Mental health services and families struggle to understand, recognize, and treat rising teen depression

Yu Nian couldn’t remember how many times she had told her mother that she wanted to end her life, only to hear her mom respond, “I think you’re just bored.”

Having suffered from verbal bullying by a classmate for years, Yu, then aged 12, went to see a doctor alone in 2019 after she started hurting herself on her hands, legs, and other parts of her body. She was diagnosed with depressive tendencies, but tried and failed many times to get her mother and her school counselor to take her diagnosis seriously.

For the other 30 million adolescents under the age of 17 in the throes of depression in China today, it’s a similar uphill battle to seek help due to the stigma attached to mental illness, concerns about their privacy, and the lack of mental health awareness among adults who are apt to dismiss their symptoms as being the normal signs of puberty or mood swings.

According to the National Health Commission, this mental health crisis among Chinese teens is mainly caused by school bullying, intense academic pressure, and family trauma such as corporal punishment or a lack of a close relationship with one’s parents. The crisis is also underreported. A 2021 report from the Institute of Psychology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences estimated that 24.6 percent of about 30,000 children aged between 10 and 19 surveyed across the nation had noticeable depressive symptoms, and the prevalence rate grows with age. However, national broadcaster CCTV noted in 2021 that less than 20 percent of people of all ages with mental illness have sought clinical help.

For the teens affected, the consequences can be deadly. This January, 15-year-old high school student Hu Xinyu, whose disappearance from his dormitory last October led to a three-month police search that dominated headlines nationwide, was found dead a few hundred meters from school near a voice recorder where he documented his wish to end his life due to academic pressure and trouble fitting in at school. In January of last year, 17-year-old Liu Xuezhou, whose search for his biological parents was widely followed by Chinese netizens over the past year, took his own life after relentless cyberbullying by trolls who accused him of trying to profit financially from his biological family.

Hangzhou-based counselor Xie Lin believes the stronger self-consciousness of the current generation of teens contributes to the rise in mental health issues. “They pay more attention to emotions than people our age used to,” Xie, who is in her 30s, tells TWOC. “When I was young, we didn’t know much about depression or anxiety. People would just tell you you’re in a bad mood.” Just this past February, Xie, who has a PhD in psychology, saw 68 patients from elementary schoolers to college students, and estimates around half of them are struggling with issues of mental well-being due to internet addiction, study fatigue, school bullying, and family conflicts.

Stigma surrounding mental illnesses sets barriers to teenagers seeking treatment and rehabilitation. “It was weird, as others didn’t have the same experience,” says Liu Hua, now a 21-year-old college student in Guangdong province, on the experience of telling others that she has heard voices since 2017. Liu began sharing her experience on social media platform Xiaohongshu last August to encourage others who suffer from similar symptoms to speak out, and says she received a comment from a follower who claimed that she was “too young” to be unhappy. “We are not this way on purpose, nor are we abnormal,” she says. “Some people say it’s because there’s something ‘dark’ about you psychologically that you are this way.”

Zhou Rui, a 19-year-old high school student from Shaanxi province who has suffered from severe depression due to academic pressure since 2020, tells TWOC that some of her teachers don’t see teen depression as real. “They don’t think kids can get depressed, and if you are diagnosed with depression, they will give suggestions like going for a trip with your parents,” says Zhou.

Parents’ all-consuming focus on academic achievement often leads them to overlook their children’s mental struggles. In 2019, Liu decided to suspend her studies for a year, but faced resistance from her parents at first. “They thought I was trying to escape studying and they were not sure if I could go back to school after a whole year away,” recalls Liu. Yu Nian had a similar experience when she had to take frequent time off to escape from her bully in middle school. “Every time I asked for leave I would have a big fight with my parents. They thought I was too lazy to go to school and was using my illness as an excuse,” she says.

Xie, the psychologist, says it’s not uncommon for parents to view their children’s struggles as signs of laziness or weakness, rather than mental health issues. “This February, the father of a patient asked me, ‘We don’t want to go to work, but we still have to work. Why kids can’t get over their difficulties to go to school?’” she tells TWOC.

Some parents even take extreme actions to “correct” their children’s behavior, like removing the door to their bedroom or restricting their internet access. “We tried to convince one parent that if you had a severe bone fracture, then you may have to lie in bed for three months; it’s the same for a mental illness,” says Xie. “But the parent just responded, ‘I’ve seen people with fractures still going to school on crutches.’”

