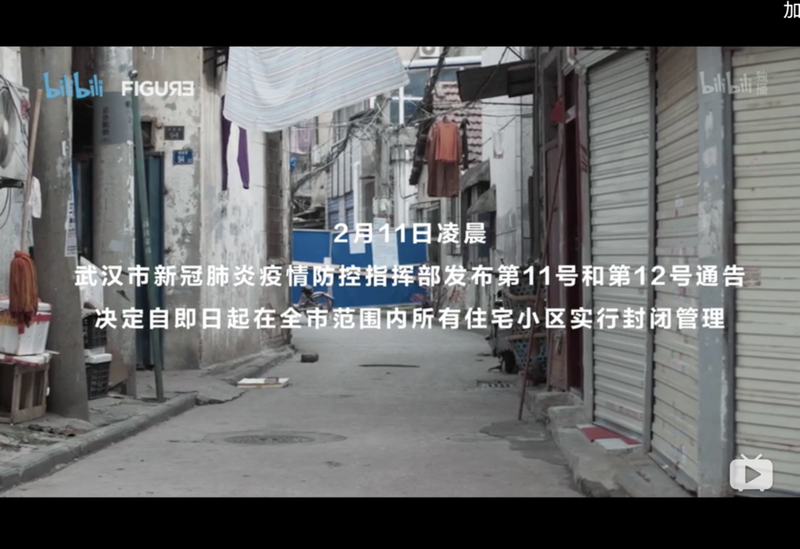

A still frame from “In Wuhan” (2020)

According to Zhang, the series’ fourth episode best represented what he set out to portray. Interestingly, it is also the story that deviates most from formula. The episode, following a decree that all provisions for residents will be group-bought and distributed by the neighborhood committee, begins with utter chaos, as residents complain about the stock that the neighborhood volunteers buy, and seniors balk at having to learn to use a smartphone.

Yet as the weeks wear on, the neighborhood workers turn into a well-oiled system, stocking bags of grain, vegetables, and even chicken. In the moral and emotional climax of the episode, an elderly man hobbles to the tent to ask the committee to buy him gout medicine, and is turned away. As he leaves, 26-year-old neighborhood worker Wang Minye runs out and calls him back, then hops onto an electric bike to the nearest pharmacy. Medicine finally in hand, the senior asks the young man for his name. “It’s not important,” replies Wang.

In the fourth episode, unlike in the others, the subjects being filmed don’t come off as overly conscious of fitting into a narrative, and nobody is trying to be a hero. Residents make the best of a frustrating reality and sometimes lose their cool, while the neighborhood committee grow in compassion as they figure out ways to serve the community’s needs.

A still frame from “In Wuhan” (2020)

Perhaps there’s never been such thing as an objective work of art, let alone a documentary that doesn’t edit—and thus editorialize—reality. For a critically thinking audience that has developed mild allergies to relentless positivity, there are occasional singular moments in Zhang’s film of genuine humanity, sorrow and exultation.

“This is the real Wuhan,” declared Zhang of episode four.

Cover photo of official film poster from Bilibili