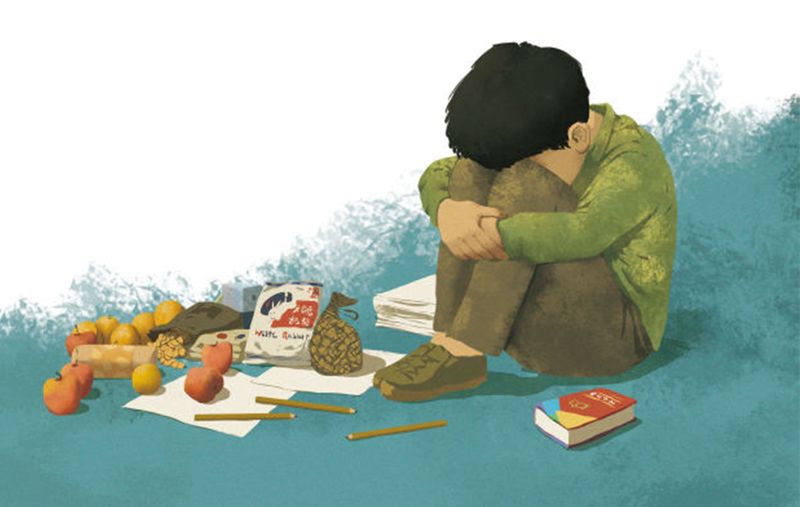

In Shen Shuzhi’s depiction of waning village life, a “left-behind” child comes to terms with loneliness growing up with his grandmother

This is an insignificant village in an insignificant place. A little more than a dozen families live here, perhaps 20 at most. The fields are given over year-round to growing rice and rapeseed. Nobody grows much of anything else. In the winter, after the rice has been harvested, all that remains is the low stubble and the wide, deep marks left behind by the tracks of the harvester. Before the first frost, the stubble wilts and dries out, turning the fields a pale, earthy yellow. Some of the farmers spread the straw on their fields and burn it to fertilize the next spring’s crop. From one corner of these wide open spaces, a faint tendril of smoke begins to rise. The smoke is peaceful.

When the snow falls, the ground is covered in thick and thin bands of snow, but the distant mountains remain indigo. In the summer, the rice in the fields spreads out in a dense sheet a peculiar shade of green that sits at the juncture of blue and yellow. The sun is bright. It shines down on the people who move alone or in pairs through the fields, watering the crops, spreading pesticide, and greeting each other.

When it comes time to eat lunch, the fields are empty. Everyone returns home for their midday meal. Once they have eaten, they spread their bamboo mats on the floor and take a quick nap. The sun rises and burns down on the fields until it takes on the appearance of pale green mist. It’s so peaceful that even the grasshoppers go quiet. The pond is only half full and the sluice gate is kept tightly shut, so no more water can run out. The wind creates gentle ripples across the surface of the water. At that moment, if you stand in your doorway, facing to the west, and look around, shading your eyes against the sun, you will have the sense of a place shrouded in verdant stillness. It is only in the spring, when the air is moist, and new green growth is sprouting, that this place is possessed by a different sort of life.

There was a time when this village was not so desolate. But that was ages ago. There was no way for a kid like Lingfeng to know that. He was only 10 years old. There were only about 10 or so kids of Lingfeng’s age left in the village. In old days in the summertime, they would wash up in the pond together. Walking the dozen or so li to the township school, they would dawdle together, looking for things to amuse themselves with. But once they grew up and left, the village became even more desolate. It was difficult to imagine how that emptiness might eventually be refilled with hope. The young and able went to the city. They filed into the lower classes and worked at the sort of jobs that require only enthusiasm. Only a few young people continued their education.

The people who left the village, no matter their occupation, were referred to by those who remained as having “gone out for work.” It was the elderly who were left behind, along with some of the children. There were very few able-bodied young people left in the village. Even if a few people from a household stayed behind, some of their relatives had to have gone out. Some people went out to earn a living, and some had to remain. The men who stayed in the village drank and smoked. With their farm work on top of that, they aged prematurely: once they hit 50, they started to look much older than their age, with grim faces and hoarse voices.

