Stories of two post-Covid homecomings to mourn loved ones and sweep the tombs on Qingming Festival

“I told your dad this morning that you’re coming home,” my mom says as she rushes to help carry my luggage out of the train station. But when I arrive at our house on the outskirts of Ningbo, my dad is not waiting at the door to greet me as usual.

After a 20-hour journey from the Netherlands to Zhejiang province—my first trip back to China since 2021—I am home for Qingming (“Tomb-Sweeping”) Festival to commemorate the first anniversary of my father’s death.

On April 17, 2022, I woke up in my apartment in Amsterdam to countless missed calls and voice messages on WeChat. “At 3 a.m. your dad was coughing. I poured him some hot tea and he said he felt better. At 5:30 I woke up again to find he had passed away already,” my mom sobbed down the phone. “I didn’t know when he left us.” At 67 years old, my dad had died unexpectedly in his sleep.

I was working in the Netherlands, and China’s Covid-related travel restrictions made it almost impossible for me to return home for the funeral. Shanghai was under lockdown, so I couldn’t fly back via that city as usual. China also required all overseas arrivals to undergo 14 days of centralized quarantine—by the time I got out, I would have missed the funeral anyway.

Instead, I tried burning incense in Amsterdam, as a person’s spirit is said to awaken after death and follow the scent home. “Don’t make your dad’s soul travel so far to find his daughter,” my mom chastised me. My cousin had a more modern suggestion: He wanted to livestream the funeral so I could attend from afar. “Why make your cousin so sad?” my aunt questioned him. She didn’t want to upset me with the ceremony, so I didn’t attend the funeral, digitally or otherwise.

In my family, Qingming Festival is not just about death and tomb-sweeping; it’s a chance to reunite and enjoy the arrival of spring together. The festival fell on April 5 this year, but our preparations began the day before. While my mom was out buying chrysanthemums, fruits, and other things we would be taking to my dad‘s grave, I chatted with Kyle Paul McMahon, a 33-year-old English Literature teacher in Chengdu, Sichuan province.

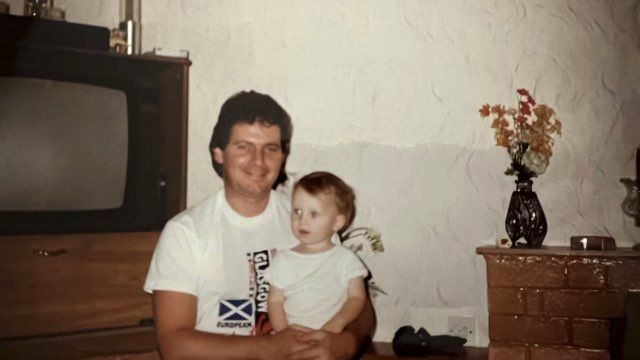

Our stories are like two sides of a mirror. “I wanted to show him this part of the world he had never been to,” Kyle says about his father’s planned trip to Chengdu once Covid restrictions ended. But on March 24, 2022, his dad passed away in his home in Scotland. Kyle couldn‘t travel back for the funeral, so he came up with his own way of commemorating his father’s passing: a giant tattoo of a wild thistle on his chest—the emblem of Scotland.

Kyle has many vivid memories of his dad. He would take him to soccer games as a boy and treat him to comfort food after a tough match. Kyle also says his father made “the best rib sauce in the world” and owned a massive collection of over 10,000 DVDs, many of them old gangster movies. “Ribs and movies tonight?” his father would often ask him on weekends.