Li Hong, the 46-year-old mother of a girl who had depression, found it hard to accept her formerly high-achieving daughter sleeping at home for two whole months in 2020. Li herself lost weight and had trouble sleeping after her daughter’s diagnosis, and blamed herself for not being patient enough with the girl. She feels that the pain of parents is neglected in conversations about teen mental health, telling TWOC about a WeChat group of over 200 parents who shared their experiences dealing with their depressed kids. “Some parents even became depressed during the whole treatment process.”

Aversion to medicine also drives some parts of the crisis. In Hangzhou, Zhejiang province, it was reported that a mother replaced her daughter’s anti-depression medication with vitamins as she thought it affected her daughter’s exam performance. Xie blamed the unwillingness to take medication on the demonization of side effects online. “Overall, the side effects of anti-depression medication are not strong, especially for teenagers, and this kind of medication needs to be taken for the long term,” she says. “Some people are quite willing to take medication at first, but stop as soon as they see some [positive] effects.”

The lack of competent specialists also hinders students from seeking help. A 2021 report from Chinese media outlet Huxiu noted that there are only 46 psychiatrists for every 10 million people in China, while in the US the ratio is 1 to 1,000—China is facing a severe shortage of 1.3 million psychiatrists. As a previous TWOC investigation found, school counselors in elementary and middle schools are often just psychology teachers rather than specialists in working with children and teens. Some may even be teachers in other disciplines who have been asked to counsel students part-time.

In Zhou Rui’s high school, students have lectures on mental health only twice a semester, but for a long time, she didn’t know where the counselor’s office was, and says the door was always closed. Even when they’re available, school counseling services may fail to meet students’ needs. Counseling centers at secondary schools often focus on ideological education (a part of the curriculum in Chinese schools focusing on patriotic and political education) and “correcting” students’ way of thinking rather than supporting their emotional needs. Counselors wary of taking responsibility for student suicides may report their situation to teachers, in violation of students’ privacy, or even encourage them to drop out to minimize the risk to the school.

Liu Hua’s parents warned her never to tell her teachers about her condition, afraid that it would cause them to treat her differently. These worries finally came true when Liu wanted to transfer to another school, and her new teachers asked why she left her previous school. “I told them the truth, and you could see them hesitate a little. They didn’t want me to come to their school as they were afraid I’d do something to myself.”

For students with severe conditions like Zhou, psychological services like counseling and medical prescriptions can cost thousands of yuan a month, as they are not always covered under the national health insurance scheme. Some teens may need continuous treatment for years.

To address the long-standing mental health crisis among teenagers, the National Health Commission rolled out a controversial policy in 2020 adding an assessment for depression in the annual health examination taken by students in high school and universities. This raised public concerns about whether the exam infringed on students’ privacy and whether schools were equipped to offer counseling services. In 2021, the Ministry of Education started an online platform for elementary and secondary school students with online classes focused on psychological education.

At this year’s “Two Sessions,” the political meetings of China’s top legislative bodies, representative Ma Jun, associate dean of the Luoyang Institute of Science and Technology, suggested that mental health treatment and counseling services for students be covered under the national health insurance, which can reduce the financial burden of many students and their families.

Last year, Xie’s hospital worked with secondary schools and communities across the country to offer online lectures on various topics like how parents and educators could better communicate with kids. They ended up attracting over 400 participants. “Depressed teenagers may not need treatment. I think they just need someone to understand them and be there for them during the darkest period of their lives,” she says. “It doesn’t need to be a professional counselor, or therapist. Family members, friends, and teachers can also play the role.”

After years of treatment, Liu now has a better understanding of what she was going through. “My entire youth was in pursuit of being the best. I thought I should be praised, that I should be encouraged. But what does being the best truly mean? Now, I’m no longer so keen on getting others’ approval. I’m no longer keen to make myself ‘good,’” she tells TWOC.