After the population began to thin, even the planting and harvesting days, which were usually the most lively, became fragmentary. A harvester, borrowed from the county government, could harvest all the rice in a single week. The machine tore up the straw and spat it out. There was no longer any straw to pile up, feed to the cattle, or burn in the fields in winter. Since the harvester replaced the sickle, there was no need for the rice to be transplanted into neat lines. Seeds could be scattered haphazardly and the seedlings tossed into the field. There were no more straight lines of seedlings, and the days of whole families helping out with spring planting were gone. Only in the few low places that the harvester couldn’t reach would people still bend down to plant seedlings individually. Those had to be harvested with a sickle, as they always had.

On spring mornings, there were no longer children rubbing their eyes and stumbling sleepily out of bed to take the family cow down the dewy ridges between paddy fields. With tractors to do the work, there was no need for cows. There was no need to take them down to the pond on summer nights. There was no need to house them in barns all winter—and there was no rice straw to feed them. Nobody had to whip a cow around a paddy field for plowing. And so, most of the village cattle ended up hanging from a hook in a butcher’s stall. Once the cows were gone, the grass along the paddy ridges began to grow up all together at an alarming rate. Even on the busiest roads through the village, the sagewood grew more than a meter tall on both sides.

The few children left in the village have stopped dawdling on the road to school. They’ve stopped looking for things to eat or play with to pass the time. TV is more interesting. And on their vacations, they usually go to stay in the city, and, if their parents earn enough, take a few classes. The elementary school in the village used to have five grades, but then it was cut back to three, and a short time after that, it became two grades. Finally, there were not enough kids for even a single class, so the kids had to go to the school in the township. The old school remained, behind a stand of fir and bamboo, a low wall, and thick weeds, up a slope at the entrance to the village. In the summer, cloaked in luxuriant green, it would be hard for anyone to tell that it had been a school. The village was not only desolate, but had begun to take on the air of an abandoned place.

All of this remained beyond Lingfeng’s comprehension. He was only in the third grade. Every morning before six, he stood with the other children at the dike at the entrance to the village. They waited together on the concrete bridge for the van that would take them to school. Lingfeng had lived with his grandmother since he was little and his parents had “gone out for work.” He only saw them when the New Year came and during summer vacation. He was used to it. It didn’t occur to him that it was possible to have a close relationship with one’s parents. He just naturally developed a bond with Grandma and her oldest son—his uncle.

Even if he didn’t share much with Lingfeng, Uncle knew how the village had been in the past. When he was young, he used to take a hen cage down to the pond and catch fish. Lingfeng could not have imagined how life had once been. Uncle had grown up in the village, and now he was growing old there. He had been left behind to watch over the place. His wife and daughters were in Nanjing. He would see them a few times a year when he made the trip into the city, carting plastic canvas bags of vegetables and chickens. He would spend a few days there, or sometimes even a month, but he always returned. He brought with him candy and soda for Lingfeng, as well as books and pencils bought by his daughters. They asked him to move to the city. The family could be together, and he would be able to find a job much less backbreaking than working on the farm. He turned them down, though. He had a single reason for staying behind: if he left, there would be nobody to look after his mother and his nephew. They needed someone to watch over them.

A few dozen meters from the front door of Lingfeng’s house were the paddy fields that had been divided up between each resident of the village. Further still was the triangular pond, lined with leaning willow trees. The house had been passed down by Lingfeng’s grandfather. There were three rooms with tile roofs, but the family spent most of their time in the kitchen and the bedroom adjoining it. The kitchen was large, with a stove against one wall, a cupboard, and a counter with a cutting board. Against the back wall was a hen cage. Up in the eaves, Lingfeng’s grandmother—his Nainai—had placed the dark red coffin she’d had a carpenter build for her on her 70th birthday. It had been up there for a decade, collecting a thick layer of dust and cobwebs.

A wooden door led from the kitchen into an adjoining room. The walls, painted with lime however many years before, had tarnished to a dark yellow, and the plaster was starting to come off in chunks. Here and there were crooked Chinese characters written by children with sticks of charcoal. The characters were left by Lingfeng’s older cousins, who had by now all gone out to work or attend university. Two beds were placed tightly together in the center of the room. Newspapers from decades before were taped up to the heads of the beds. Over the years, the sheets of newsprint had yellowed until they were the same color as the tape that held them in place. Across from the bed was an old four-legged wardrobe wrapped in cedar veneer. Its drawers overflowed with ancient and recent possessions. A television set rested on a lower shelf. Beside the television, there was a rice cooker. Near the large window, there was a low dining table with two benches set around it. A recliner faced the television. Apart from high summer, there was always a thin padded jacket laid over it.