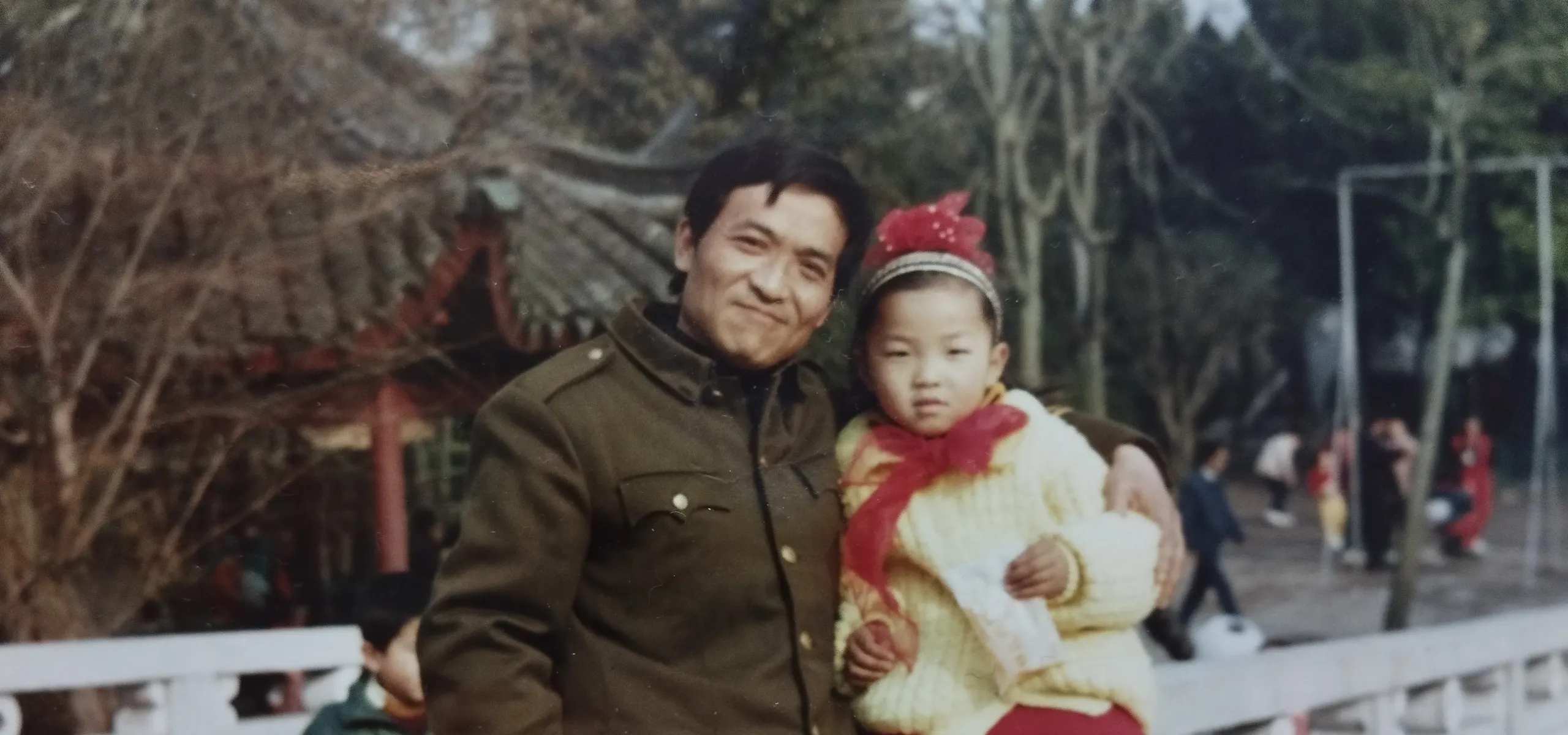

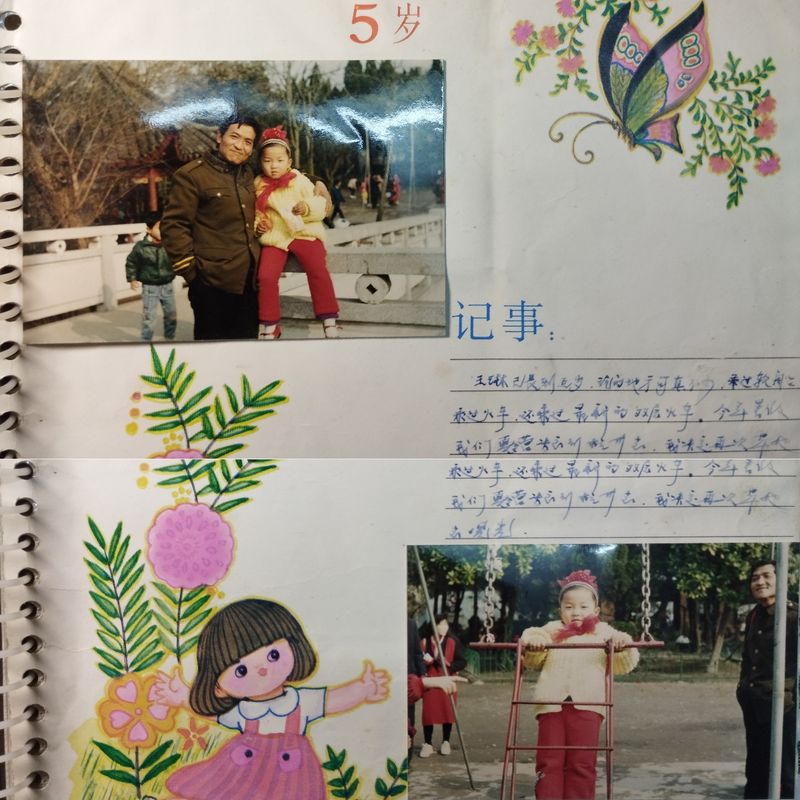

I had a routine with my dad too. Every Sunday morning, he took me to eat wontons and visit the children’s bookstore because he wanted me to read as much as possible. ”You loved to draw and make up stories, Dad decorated our home with your paintings and shared the stories with everyone,” Mom recalls about my childhood.

