With a record number of people taking the Chinese bar exam this year, attention has turned once again to the country’s toughest exam—and to how it has evolved from selecting imperial officials to fostering public legal awareness today

This March, Liu Zheng, a security guard at Peking University, achieved a dream that once seemed impossible. After a decade of auditing law courses during the day and patrolling the campus at night, the 33-year-old finally became a practicing lawyer in Beijing.

Liu’s journey has been no easy feat. During the 10 years, he took the legal professional qualification exam, or fakao (法考), six times before finally passing in 2021. Often hailed as the toughest exam in China for its low pass rate and overall difficulty, the fakao has become even more competitive in recent years, with nearly 1 million students sitting for it this year.

Unlike in countries such as the US and Japan, where only law school graduates are eligible, China’s system is more flexible. Before 2018, anyone with a bachelor’s degree or higher could qualify; since then, candidates must have either formal legal training or relevant work experience.

However, the Chinese bar is no less demanding than the US. The current test, held once a year, consists of two parts: an objective exam in September with over 100 multiple-choice questions covering subjects like Chinese legal history, followed by a written test in October. Only those who pass the first stage can advance to the second, with scores usually released on November 30.

The exam itself has become a benchmark for modern legal qualifications, standing between aspiring judges and lawyers in training. Yet its influence extends far beyond the courtroom, with online prep courses and annual exam questions making headlines and fostering broader public awareness of the rule of law.

Read more about the development of law in China

- The Rocky History of China’s Marriage Law Reforms

- Strangest Laws from Ancient China

- Is China Finally Moving Toward Smoke-Free Public Places?