Nainai was already over 80, but she still took care of all the washing and cooking. Her eyesight was still good. When she had free time, she liked to walk the couple of li to the village down the river to play cards with her relatives. Sometimes she even came back with a few yuan in winnings. Her hearing was getting worse, though, and talking to her required shouting. There were times when she fell ill and the doctor from the village up the river had to be sent for. After being on a drip for a few days, she would usually recover her spirits. And life went on.

It was the 15th day of the first lunar month of the year, and the semester had already begun for third grade students. The sun began to glow a bit warmer. Soft new growth appeared in every corner of the village. Lingfeng took the van home from school and arrived at the village around five in the afternoon. He took his homework out of his bag and went to work at the dining table. His writing was wild and cramped. It leaned to one side so severely that it looked as if it might slip right off the page. However, there was nobody around to notice or to tell him not to hold his pen that way, so he kept at it. Arriving at questions he could not answer, there was nobody around to ask, so he left them blank. None of this caused him any distress. In the kitchen, Nainai sat in front of the stove, feeding it with fuel. She fried green cabbage and garlic scapes, fresh from the garden. Uncle usually joined them, but he had gone to the dike to drink that day.

On the table, positioned close to the window, was a jug of boiled water. Beside it was a ceramic cup with Nainai’s leftover tea. The inside of the cup was lacquered with a thin layer of tea leaf glaze. When his homework was done, Lingfeng put his notebooks and textbooks beside the recliner. He grabbed the cup and guzzled cold tea.

Nainai, crouched in front of the stove, scolded, “Don’t drink cold tea. You’ll get sick! That cup doesn’t have a lid on it. It might’ve gotten bugs in it!”

“Who cares!” Lingfeng said. His voice was loud and his tone a bit sharp, but Nainai didn’t hear a word.

“Wash up and eat your dinner!” Nainai said. Lingfeng reached into the basin with a gourd ladle and rinsed his hands. That was good enough for him.

“Use some soap,” Nainai said. “Look at those hands of yours! If a turtle caught you, he’d think you stole his claws.” She chuckled to herself. She meant that his hands were so dirty that they reminded her of a turtle’s muddy webbed feet. Lingfeng accepted the order, refilled the basin with half a ladle of water, put in some soap, and gave his hands another rinse. Nainai was pleased. Looking at his dripping hands, she said, “Much cleaner, right? They even look a bit whiter.”

After he washed his hands, Nainai brought the green cabbage and garlic scapes to the table, as well as a bit of salty meat steamed in the rice cooker. The pork glistened, golden and oily. As he ate his rice, Lingfeng couldn’t help himself from going back to the meat again and again. Nainai frowned. “Stop eating so much meat,” she said. “You’re fat enough already!”

Nainai rarely ate meat. Her generation had a bit of faith in the Buddha. Even if they didn’t burn incense or recite sutras, they tended to stay away from meat. Nainai’s teeth had long ago been replaced with dentures, anyway. She was more concerned about Lingfeng’s sudden weight gain. It wasn’t his fault. He had always been a sturdy boy. He ate like a little pig, too. He wasn’t picky about food. But after a trip to Shanghai to see his father, he had returned looking different. He seemed to have become plump and dark-complexioned during his time away. Before he left, his clothes had already started to become small on him, and when he got back from Shanghai, they looked ready to burst.

Nainai was always happy whenever anyone asked about her grandson. Although she had raised more than a dozen grandkids, Lingfeng was her favorite. Lingfeng’s father, her youngest son, had been her favorite child. During the first 10 years of his life, Lingfeng had rarely left her side. It had meant a lot more work for her, but also a measure of lively comfort. She still remembered the early winter morning 10 years prior, just before the New Year, when Lingfeng had come into the world with a clear, loud wail. She never much cared for her daughter-in-law, but at that moment, she was so elated she could hardly wait for the day to dawn so she could rush out to the village and proclaim, “My Blackie has himself a Little Blackie now!” Blackie was her nickname for her youngest son. Three days after his birth, when everyone gathered to toast the child, he was given the name Lingfeng. Uncle came up with it.

Nainai loved watching TV, so Lingfeng’s uncle had bought her a 200 yuan satellite dish to hang outside the gate. The TV received all sorts of programs, even some from abroad. Occasionally, foreigners with white headdresses speaking a language no one understood would flash up on the screen, before someone changed the channel. Most of the houses in the village had satellite dishes like hers. After dinner, she washed the dirty dishes in the pot with the water from rinsing the rice, then she washed her face, and went to watch TV.