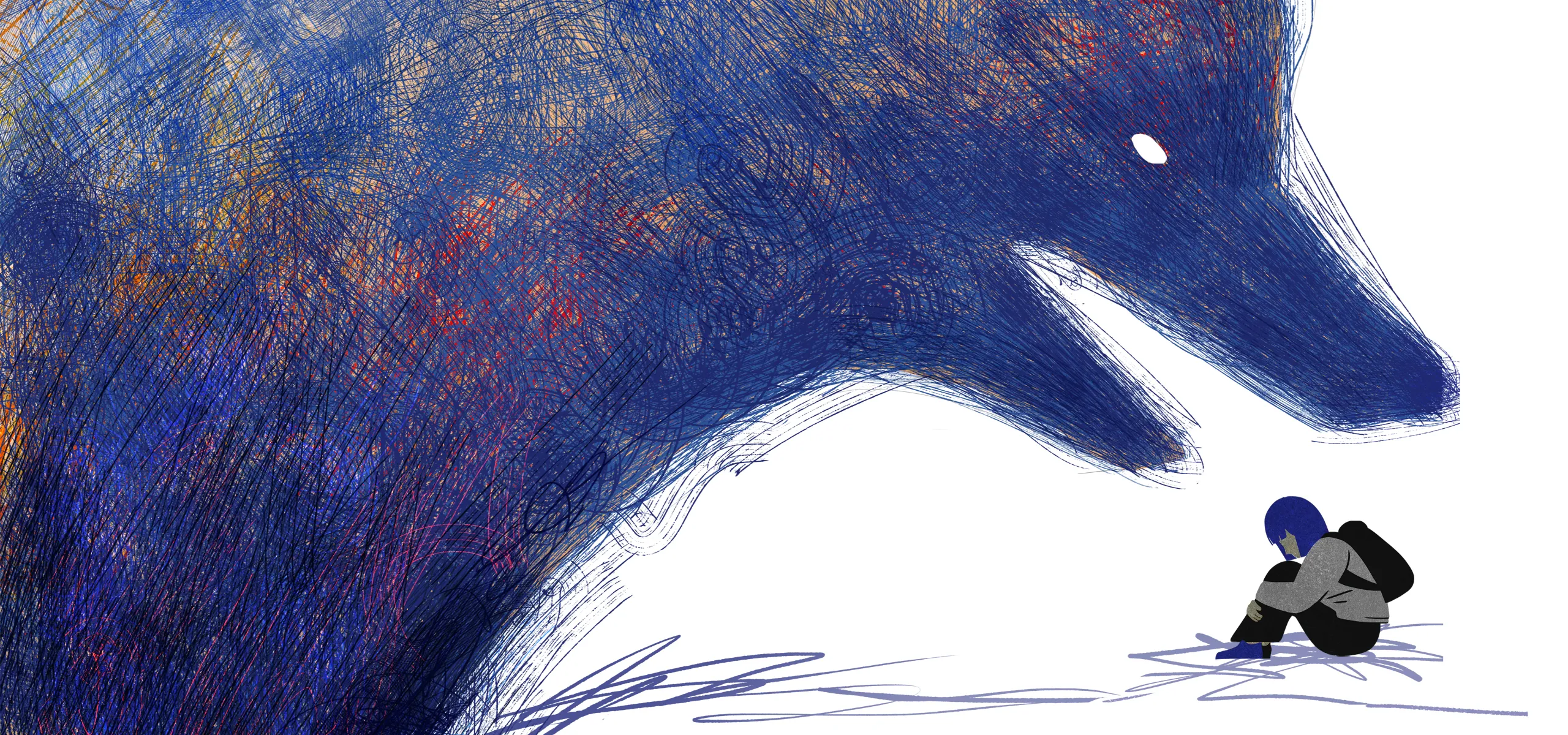

Zhou is also beginning to come to terms with her illness. “Depression is like a black dog which is always lurking behind your back,” she says. “I won’t feel it when I’m ok; I’ll even forget about it. But it comes back whenever I’m feeling down....now, though, I know the feeling won’t last forever.”

For Li, the parent, the hardest part was letting go of her expectations and focusing on her daughter. “I found it hard to accept that such a disciplined, ‘excellent’ kid was suddenly depressed...but what’s the use of me not accepting it? What problem does that solve? Only when you put your child first can you be in the right mindset as a parent, and create a positive environment for your kid’s recovery,” she wrote in 2021 on Xiaohongshu. “There are no perfect kids.”

The names of patients and parents have been changed in this story.

Illustrations by Wang Siqi

“You’re Just Bored”: China’s Depressed Teens Struggle for Understanding and Treatment is a story from our issue, “After the Factory.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.