From ankle crushing to slow slicing, ancient Chinese punishments and torture were brutal

September 1630 was not a good month for Yuan Chonghuan (袁崇焕). The Ming dynasty (1368 – 1644) general’s military reputation lay ruined after he failed to fight off an invading Jurchen army at Shanhai Pass in today’s Hebei province. Next, he was accused of collaborating with the enemy. Though there was little evidence against him, the Ming state hastily found Yuan guilty and sentenced him to the most brutal of punishments: death by lingchi (凌迟), or “slow slicing.”

In front of a large crowd at Ganshiqiao in Beijing, an executioner began slowly cutting and slicing Yuan’s body with a knife, removing various body parts while keeping him alive. It took half a day for Yuan to die, after receiving hundreds of cuts. According to Northern Affairs of the Late Ming (《明季北略》), written by Ming historian Ji Liuqi (计六奇), local residents collected Yuan’s body parts after he finally stopped breathing—they hated him so much they wanted to eat his flesh.

Lingchi was reserved only for heinous crimes such as high treason, multiple homicides, or killing one’s master. However, there were many other forms of physical torture once used either as punishment or to obtain confessions in ancient China.

As early as in the Xia dynasty (c.2070 – 1600 BCE), physical punishment was vital to sustaining political rule. The Book of Han (《汉书》), a historical text finished in the Eastern Han dynasty (25 – 220), stated that Yu the Great (大禹), the mythical founder of the Xia dynasty, “imposed corporal penalties because people’s virtue have deteriorated.”

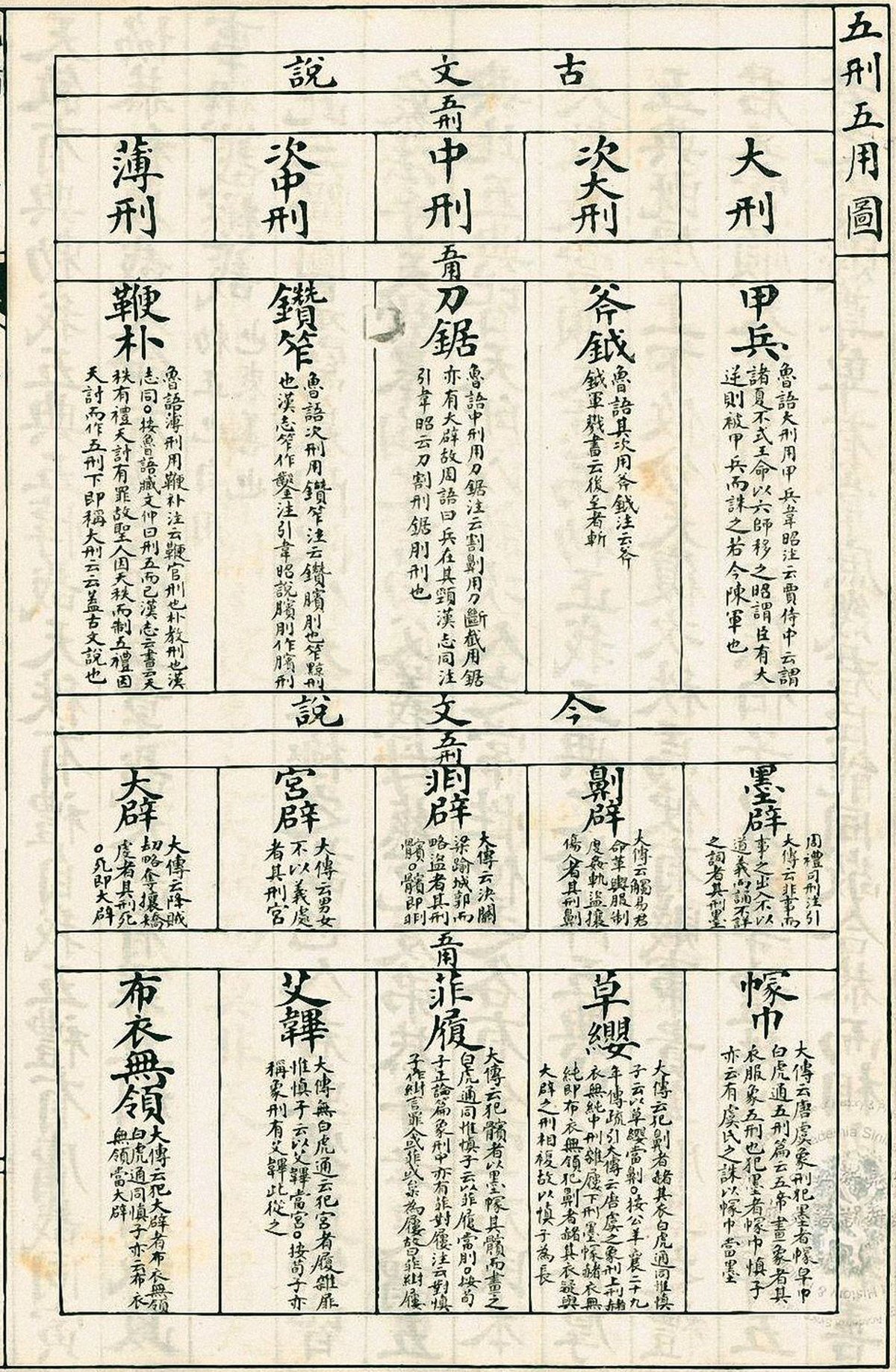

From the Xia to the Qin dynasty (221 – 206 BCE), physical punishment was institutionalized as the “five punishments (五刑).” They included: tattooing the face or forehead (墨), cutting off the nose (劓) , amputating the feet (剕), removing reproductive organs (宫), and death (大辟).