She often felt dizzy, so she tied a blue cloth band around her forehead. It gave her a slightly eerie appearance. She liked watching opera. The local township station often played the local style of Huangmei opera, and she would watch any productions that they aired. She didn’t understand all of it, but she could usually guess at the general narrative. It didn’t deter her, anyway. The TV was always turned up extremely loud. It was loud enough for anyone passing by outside to hear clearly. Lingfeng was used to it. The volume didn’t bother him. He only occasionally commandeered the remote. A little before nine, he fell asleep on his bed. Nainai went on watching. “Ai ya,” she said after a while, “it’s getting late. Lingfeng, you’d better get to bed.” She turned to see that Lingfeng was already in bed. “Good boy.” She looked at the time on the TV. “Nine already! No wonder my head is pounding. Time for bed.” She switched off the TV. The room was dark. The three toon trees in the garden cast their shadows across the plastic sheets over the windows.

Lingfeng’s mother was a tall, slim woman, with a head of thick, dark curls. This was rare for a woman from the countryside. She had a face that was instantly charming, with a smile that revealed straight, pearly white teeth. Unlike most country girls, she had a nice-sounding name: Qiuzhong. One thing that must be said about her is that she was once married to a man who lived nearby. If you turned south from Nainai’s house, you’d be at her first husband’s family’s home. Nainai’s youngest son was friends with Qiuzhong’s first husband before she re-married and became Nainai’s daughter-in-law. One summer day, Qiuzhong drank a bottle of pesticide. Luckily, she was quickly discovered and carted off to the township clinic. They pumped her stomach and she returned home. After that, she divorced her husband. Nainai could not quite understand what had happened. She left behind a five-year-old son named Dalong. Then she made the short trip to Nainai’s home and married her youngest son.

That family history was the reason that Nainai did not like her daughter-in-law. A year later, however, Lingfeng came into the world. Nainai loved her grandson dearly. A short time later, her son went out to work in Shanghai. His enthusiasm for being a father transformed his formerly slack attitude to one of firm determination. This determination was colored also by new, warm dreams for the future.

Lingfeng’s mother stayed at home with her mother-in-law to look after the boy. Nainai complained privately about her daughter-in-law’s laziness, but she did nothing to get between mother and son. Back then, Nainai was in better health, and she took care of all the cooking and cleaning for the household, and still worked in the garden and raised chickens. Even though she complained about her daughter-in-law being lazy, Lingfeng’s mother did take care of some things by herself—having a child by its very nature meant there was always lots to do—and a year after giving birth, she went to work in Shanghai. It was hard to say whether she wanted to make money for her family, or if she had grown tired of staying in the village. Every now and then, Lingfeng went to stay with them in Shanghai, but he spent most of his time at home. So, Lingfeng grew up with Nainai in the village house with concrete floors and high eaves, watched over by his grandfather’s portrait on the wall.

Little by little, Lingfeng started to take after his father. His complexion darkened, and his eyes were large and dark, framed by bushy eyebrows. He grew tall and strong. The only difference was that he didn’t have the same mischievous twinkle in his eye that his father did. To put it more accurately, despite being the most beloved son of the family, Lingfeng never gave in to arrogance. He never intentionally tried to cultivate honesty and sincerity, but had simply been born with it. He spoke slowly, so he sometimes gave people the impression that he was slightly dazed. As sedate and taciturn as he was, he still liked playing with the other kids in the village. That was what kids in the village did—it was all they knew: how to play. Lingfeng often snuck out of the house to join them. On his father’s side of the family, his youngest cousin was already 10 years older than him, so he didn’t have many kids his own age to play with. He was forced to play with village kids who were three or four years older than him. When they teased him, he never ran back home to tell on them. They played hide-and-seek, tramped through the mud, splashed in the water, tossed playing cards, built slingshots, made fish hooks, and busied themselves with any other diversions that they could think of.

When Lingfeng was little, his Nainai would watch over him closely. She was scared that he would run into trouble if she let him out of her sight. She was particularly worried about the many irrigation ponds in the village. People in the village would often hear Nainai’s tuneless voice calling his name. She would be standing in the doorway, toying with a piece of bamboo ripped off the broom. She would never actually have hit Lingfeng with the makeshift switch, but she wanted to scare him, so that he wouldn’t risk getting close to the ponds. When Lingfeng’s aunt was around, she would harrumph and say, “He’s your little treasure.” This was because Nainai didn’t like the fact that her eldest son’s wife had given the family only granddaughters.