Early roots

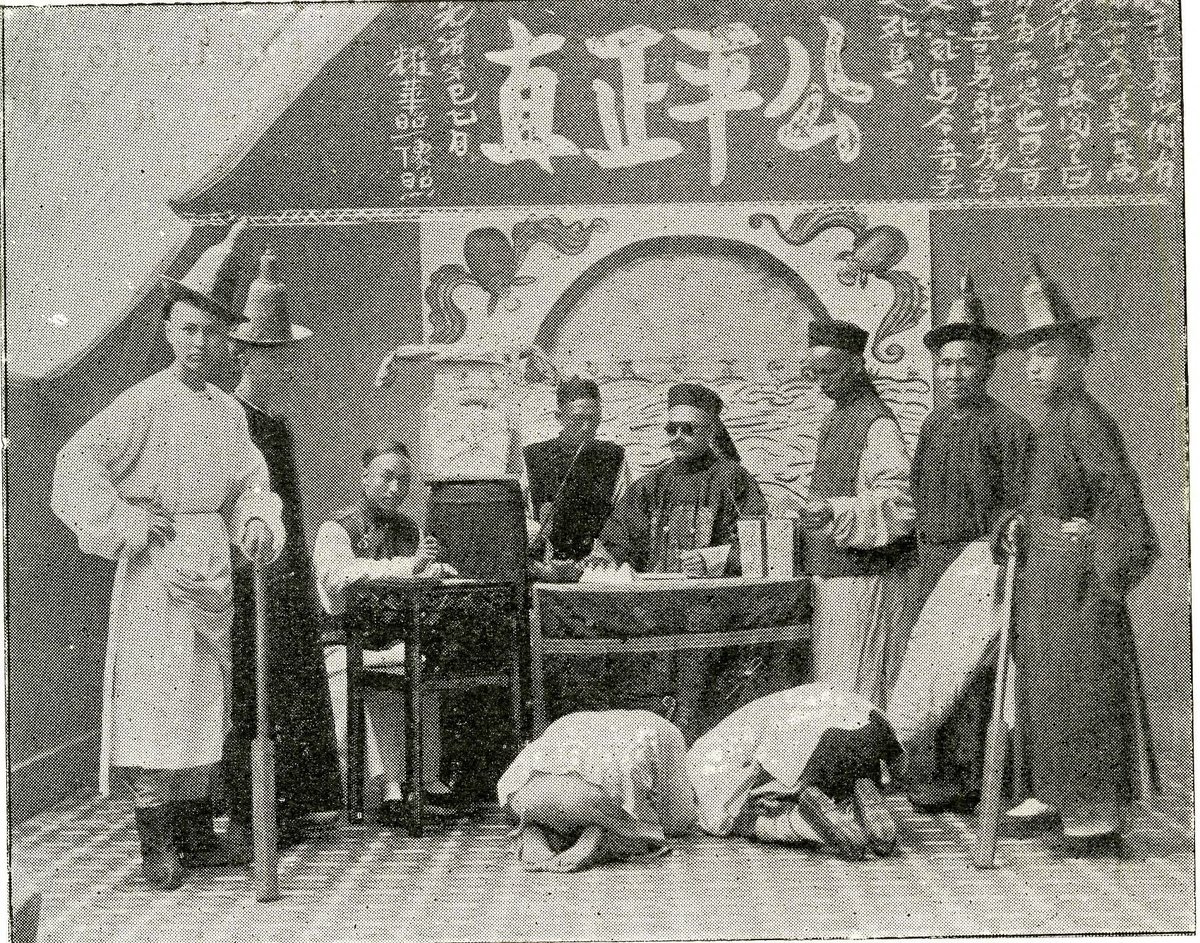

Although the modern fakao has only existed in its current state for a few decades, its intellectual roots stretch back millennia. During the Qin dynasty (221 – 206 BCE), the concept of governing through law began to flourish, and candidates for court service were evaluated on their understanding of legal principles and administrative governance. This tradition deepened during the Tang dynasty (618 – 907), when mingfa (明法), or “understanding the law,” became an essential part of imperial examinations. At that time, candidates were tested on their knowledge of written laws, practical judgment, and ability to reason through hypothetical cases.

By the Song dynasty (960 – 1279), examinees were required to apply laws to specific cases—a precursor to today’s case analysis. Beyond academic exercise, these legal assessments also reflected ancient China’s evolving philosophy of rule by law, as observed in the Warring States period (475 – 221 BCE) philosophical essay Guanzi(《管子》): “The law is the standard of the world and the model for all affairs.”

From reform to modernization

China’s modern legal examination system dates back to the early 20th century, when reformers like Shen Jiaben (沈家本) sought to modernize the empire’s legal system. As Vice Minister of Justice, Shen, inspired by the Western legal system, led reforms that abolished centuries-old forms of torture such as lingchi (凌迟) or “slow slicing,” separated civil and criminal law, and established China’s first government-run law school in 1906 to cultivate legal professionals. With its Western-style curriculum and rigorous testing, the Imperial Law School in Beijing, where Shen played a direct administrative role, trained around 1,000 graduates to serve in local governments across the country, laying the foundation for modern legal education in China.

In 1910, recognizing the uneven qualifications of court judges, the Qing government organized China’s first nationwide judicial exam, making it a prerequisite for judicial service.

During the Republican era (1912 – 1949), as the legal profession expanded across China’s treaty ports, the government introduced regulations for lawyers in 1912, allowing candidates to qualify through exams or assessments. That same year, the government held its first national lawyer exam, issuing certificates to the 297 people who passed. However, constant warfare and political upheaval during this period disrupted legal education and examinations, making it impossible to build a stable system for training legal professionals.

The profession faced further setbacks following the founding of the People’s Republic of China. In the early 1950s, lawyers were banned from practicing, labeled remnants of the “old society,” and criticized for “speaking for the evil” by defending criminals. For nearly three decades, few defense lawyers existed in China’s courtrooms. It wasn’t until 1979, amid the restoration of the Ministry of Justice, that the lawyer system was reinstated. That year, the Shanghai High People’s Court held its first public defense hearing in a case involving a fugitive who had impersonated others and disrupted social order.

In 1986, Minister of Justice Zou Yu told state newspaper People’s Daily that lawyers made up just 0.002 percent of China’s population—far from enough to meet the country’s growing legal needs. Zou called for expanding the legal workforce and improving its quality. With few industry standards at the time, the newly introduced national lawyer qualification exam became a crucial step toward professionalization. That year, over 15,000 practicing lawyers across China participated in the first national lawyer qualification exam, which covered 10 subjects, including jurisprudence, constitutional law, criminal law, and legal practice.

In the late 1990s, China’s rapid economic growth fueled an unprecedented demand for legal professionals. A 1998 People’s Daily article noted that lawyers in Shanghai were in high demand, drawing interest from people of diverse fields, including economics, foreign trade, and foreign language. Many law firms began recruiting directly from universities through campus partnerships. In 1999, over 180,000 people registered for the national lawyer qualification exam, a 61 percent rise from 1995. Law schools also surged in popularity, with Peking University’s law faculty attracting the highest-scoring liberal arts students nationwide for several consecutive years.