My last interaction with Dad was through a video call during my lunch break on April 15, 2022. “Eat well and don’t try to save money,” he said, and repeated his usual advice about not sending money home and enjoying my life abroad. Then he retreated to the background and let my mom do the rest of the talking. When she urged me to lose some weight, he jumped in: “No need. She‘s looking good in that blue shirt today.”

As Kyle sends me photos he took with his dad, I start to feel guilty. I flip through all my own albums and find only a few old photos showing me together with my dad. After I grew up and went abroad, I took many selfies on my travels but forgot to take photos with my father.

Kyle says he will travel back to Scotland next week for a gathering to remember his dad’s life. Bagpipes will play at the get-together, as his dad loved the sound. I have something more practical for my dad in mind—making paper yuanbao (元宝), silver ingots that symbolize money, for him to spend in the underworld.

On a rainy afternoon the day before Qingming, I have several bags to fill with yuanbao. I put two fingers behind the flat paper, press it, and it expands into a full bowl-shaped ingot resembling the real thing that was used as currency in ancient China.

“What did dad do in his younger days?” I ask Mom while we fold the paper. “He worked in the park nearby in the 1980s; he did all sorts of things. He guided tourists around the park and temple, made buns in the canteen, and projected films,” she says, reminiscing about how he would set up screens in the park reception hall or even outside. “Watching films in the forest was very romantic.”

“How did Dad court you?” I try to dig up the untold story of how my parents got together. “One day your father took his niece to the kindergarten and saw me working there,” my mom tells me. She was the principal of a local kindergarten back then. “He wrote little notes and asked the kids to pass them to me. The notes said things like ‘meet at 7 tonight at the intersection,’ but I always trashed them.

“Once on a stormy evening, I suddenly remembered the notes and asked your uncle to take a look at the intersection. To our surprise, he was standing there like a fool. My brother gave him an umbrella, and I was told off by your grandparents for being so heartless.

“After that, your dad started slipping into our office unannounced. Whenever we tried to chase him away, he gave an innocent smile and said ‘I just came in to read newspapers.’

“Your dad was persistent as sticky candy for three years. Not everyone has this kind of courage,” Mom says. “That’s because there were no dating apps for Dad to use then,” I reply jokingly. I still marvel at my dad’s silent perseverance.

Our trip down memory lane makes the repetitive yuanbao folding a fun experience. When mom seals the bag of yuanbao, she folds the top into the shape of two horns. “It means the next generations of the family will stand out from the crowd, just like growing horns on the head,” she says.

We finally head to the cemetery around 11:30 p.m.—the holiday traffic will be worse the next day. On the way to the mountain where my father’s ashes are buried, the rain suddenly stops. “Your dad is lucky,” Mom says, “otherwise everything would get wet.” She has brought bags stuffed with fruits, cakes, and qingtuan (青团), green dumplings made with glutinous rice usually eaten during this holiday.

It‘s a quiet walk up the mountain in the dark, but despite the tombs dotted all over, there is no spooky feeling. Everything smells fresh after the rain, and the route is lined with stalls selling fresh chrysanthemums even at this hour. The mood is light and friendly. “You look like a miner,” I tease my cousin, who is lighting the way with a headlamp. When we finally reach my father’s tombstone, we place several chrysanthemums next to it to let him know that we’ve arrived and that we miss him.

The gray marble tombstone is cool after the rain, and I lean against it, as if hugging dad and warming him up. Before we burn all the yuanbao and their bags for my dad, we also burn some yuanbao in the areas around his tomb. This is called jieyuan (结缘, making good contacts): By sharing the yuanbao with my dad’s neighbors in the surrounding tombs, we hope he will have good relations with them in the afterlife.

In front of Dad’s tomb is a marble table and several stone stools. Mom lays out five classic Qingming dishes on the table: kaofu (wheat gluten), tofu, yellow bean sprouts, soy-braised pork, and yellow croaker, all signifying prosperity, while I pour yellow wine and scoop rice into bowls.

It’s a midnight feast, with candles and incense. We must bring all of these offerings at Qingming for three consecutive years: “For the first three years, Dad is a newcomer in the underworld. If he has good wine and dishes to treat others with, he can make new friends,” Mom says.

I pour several rounds of wine, as if Dad and his guests were finishing the bottle. “Have a good meal and make friends,” I pray secretly while my family members chat and indulge in memories.

Kyle and his dad suddenly come into my mind. Kyle told me he will bring flowers and photos to his dad’s grave next week, but no food or wine. I suggested bringing some old gangster movie DVDs for his dad to enjoy with new friends in the underworld. He finds it a funny but touching idea.

It seems the Qingming Festival connects people from all over the world, both dead and alive.