Many times, Lingfeng would not answer Nainai’s call, so she would have to wander down the road until she found him. Once his Nainai found him, he dropped whatever he was playing with and obediently followed her home. This made people think he was a bit slow. He heard his grandmother’s voice but seemed reluctant to answer. When adults heard her call and saw him playing by the side of the water, they would say: “Lingfeng, Nainai’s calling you. You didn’t hear? Hurry home before she gets worried!”

“Oh,” he would say, and then stand up, call out to Nainai, and rush home.

Dalong, Lingfeng’s half-brother, had a name that meant “big dragon,” and it matched his temperament: since the time he was a baby, he had been a bundle of energy. He was older and taller than Lingfeng, and he had a wild streak. He was known to climb up trees to snatch bird’s nests, paddle around in the pond, and steal melons from neighbors’ gardens. He carried on in a loud voice and often got into fights. He put everything he had into whatever he did. Even his handwriting showed these same tendencies: the characters were big and blocky, stacked up like marionettes that struggled to stand. Dalong’s father had a temper. He was in Shanghai, too. So, Dalong, like Lingfeng, grew up with his grandfather, Yeye, and his great-grandmother, Taitai. Yeye was in his fifties and had asthma. He breathed like a pair of bellows and went around with his back bent. Taitai was Yeye’s mother. She was blind in one eye. The good eye was always red and she would weep whenever the wind blew. She sometimes sat behind her bed curtain and counted her money, rolling out each bill from the fold, then rolling it up again. When she was done, she stuffed the money back under her pillow.

Once Lingfeng started sneaking out, Dalong took up the tasks of an older sibling, and taught him to play in the mud. They went together to dig up black mud from the side of the dike and slam it on the cement floor at the front of the house. Lingfeng called him Gege—older brother—and, as long as Lingfeng’s father wasn’t there, their mother might call them in together for dinner. Except for Nainai, everyone at the table was happy. When New Year came, they went to play at their shared maternal grandmother’s house in another town, and stayed a few nights before coming home.

There were, however, disruptions to everyday life. By the age of five or six, even though Lingfeng was not aware of what it meant, his mother came back less and less each year. Lingfeng was not brought to Shanghai as often, either. When his parents were together, they bickered more often. On the third day of the New Year, they left behind a few hundred yuan more than required for Lingfeng’s school fees, then returned to the city, leaving Nainai and Uncle to look after everything else.

Finally, the announcement came: They were going to divorce. What did it mean? It meant that her mother was no longer part of the family. “Your father and mother no longer live together,” Nainai told him. “Your mother said that your father wasn’t good to her. Your mother is a nasty woman!” Nainai knew that her son and his wife had given the court “irreconcilable differences” as the reason for the split, and this is how she explained things to Lingfeng. Fortunately for Lingfeng, Nainai was only concerned about him. Since the court gave custody to his father, she had no worry that his mother would come to steal him away from her.

Lingfeng had hazy dreams. In his waking hours, he started losing games to his classmates. He could not understand his teacher’s questions. He was overwhelmed and would break out in a sweat. Sometimes he dreamed that his parents were together again. He dreamed that he was back in Shanghai on summer vacation, sitting in their tidy room, eating Kentucky Chicken, or whatever it was called.

At five in the morning, Nainai awoke from a light sleep and shouted for Lingfeng. She did not bother looking at the time. She was worried only that he would be late. “Lingfeng! Get out of bed and go to school!” There was no trace of defiance or arrogance in the boy. He sat up, emerging from his dreams, rubbing his eyes. Within a minute, the dreams were forgotten. Nainai fetched the basin, so he could wash his face. She pressed some money into his hand. “Buy something to eat when you get to school,” she said. “And don’t waste it on snacks.” This was money her sons, daughters, grandsons, and granddaughters had gifted her for the new year.

“Alright,” Lingfeng said, “I got it.” He went out the door. It was not yet fully light outside.