Read more:

- Strangest Laws from Ancient China

- Could You Pass an Ancient Chinese Driving Exam?

- The Strangest Deaths of Ancient Chinese Rulers

According to the Rites of Zhou (《周礼》), a work on Zhou dynasty politics and culture, there were 500 crimes punishable by each of the five punishments. For example, anyone who disobeyed an order from the emperor, committed rape, dabbled in theft, or caused bodily harm would have their nose cut off. Those who illegally used the emperor’s carriage would have their feet removed.

There were also many colorful and cruel methods of execution. A criminal could be boiled alive, beheaded and have their head displayed in public afterwards, or even dragged by chariots at speed until their head and limbs were torn off.

Shang Yang (商鞅), a famous politician of the Qin State during the Warring States period (475 – 221 BCE), whose policies helped unify China under Qin rule, eventually died from the chariot method. According to Strategies of the Warring States (《战国策》), a collection of stories and histories of the period compiled during the Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE), Shang Yang was accused of rebellion and tried to go into hiding. He was thwarted by one of his own policies, however: guests had to present identification to stay at inns, so none would offer a room to Shang Yang, who was trying to travel incognito. After he was finally caught, Shang Yang was fastened to five chariots and promptly torn to bits.

One of the most terrible penalties was 俱五刑, literally meaning “all five punishments,” though these were different penalties to the 五刑 mentioned above. The Book of Han explained the details: “Tattoo the face, cut off the nose, amputate both feet, beat with a stick until death. Cut off the head and then throw the body to the public.”

Li Si (李斯), prime minister during the Qin dynasty, suffered this fate after being framed for treason. Court eunuch Zhao Gao (赵高) had Li tortured until he admitted to the crime. In 208 BCE, Li was subjected to all five punishments before also being cut in half at the waist.

Later, Emperor Wen of the Han dynasty made reforms to some of these punishments, allegedly after being persuaded by the daughter of a prominent doctor who was sentenced to suffer one of the five punishments.

Chunyu Tiying (淳于缇萦) was the daughter of Chunyu Yi (淳于意), a famous doctor who faced punishment for allegedly failing to properly diagnose a noblewoman’s illness, resulting in her death. Chunyu Yi was arrested without a proper investigation and faced one of the five punishments. Tiying followed her father to the capital, where she appealed to the emperor, pointing out the cruelty of the punishments and volunteering to become a court slave for the rest of her life in exchange for her father’s release. Moved by Tiying’s devotion, the emperor pardoned Chunyu Yi and issued an edict to abolish the five punishments. But the emperor brought in flogging, penal servitude, and cutting off one’s hair (an unfilial and shameful act in Confucian culture) as alternative forms of retribution.

In the Sui (581 – 618) and Tang dynasties (618 – 907), a new system of punishment (also made up of five penalties) was established that included: beating on the buttocks with a bamboo cane (笞), beating on the back, buttocks, or legs with a large stick (杖), compulsory penal servitude (徒), exile to a remote region (流), and death (死). The death penalty came in two main forms: hanging and decapitation.

Though the most vicious corporal punishments were no longer used on convicted criminals, similar techniques were still used to extort confessions. The notorious “Embroidered Uniform Guard (锦衣卫),” the secret imperial police of the Ming dynasty, was widely known for inquisition by torture. The ankle crusher, a device of wooden planks connected with rope, was one of their favorite tools. The secret police would force the suspect’s legs between the planks and then pull on the rope at both ends so the wooden boards squeezed tight against the suspect’s feet and legs. The torture would often result in broken ankles. A similar tool was the finger squeezer, consisting of five sticks with a rope connecting them. The suspects’ fingers would be put in between the sticks and the rope pulled tight to crush them.

Sometimes, they could be more creative: “Red Embroidered Shoes” were iron shoes heated over flames until red hot and then forced onto the suspect’s feet.

The Qing dynasty (1616 – 1911) saw more fundamental changes to corporal punishment (though torture continued). By the mid-1600s, the five penalties from the Sui and Tang were abolished, and only flogging was left as an official physical punishment for crimes, alongside the death penalty for serious violations.

Then in 1904, Emperor Guangxu announced that flogging with a cane and stick would also be outlawed. The next year slow slicing was finally officially abolished…just 275 years too late for poor Yuan Chonghuan.