Judges, however, faced murkier waters, as the country lacked unified regulations for their qualification before 1995, leading to uneven training and skill sets. Judges could be civil servants, university graduates, or even someone with no formal training. This mix left the judiciary with inconsistent standards and chaos. In 1999, Yao Xiaohong, deputy director of Jiangxian County Court in Shanxi province, was charged with corruption, illegal detention, and wrongful convictions. The public was outraged to learn that Yao had not even completed elementary school and called for reform of the legal profession.

As a result, China’s Supreme People’s Court, Supreme People’s Procuratorate, and Ministry of Justice announced the unification of exams for all legal professionals in 2001. The following year, more than 360,000 people, including judges, prosecutors, and lawyers, sat for the first unified National Judicial Examination.

The exam soon gained a fearsome reputation. With a passing rate of merely 10 percent, it became known as a grueling “hell-mode” challenge that trapped many candidates in years of arduous study and repeated failure.

In 2018, the system was replaced by today’s fakao, formally known as the National Unified Legal Professional Qualification Examination, which shifted focus from academic theory to practical legal issues. The new exam also expanded eligibility to include arbitrators and civil servants engaged in administrative review, law enforcement, and government legal affairs.

Unlike its predecessor, questions and answers to the fakao remain strictly confidential. Prior to 2018, the Ministry of Justice routinely published official answers online and even opened a section on its website for public discussion of disputed questions. But since the reform, the ministry no longer releases such materials, citing the possibility of reusing test questions in later years. In 2019, a candidate surnamed Li even sued the ministry for withholding the answers, but the court dismissed the case, ruling that they were protected as state examination secrets.

Beyond the exam

Today, passing the fakao remains a ticket to prestige and success, and is often glamorized in TV dramas and reality shows that play on the high pay and social status of legal professionals. Yet, behind the scenes, the reality is less promising. With more than 830,000 practicing lawyers nationwide—about 5.8 for every 10,000 people—the market for legal representation is crowded. Many young law graduates face low pay, long hours, and limited opportunities, especially in smaller cities. In 2020, the pressures of the profession made headlines when a Beijing lawyer in his 20s took his own life after being dismissed for mistakes he made at work. In addition, a report from IFeng Weekly last March highlighted that at a law firm in Guizhou province, only half of the lawyers were able to make ends meet, earning less than 2,000 yuan for cases that previously brought in 10,000 yuan.

But this hasn’t stopped people from taking the exam. In 2024, over 960,000 hopefuls registered for the exam—a growth of 12 percent year on year. The popularity of the fakao has also given rise to a booming tutoring industry worth an estimated 1.8 billion yuan in 2023. Unlike K-12 education, China’s legal exam training industry relies heavily on its “star teacher” culture, with institutions leaning on high-profile instructors to draw students.

More than a professional gateway, the exam has also fostered public legal literacy. Luo Xiang, professor at China University of Political Science and Law and one of China’s best-known fakao instructors, went viral in 2020 for turning dense legal jargon into humorous anecdotes that he’d post online. Most viewers aren’t watching to prepare for the notoriously tough bar exam, but for entertainment.

For his 32 million-plus followers of all ages on the streaming platform Bilibili, Luo brings Chinese law to life through real-life cases involving everything from school cyberbullying to hidden cameras in shared rentals. “The law can often feel obscure and distant from everyday life, but Luo makes it feel deeply connected to our daily lives,” wrote one viewer.

In one popular video exploring the line between self-defense and excessive force, Luo recounted a controversial 1980s case in which a woman pushed a would-be rapist into a cesspool where he drowned after she repeatedly stopped him from climbing out. The court ultimately ruled that the woman acted in legitimate self-defense and bore no criminal responsibility. “If I were the woman, I’d step on him four times and smash him in the head with a brick,” Luo joked, sparking tens of thousands of comments under the video.

“Beyond individual ambition, the exam also plays another vital role—legal education and public awareness,” Lin Min, professor from the China University of Political Science and Law, told Southern Weekly in 2020, commenting on Luo’s popularity. “If [professors like Luo] can plant the right ideas in people’s minds and hearts, the influence and value would extend far beyond the classroom.”

From the imperial halls of the Tang dynasty to modern testing centers across China, the pursuit of legal talent has always reflected the nation’s evolving ideals of governance and justice. For candidates like Liu, the security guard-turned-lawyer, the fakao is just the first step into a career in the esteemed profession, yet it also represents a centuries-long effort to define the scope of the law and foster greater public awareness of rights and responsibilities.