The driver who took the kids the 10 li to school charged each family 200 yuan. The van was originally intended to seat six, but he kitted it out with benches, so more than 10 kids could sit in the back. There were no traffic lights in the village. The road to the school was wide. The trip took around 10 minutes. The driver made the trip several times a day, ferrying students to and from school. The first trip was just after six in the morning. He started from Shanju and picked up students along the roadside the whole way down to the township.

Lingfeng was usually the first to arrive at the bridge over the dike. The sun was still low in the sky. The late March air was damp and cold. The rapeseed was in bloom and the golden petals, heavy with dew, dropped to the ground and stuck there, creating a patch of yellow. Below the rapeseed blossoms, the foxtail brushes, too, were dripping wet. Lingfeng did his best to kill time. He took one of the foxtails and beat the rapeseed blossoms to knock the water off of them. Within half an hour, a few more students came up the road, calling his name. He shouted back to them. The woman who got up early to wash rags in the pond was visible in the distance.

Because of his height, Lingfeng sat in the back row at school. His grades in math were okay, but his Chinese homework was always full of mistakes. His teacher was a fat, middle-aged woman. She tried to work with him, but it didn’t seem to do any good. She knew that nobody in his family cared about his schoolwork. He had nobody to ask for help. It was better to keep silent and not cause problems. He was a strong boy, but he was well behaved. There were more than 60 students in the class. It was hard for her to manage them, and she did not have any time to guide a student one-on-one. Unless the homework was done extremely poorly, there was nothing to do but mark it with a red check.

Whenever the teacher called on Lingfeng, he took a long time to come up with his answers, and he spoke in a low voice. His classmates started to look down on him. They thought he was stupid. So, he was ripe for bullying. Whenever there were unpleasant chores to be done, they passed them off on Lingfeng. At the end of the day, he was often the target of teasing. Nobody took it too far, though, since they didn’t want to get him angry. He was a strong boy, after all, and they were a bit scared of him. Despite how they treated him, he persisted in his good-hearted dullness, and grew up to be a tough, dark-complexioned boy.

The autumn that Lingfeng turned 8 years old, he got a phone call from his father. Rather than waiting for the New Year, he planned to return to the village early. Lingfeng jumped for joy. His father said, “I’ll bring you lots of candy, Lingfeng, and I’m going to bring you a new mother, too, and a little sister. She’ll call you ‘big brother.’ Are you excited?”

Lingfeng thought for a moment. “I’m excited,” he said. His father was satisfied with the answer and hung up the phone.

Nainai did not openly betray any concern, but she was a bit nervous. The next day at dinner, she told Uncle about the special call. “I don’t know,” she said, “but I heard someone say she’s way better than Qiuzhong—a hard worker, tidy... They’ve met her, and that’s what they say.” Uncle was aware that Nainai was pleading the case for her youngest son. But, even though she had not met her, she was not particularly happy with the idea of a new daughter-in-law. Uncle was a bit confused by his brother’s behavior. He had not made a fuss about him dumping Lingfeng on their mother, and he didn’t want to get involved with this affair.

“Don’t worry about it, alright?” he said.

Nainai didn’t say anything else. She smiled placatingly, then ate the rest of her meal in silence.

When winter came, Lingfeng’s father arrived with his new mother. Lingfeng made sure to call her “mom,” just as his father had told him. The new mother had bleached blond hair, and she was shorter and fatter than his real mother. She seemed to be a bit older, too. When she heard Lingfeng’s name come up in conversation with Nainai or Uncle or Lingfeng’s father, she smiled. When she was alone with Lingfeng, she made it clear that she was to be respected. He was too young to fully understand what this meant. She had three daughters from a previous marriage. Lingfeng’s half-sister was her fourth child. Naturally, none of this was told to other people in the village. The little girl wore a thick jacket embroidered with red flowers. Two yellow pigtails were pressed in place against her head by a pair of barrettes with red flowers on them. Lingfeng was unspeakably happy. He raced around the village with her, his mouth stuffed full of candy, showing her everything.

A few days later, the candy and melon seeds nearly exhausted, Lingfeng’s father left, taking his wife and daughter with him. Lingfeng reached into his pockets each day to finger the dwindling supply of hard candies. He remembered Nainai’s advice: “Take your time eating that candy.”

In the final week of April, the fragrance of the flowers gradually subsided, and golden herbs grew at the side of the pond. The seedlings had already been planted in the fields. After a light rain, they began to stretch their delicate roots into the soil. The days grew longer. When Lingfeng rushed out at six in the evening each day to play, the sun was still in the sky. His play time grew longer. Sometimes when he got back, Nainai had not returned from playing cards. He stretched out on the table and did his homework. One day, when he had finished two or three pages, he decided to go out and play cards with Xiao Leilei. Uncle came in from outside, carrying a wicker scoop and an empty bag of fertilizer. When he saw that Lingfeng was trying to bolt, he shouted, “Where are you off to? Did you get your homework done?”

“I’m finished,” Lingfeng said meekly. He stood to attention beside the table.

Uncle opened the book and began to inspect it. Although he only had a few years’ education, he could see that Lingfeng’s work was a mess.

“Why do you write like that?” he asked. “This isn’t good. When you’re in class, you need to be listening. If there’s something you don’t understand, you need to ask your teacher. Okay? No matter how smart a person is, they can’t figure out everything by themselves. They have to ask. You got it?”

“Yeah,” Lingfeng said. He had no idea what Uncle was talking about.

“Uncle’s going to Nanjing on the first of May. Is there anything you want me to bring back for you? I’ll tell your cousin to buy it for you and I’ll bring it back.”

Lingfeng thought for a moment. “Uncle,” he said, “I want a Xinhua Dictionary. My Chinese teacher told us we need it.” The village had a tiny Xinhua Bookstore, but Lingfeng had never been inside.

Uncle confirmed with Lingfeng that all he wanted was the dictionary. “Okay,” he said, “I’ll get her to buy it for you. I’ll bring it with me when I come back.”

The night before he was to leave, Uncle picked some vegetables from the garden and put them in a plastic canvas bag. They filled half of the large bag. In the morning, he held back a fat hen and a rooster when he let the other chickens out. He tied their feet with red nylon cord and stuffed them in a sack. He was worried they would suffocate on the way there, so he told Lingfeng to use a pair of scissors to make some holes in the bag. He saw Uncle off to the edge of the village, where he got into the same van that Lingfeng usually took to school.

Seven days later, Uncle returned home in the same van. He arrayed on the table some lollipops, White Rabbit candy, fried dough twists, sponge cake, dried longan, apples and tangerines, loose leaf paper, pencils, a pencil sharpener, and a Xinhua Dictionary. Longfeng flipped open the cover and saw that his cousin had written his full name on the first page in black ink in her beautiful handwriting: “Shi Lingfeng.”

When the rice was harvested and dried that fall, Uncle piled it up in the corner of his room. When that was done, he went to Nanjing again. This time, he did not hurry back after a month. He took his daughters’ advice and got a job as a night watchman at an internet cafe. Before he left, he gave Grandma Yang in the village a few hundred yuan to look after Nainai in case she got sick and none of her kids could get back in time to look after her.

The day he left, Nainai stayed in her room, wiping away her tears. The day was just like any other, but that night, there would only be Lingfeng and Nainai at the dinner table. After a while, people started showing up in the middle of the night to steal fish from Uncle’s pond. They eventually came in broad daylight. Nainai shook with fury, but there wasn’t much she could do about it. The next spring, Nainai and Lingfeng were left to work the garden alone. Nainai brought out a stool and sat on the ridge between the fields, pulling weeds. Lingfeng worked behind her, turning up the soil with a short shovel. Before the sun set, the seeds and seedlings were in the ground, ready for spring to start.

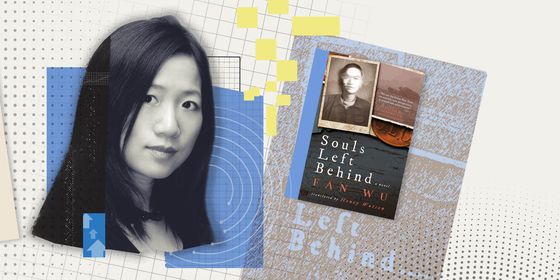

Author’s Note: The draft of this story was finished years ago, so it was not exactly a look at “days past” back then. I revised it twice over the next few years since then, but didn’t really pay much attention to it. Nearly a decade later, I came across the old draft by chance and could not let it go this time. Though it was pretty raw, since I had just started studying writing then, the story is a pure dream full of sorrow. So, I decided to try revising the whole piece, hoping to make it a more mature story. Nearly two decades on, the children of that past have all grown up and left, while the elders have passed away. The generation in the middle has now returned to the village to face their own aging condition in a much more withered countryside. Those spring days are now indeed long past.